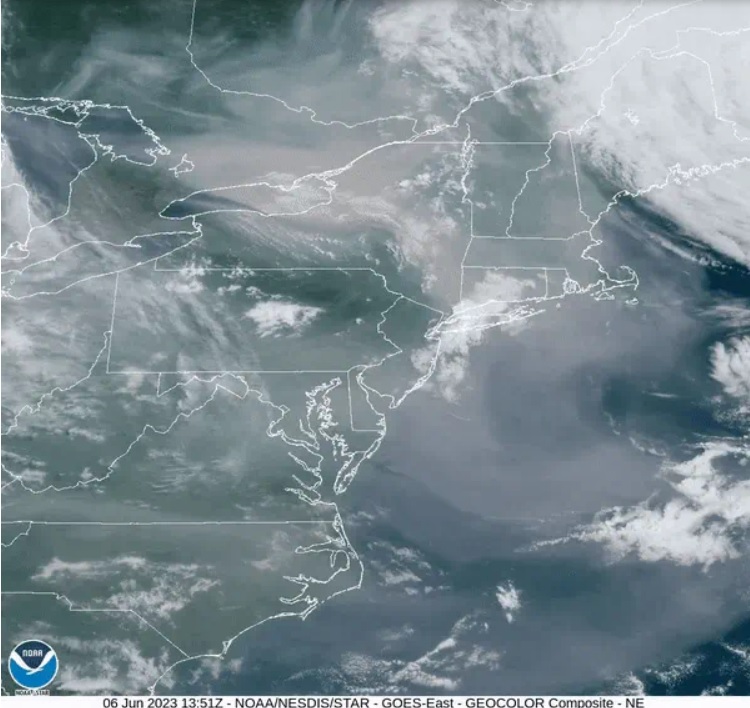

Over the last month, I have seen many stories related to smoke from Canadian wildfires drifting down into the eastern United States, causing muted sunsets as well as terrible air quality. Even my mom up in Michigan told me how bad the air is up there this week and friends in Wisconsin have told me that they can’t go outside without donning N95 masks to cut down on breathing in all the smoke particles. Of course, our readers in the western U. S. may be rolling their eyes since they have gone through severe wildfire seasons in past years with little attention from the eastern press, and poor air quality from wildfires and pollution is also a frequent problem in other parts of the world. But since it is in the news, I thought I would address aerosols and their impact on the atmosphere, human health, and our gardens.

What is an aerosol?

Aerosols are very small particles that float in the atmosphere. They can be from natural sources like salt from breaking ocean waves or pollen from blooming plants or can produced by humans through burning coal, construction, or poor agricultural practices. Saharan dust, volatile organic compounds emitted by trees, wildfire smoke, and volcanic ash can all add to the dust burden in the atmosphere. Some aerosols attract water vapor, causing them to expand in size and reducing the visibility of the atmosphere even more than the particles alone. Aerosols can be toxic, too, and areas with a lot of atmospheric pollution can cause severe problems for vulnerable people and pets when aerosols get deep into lungs.

Impacts depend on where they are in the atmosphere

The impacts that aerosols have on humans and the environment near the ground depends on how high up the aerosols are concentrated. If the particles were lifted above the surface due to the heat from burning forests or trash, the main effects that the aerosols might have are optical, reducing the amount of incoming sunlight but not significantly affecting the air we breathe near the ground. Some acidic particles that attract water vapor might also contribute to acid rain that falls to earth. But if the dirty air is mixed down to the ground or is produced locally, the aerosols can cause significant issues for human and animal health because of their irritating effects on lungs and sometimes skin and eyes. They can also provide hazards to transportation if visibility gets too low. Acidic particles can also cause damage to plant tissues or change the pH of the soil if they affect an area over a long time period.

How do aerosols affect climate?

