What am I?

Answer on Monday!

A little more than a year ago I posted a Friday quiz based on a failing Cornus kousa.The answer explained that our landscape has, in part, a perched water table that effectively rotted most of the roots of this poor tree over several years. Last spring we moved it to a different section of our landscape where we know the drainage is better, and I’ve been monitoring its recovery since that time.

Cornus kousa leaves in 2007

Cornus kousa leaves in 2011

We were gratified to see that the leaves this year are significantly larger than those of previous years. This tells us that root function has resumed, providing enough turgor pressure to expand the leaves to normal size. It was especially helpful that we had one of the rainiest springs on record.

Take home lesson: if a tree or shrub is failing in its current location, it’s worth digging up to see what’s going on. Bad soil conditions? Move it to a better location. Bad roots? Time to hone your root pruning skills. But wait until fall to do this. Transplanting this time of year is the most difficult for plants because of the increased water demands of warmer temperatures and expanding leaves.

Today I was reading a review of Amy Stewart’s new book Wicked Bugs and noticed the glee with which the reviewer noted that stings of various insects have been rated on a four point scale. Having read Amy’s book I can wholeheartedly recommend it, but in terms of the stings I thought, what the heck? Let’s see if I can impart some glee to our readers by taking a look at the pain that stings cause (I think it’s kind of like highbrow slap-stick). So here is a brief review of sting science over the years.

First of all, scientists have known for some time that the pain of an insect (or spider) sting is not necessarily correlated with the amount of damage which the sting causes, so scales that have been used to assess the pain of insect stings do not necessarily correlate with the amount of damage done by the sting. The stinging critter is not actually trying to kill the person which it stings (though stings may certainly kill smaller critters), rather, it’s trying to keep them away from itself and its family.

The first person in modern history to actually go to some trouble to figure out how badly a sting could hurt you was William Baerg who, from what I can tell, was dared by a colleague to get himself bitten by a black widow around 1923. He did so, but since the bite didn’t hurt too badly he had the spider bite him again the next day. After this second bite he recorded his reactions – including difficulty in breathing and talking. Apparently a masochist, Baerg continued to allow himself to be stung by scorpions, centipedes, and tarantulas — supposedly in the name of science. And here I’ve gotta say that, as a scientist, you need to set some limits. Actually the stings must not have affected Baerg too badly – he lived from 1885 to 1980.

Following in the footsteps of Dr Baerg, another scientist, Justin Schmidt, has been sting by a tremendous variety of venomous insects (I’ve heard that it’s over 100 different species) and has actually developed a scale to sort out which hurts the worst. The scale runs from 1-4 with a 4 being “debilitating” and 1 being a “spark”. Apparently he never gets stung on purpose – but dang, you can’t be trying too hard to avoid the stings if you’ve got that many species on your “been there done that” list.

Dr. Schmidt published his first paper on the painfulness of stings in the early 1980s. His work was soon followed by a paper published by Christopher Starr. The name of this paper was “A simple pain scale for field comparison of Hymenopteran stings”. This paper includes a list of insects and the level of pain which they cause with their sting – basically following Schmidt’s work – but Starr makes sure that he has at least two data points before he lists the pain which the insect causes. He also makes a point of noting when the insect was induced to sting instead of having the sting just happen. According to his chart he was stung by 34 (if I counted right) different insects, and of those stings only 6 were induced. Obviously this guy didn’t take his work as seriously as Baerg or Schmidt!

Most of the stings that we’re accustomed to – bees and wasps – are around a 2. There are a few at a level of 4 – probably the most notable is the bullet ant.

Starr ends the conclusion section of the article by listing 6 important rules for grading stings – I found them fascinating – so here they are:

Cape San Blas

mullet and bass

cheap sunglass

sand flea and crabgrass

beachy landmass*

Had big, relaxing fun last week in the greater Port St. Joe/Cape San Blas/Apalachicola region of the Florida panhandle (billed as the "Forgotten Coast" or more locally "Florida’s Last Stand"). The bays are filled with fishies, the gulf is turquoise and rimmed with soft white sand. Highly under-developed, it’s truly paradise for anyone who likes to boat, fish, kayak, and run with your hounds on empty, wide, dog-friendly beaches. I’ve got fodder for a couple of posts, but will postpone the flora/landscape observations until next week.

The news of the awful outbreak of a particularly virulent and dangerous strain of Escherichia coli in Europe coincided with my own mid-vacation, not-so-pleasant experience. Twenty-four hours of bed-bound, trash-can-gripping, don’t stray far from bathroom non-activity while paying for a beach house and boat rental gave me some time to think deep thoughts about food safety. Salad, meat, seafood, and cream sauces were all involved. I could have ingested one of any number of sweat-and-barf-inducing microorganisms. Being off food and drink for another couple of days wasn’t ideal either. I didn’t go on vacation intending to detox (rather, "to tox"). But at least I was up and about. Renal failure and death takes the E. coli strain O104 to a whole ‘nother level.

