We have seen many high-profile examples of insect invasions, and as gardeners, we have probably come across some of these species in our very own landscapes and experienced their impacts first-hand.

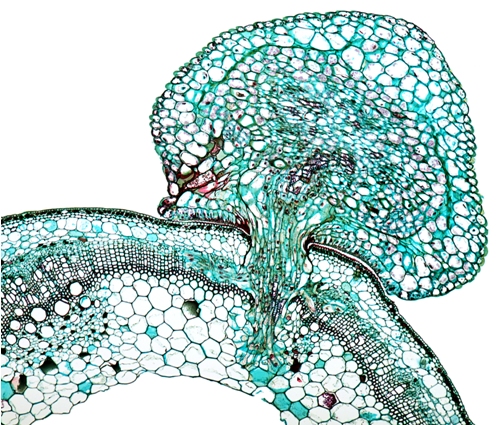

If you live in the Eastern part of the United States, you have probably already heard about one of these invasive insect species that is currently wreaking havoc. The Spotted Lanternfly (SLF), Lycorma delicatula, is a 1 inch long planthopper native to China, and has since spread to Japan, South Korea, and the United States. This is a piercing/sucking insect (Order: Hemiptera) that feeds on the phloem of plants and excretes a sweet and sticky product called honeydew. This feeding damage, especially in large populations, can impact the health of certain plant species. Not to mention the nuisance potential, as any objects under infestations of this insect will find themselves coated in a sticky layer of honeydew.

It was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014, and can now be found in several surrounding states including Delaware, Indiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia, although most states are considered at risk for SLF invasion. Although the insect itself can’t fly long distances, it can be easily spread by moving infested materials and through their egg masses which look fairly nondescript (like a small smear of mud). Several states are currently quarantining this pest, so follow regulatory guidelines by visiting your state’s department of agriculture. Inspect your vehicles and personal effects for the insects and their egg masses (and scrape them off/squish them) especially if you are traveling through these quarantine areas to prevent spreading them to new locations.

This insect has over 100 potential host species, and this wide dietary breadth adds unique challenges to this insect’s pest potential. Its preferred host plant is another invasive species: Tree of Heaven (Ailantis altissima), which is currently widespread in the US and parts of Canada.

SLF can also be problematic for some important fruit crops such as grapes, where it has the potential to reduce fruit yield, impact fruit quality, and potentially reduce hardiness and winter survival. There are also other economically important trees that this insect feeds on, including apple, maple, black walnut, birch, willow, etc.. Feeding damage can stress plants leaving them susceptible to other pests and diseases. If this pest continues to spread it could have significant impacts on the US grape, horticulture, and forestry industries.

Invasive insect species can also have significant impacts on natural ecosystems, and can tip the balance of a well-functioning food web. Adding a pest that often has very few adapted natural enemies, and especially those that can reduce the availability of an important food and shelter source for other native organisms can result in cascading ecological effects that can be difficult to understand and manage.

It is important to stay vigilant in keeping an eye out for invasive species such as Spotted Lanternfly, so if you see this insect outside of a currently quarantined area, before you squish the bug; take note of where you spotted it and report it!

State-specific reporting guidelines for Spotted Lanternfly can be found here: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungry-pests/the-threat/spotted-lanternfly/

If you are curious about other current/potential invasive pests in the US (and state specific guidelines for invasive pests) visit: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/resources/pests-diseases/hungry-pests/pest-tracker

To learn more about this insect, visit: https://ag.umass.edu/landscape/fact-sheets/spotted-lanternfly

You can also reach out for more information to your state department of agriculture, or your local and regional extension offices.