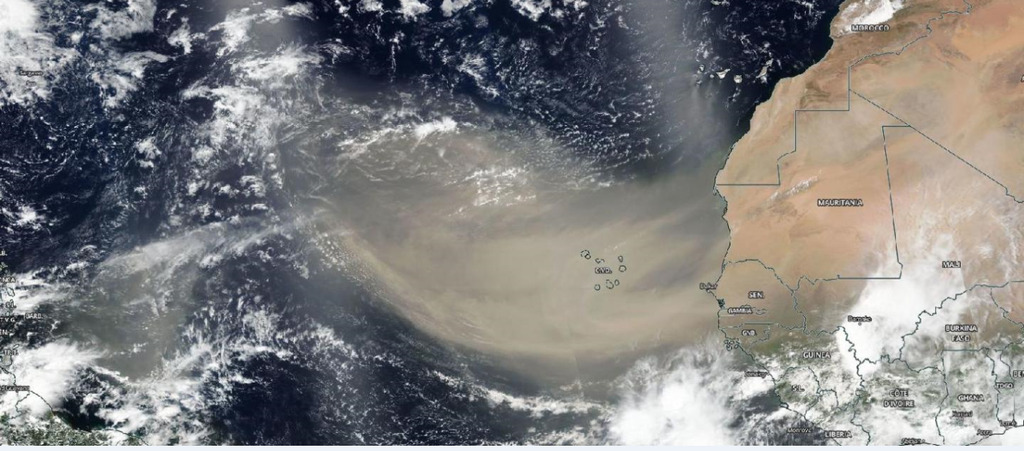

Aerosols affect climate by reducing incoming solar radiation. Volcanic ash and sulfuric acid droplets from volcanic eruptions can cut enough sunlight to reduce global temperatures for several years after a large volcanic eruption, especially if they occur in the tropics. This year’s unusually warm Atlantic Ocean temperatures can be linked in part to a lack of the usual plume of Saharan dust blowing off the west coast of Africa, which has allowed more sunlight to warm the surface water. The so-called “warming hole” in the Southeast has been linked to aerosol emissions from power plants upwind in the Midwest and Western U. S., which caused reductions in sunlight over the Southeast until the passage of the Clean Air Act of 1970 reversed that effect. Since then, the temperature in the Southeast has risen in concert with rising temperatures across the rest of the world. Aerosols contribute to the development of clouds, too, and that has the potential for affecting climate at larger spatial scales.

How do aerosols affect health?

Aerosols affect human and animal health when they are inhaled into the lungs, irritating tissues and causing swelling and producing fluid as the lungs try to clear the aerosols out. According to estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO), particle pollution contributes to approximately 7 million premature deaths each year, making it one of the leading causes of worldwide mortality. Fine particles that are smaller than 2.5 micrometers (called PM2.5) are the most damaging because they are so small that they can make it deep into the lungs where they are deposited on the lung tissue. Because of this, gardeners and others who spend a lot of time outside need to be aware of the current air quality measurements and minimize time outside when the air quality is bad. You can find current air quality information in the United States at AirNow. Many state health agencies also post air quality information and the National Weather Service also puts out alerts on days with bad air quality. When the plumes of smoke from the Canadian wildfires moved over the Midwest and the Northeast, some U.S. cities had the worst air quality of any metropolitan areas in the world while the smoke was present.

How do aerosols affect gardens?

Aerosols have several impacts on plants and gardens. Aerosols provide benefits for gardeners since clouds and rain form from water that is collected into water droplets on aerosol particles known as Cloud Condensation Nuclei (CCN). No doubt if you collect rain or snow water, you have seen the dirt that remains after the water is gone. But aerosols also have detrimental effects. Aerosols aloft can reduce incoming sunlight, leading to slower plant growth, especially for plants like corn that are sensitive to the amount of sunlight they receive. Aerosols at ground level can cover the plants with a layer of dust that decreases photosynthesis by blocking incoming sunlight and clogging pores. If the aerosols are acidic or contain toxins, they can damage the plants or increase the acidity of the soil, especially over long time periods. In the case of smoke from wildfires, the smoke particles can also affect the taste of grapes or other food products they interact with. Smoke taint on wine grapes, caused by compounds from aerosols that are absorbed by the grapes, can impart an ashy flavor to the wine made from those grapes, making it unsellable, as producers in California and Europe have found in recent years.

If you are experiencing air quality issues in your community, we encourage you to monitor the weather forecasts closely and stay inside when the aerosol count gets too high, especially if you have asthma or other lung conditions that may be made worse by poor air quality. If you have noticed other impacts of the wildfire smoke or other air quality issues on your garden plants, please feel free to share them in the comments.