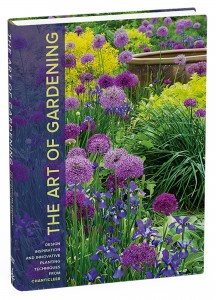

Ornamental onions are hot patooties. From big, bold, purple globes to small pink half-moons, there is no end to ornamental onion-y goodness out there with 30+ species and cultivars in the trade. There’s no substitute for ornamental onions in regards to architectural drama – the perfect geometric foil to wispy grasses, floral spikes, and umpteen daisy-thingies. The seed heads from the sturdier species will persist and add interest to autumn and winter perennialscapes (not sure if that’s a word).

All are members of the Allium genus, just like those onions sprouting in your kitchen counter veg basket – hence the deer- and small mammal- resistance factor. However…there are some issues.

- Can be short-lived. I have first-hand experience with this – plant, enjoy for a year or two, then…where did they go?

- Bloom time is rather vaguely defined. Most catalogs list “early summer” or “late spring” for most cultivars. But if you want continuous purple orbs, what’s the order of bloom?

- Can be expensive. Bulbs for some of the mammoth “softball” sizes will set you back $5-$7 each (the bulbs themselves are huge). This is of particular concern due to the first item.

- Foliage failure. For some of the largest species and cultivars, the foliage starts to die back around (or even before) bloom time. Not a lot of time to put the necessary energy back into that big honkin’ bulb.

We already have a multi-year lily perennialization trial going in conjunction with Cornell and some other institutions. I thought I might try the same thing with Allium.

Unfortunately, I had this bright idea in November – well into the bulb-ordering season. I tried to compile as complete an inventory as I could, ordering from several vendors. Ended up with 28 species and cultivars – as much as the space prepared (check out that nice soil!) could hold, at our urban horticulture center near campus (Virginia Tech is in Blacksburg, USDA Zone 6, about 2000′). We put five or seven bulbs (depending on size) in each plot, and replicated the whole thing three times.

We’ll take data over the next three years on time of emergence, bloom time and duration, foliage duration (have a nifty chlorophyll meter that can help quantify that), some growth measurements, and perennial tendencies (or not). My hope is to end up with a really specific chronology of bloom times plus life expectancy. Yes, this was just a patented Holly wild hair; luckily I had some general funds to cover it. But I do think our little onion project will be of interest to more than a few folks, whether professional landscape designers or home gardeners. I know I’m excited to see the results ($30 for five bulbs – yeek)!