In digging for a bit more information, the usual safe food handling advice has been trotted out in regards to this vicious beast; wash, peel, cook, etc. But a microbiologist at a Scottish agricultural research center (The James Hutton Institute) has noted there are strains of E. coli “associated with plants, not animals.” Dr. Nicola Holden says that the bacteria “are not simply sitting on the surface of the plants and are particularly difficult to remove post-harvest.” She goes on to state that these particular bacteria colonize the root system and then “have the opportunity to move to the edible foliage or fruits.” Yes, E. coli is a motile organism; that’s one way to get from the soil to your salad, but there is evidence it can invade the tissue and move within the plant; no amount of peeling or washing will help. Dr. Jeff LeJeune’s lab at Ohio State was taking a look at this several years ago, especially how E.coli can enter through points of damage from mechanical injury or plant pathogens. Haven’t had a chance to dig any deeper, but will be having a chat with a friend from our Food Science and Technology Department to find out more.

*apologies to the Car Talk guys, but I always wanted to do that.

I just got back from a 9 hour overseas flight, just in time to post the answer to last week’s quiz. So now you know…I wasn’t in the states. More on that later.

As many of you guessed, this is a fig tree (Ficus spp.) of some sort. I have horrendous taxonomic abilities anyway, but will cover my ignorance with the excuses that the tree wasn’t in flower, nor were there any signs in any of the little parks identifying the tree. So we can continue to speculate on what species this is. I do know it’s quite an old specimen, and that there are some Ficus native to the region, but past that I’m clueless as to whether this really is a native species or not.

And where was this huge tree? In Alicante, Spain, where I spent a few days visiting my daughter who’s studying there this semester. (Non-scientific aside: I would go back there in a heartbeat. If you are looking for a Mediterranean tourist destination that isn’t overrun with Americans, this is the place to go.)

Finally, these cool wavy woody structures are buttress roots, as Jospeh, Shawn, Rotem and Deb all pointed out. They have both a structural and storage function: like all woody roots they store carbohydrates, but the over-developed flare helps support the tree in thin soils (like here) or in wet, low-oxygen soils (like those where mangroves grow). In both cases roots can’t reach far enough below ground to stabilize the trunk, so the buttressing serves that function.

@Rotem also noted that branches can root and support the tree. While the buttress roots in the original photo arose from root tissue, you can see examples of the rooted branches in the photo above.

And I do love the less-than-serious answers some of you kindly provided for our amusement. Fred’s "rumble strips for drunks" was particularly apropos, since my last night there was one big street party after Barcelona beat Manchester United in the Champions League soccer match. My daughter and I ended up in our hotel elevator at 8 am the next morning with a fan with no pants. We did not ask.

I’m out of town this week, and taking lots of plant pictures. Here’s an interesting tree, quite common in the city where I’m staying:

Question 1: What kind of tree is this? (Genus is good enough – species might be hard to tell.)

Question 2: In what geographical region might I be staying? (The tree is native as far as I know.)

Question 3: What are these woody structures called, and what function do they play?

Answers next week!

Paul, Joseph, Kandi and Derek are all, apparently, Puya fanciers. But! It’s not P. alpestris, but P. berteroana – a species whose flowers are more turquoise than sapphire:

Yeah, Kandi, check out those spines! Even taking pictures is deadly!

And Paul and Joseph were correct – the long green structures are sterile (they bear no flowers) and serve as bird perches. The nectar almost runs out of these flowers, and as the birds get a sugar fix their heads are covered in pollen.

Thanks to Paul Licht, Berkeley Botanical Garden Director, for my short but fabulous tour that included these beauties.

Like many readers of this blog, I’m like a kid in a candy store where plants are sold. I try to justify the extra cost of a large annual pot instead of a scrawny 4-pack, or I imagine I’ll find room for that lime green Heuchera and my wife will learn to love it. But unless I keep my blinders on and stick to the shopping list, I’ll probably leave with a fertilizer. This year, I’ve purchased 12-0-0, 5-6-6, sulfur, and some 5-1-1 liquid. Those go with my 6-9-0, 11-2-2, 9-0-5, 2-3-1, and 4-6-4. I can explain why I ‘need’ each one. I have a decent idea what my soil is like because I’ve had it tested (though I’m due for another test). But I’ve always questioned how those bags of fertilizer can know exactly what my garden needs. The rates listed on the bag imply they’re universal under all circumstances and will give great results if the directions are followed. Is that true? And at what cost?

For example, 2 of the bags are listed as ‘lawn’ fertilizers (the veggie garden doesn’t care about that though). But if I apply these to my lawn at the rate listed and 4 times per year, I’m adding 3-4 pounds of nitrogen per 1000 ft2. That’s a reasonable rate if I irrigate and bag my clippings, but I don’t do either. Therefore, I only need ~1 pound of nitrogen, not 3 or 4 (see this publication for more info). I just saved myself some money by disobeying the bag. That extra nitrogen isn’t useful for making MY lawn healthy.

One of my fertilizers is labeled ‘tomato’. If I do exactly as the bag tells me for tomatoes, I would be applying the equivalent of 400 pounds of nitrogen and almost 500 pounds of phosphate per acre. So what? Well if I look at a guide for how to grow tomatoes commercially, I’d notice that the recommended nitrogen rate is 100 to 120 pounds per acre, and phosphate is 0 to 240 pounds per acre. Yes, those are commercial guidelines, but they shouldn’t be too far off from garden recommendations. And of course, recommendations should always be based on soil tests. But 4 times the N and 2 to infinitely more times the amount of phosphate than is required? That’s likely a waste of money at least. And yes, those recommended guidelines are real: you CAN grow food without adding phosphate or potassium-containing fertilizers. If the plants you’re growing don’t need much and your soil has plenty, you don’t need to add any.

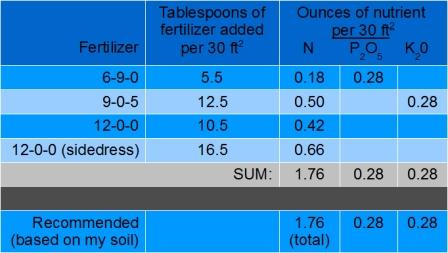

Say I’ve got an acre of onions (Fig. 1; not quite an acre). One of the bags of fertilizers, were I to follow its instructions for fertilizing ‘vegetables’, tells me that I should add 100 pounds of nitrogen and 120 pounds of phosphate and potash at planting (per acre), followed by half that partway through the season (next to the row). The commercial production guidelines tell me that the nitrogen rate is similar to what the bag of ‘vegetable’ fertilizer says, but I actually need about 7 times less phosphate and potash (based on my soil test results; I have quite a bit of P and K already in my clay-loam soil). I don’t want to add stuff my soil doesn’t need, so I use my shelf full of bags, a scale for weighing pounds of fertilizer per cup, and some math to come up with a custom fertilizer regime that suits my soil and the onion’s needs (see Table 1, and remember that the numbers are for MY soil, not necessarily yours).

One problem with using extra fertilizer may be in the extra cost (wasting nutrient the plant won’t use), but that depends on what fertilizer it is and how much it costs. Another problem may not be immediately apparent, and that is nutrient deficiencies. Too much phosphorus can cause zinc deficiencies, for example. Excesses of some nutrients can create greater chances for pest and disease problems. One big problem with using too much is the potential for these extra nutrients to go where they shouldn’t be, like in groundwater, rivers, lakes, and streams. And as Jeff has mentioned, phosphorus fertilizers won’t be around (cheaply) forever.

Do the work of figuring out what kind of soil you have and what’s in it, what your fruits and veggies need, and what kinds of fertilizers can do the job for you. Heck, you can even organize your fertilizers based on “cost per pound of nitrogen” to see where the best bang for your nitrogen buck will be. But none of us are THAT obsessed about our fertilizers, right?…. [$ per bag / (pounds per bag * (% nitrogen/100))].

As a reminder, the numbers on your fertilizers are percent nitrogen, phosphorous (as ‘phosphate’, P2O5), and potassium (as ‘potash’, K2O). One cup is 16 tablespoons, and an acre is has length of one furlong (660 feet) and width of one chain (66 feet), or 43,560 square feet. Side rant: metric rocks.

I was driving around town recently and saw a tree service crew clearing up some storm damaged trees. Because of my line of work I usually do a little rubber-necking and try to assess why type of tree came down and what issues may have preceded it’s demise. In this case, however, I was struck not by the trees but by the tree crew. What I saw left me speechless. Well, here, see for yourself…

No eye protection. No hearing protection. No sign of a hardhat, face-shield, or chaps by the chainsaw. No personal protective equipment anywhere as near as I could tell. Of course the photo illustrates a lot of what’s wrong with the landscape and tree service industry. Economists tell us that this industry has a ‘low barrier to entry’; in other words any one with a chain saw and a pickup truck can put an ad in the classifieds and call themselves a tree service. As a consumer, you may not care if the employer makes their employees where personal protective equipment (PPE). But if they don’t care about their employees’ safety, what else don’t they care about?

Periodically I’ll write an article for a newspaper or other media on selecting an arborist. I always make the point that you get what you pay for and urge consumers to compare bids and companies carefully. Truly professional tree services have to cover the cost of hiring and retaining quality employees, worker training, proper equipment (including PPE), and insurance. If you skip over those things, like Fly-by-night tree service here, it’s probably not too hard to come out with the low bid.

The university’s server was down for scheduled maintenance over the weekend and I missed getting this posted. So you have until next Friday to consider this interesting flower from the Berkeley Botanical Gardens:

What is this plant?

And what is the function of these long, green horizontal structures?

Have fun