I’ve written before about my time as a trial judge for the All-America Selections program, which I did during my seven years with Nebraska Extension. I happened upon the opportunity to be a judge by accident, but really came to relish my time and the work that the organization does.

You see, All-America Selections started in 1932 as a way to actually certify the claims that newly-introduced plants were actually better than ones already available. Previously it was sort of the wild-west of claims made by everyone who had a garden catalog or wrote a garden publication. There was no way to level the playing field and certify these claims until W. Ray Hastings, the president of the Southern Seedsman Association, established the All-America Selections trial program. As a non-profit and now part of the National Garden Bureau, the organization and its volunteer judges can serve as impartial arbiters of the superiority of newly-introduced plants.

This is especially important in this day and age of spurious claims and piles of misinformation on the web. The organization uses a research-based approach in determining high-quality plants with replicated trials all across the country. Plants have to perform well in all regions of the country to be a winner. Sometimes if a plant does well in one area but not others, it will be considered a regional winner.

Ninety-one years later the organization still serves as the gold standard for performance in home garden plants. Judges have a track record of picking plants that are favored even decades after they are introduced. The ‘Celebrity’ tomato, winner from the class of 1984, has probably been grown by almost everyone who grows tomatoes and can be found in almost every garden catalog or seed rack. ‘Bright Lights’ Swiss Chard, class of 1996, is also a go-to favorite for almost anyone who grows chard. And while many plant cultivars come and go with trends and company closures, there are still seven cultivars from the first class in 1933 still available for home gardeners to purchase through retailers: Tomato ‘Pritchard’, Spinach ‘Giant Nobel’, Pansy ‘ Dwarf Swiss Giants’, Nasturtium ‘Golden Gleam’, Carrot ‘Imperator’, Canterbury Tale ‘Annual Mixed’, and Cantaloupe ‘Honey Rock’. You can check out their profiles on the AAS website to see where to buy them.

2024 Winners

So far there have been 10 winners announced for the 2024 garden season. It unlikely that any more will be introduced at this point, but they often aren’t announced until they are ready to go to market so there’s always a chance. I served as a judge for the edible crops (vegetables, fruits, herbs) for both in-ground and container trials so I’ll start with the edible winners. Then I’ll also share info on the ornamental winners. You can always find more information, including which seed and plant suppliers/retailers carry the plants, at the AAS website.

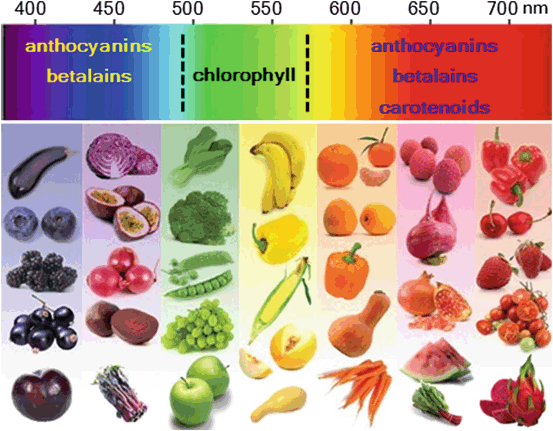

Broccoli Purple Magic F1

A striking purple broccoli with tight growth habit. Judges noted it for its great broccoli flavor that was sweeter and more tender than the green broccolis to which it was compared. It was also noted for its heat and stress tolerance.

Broccoli Skytree F1

This broccoli’s long stalks set it apart. They make the compact heads easy to harvest. It is also noted that the stalks themselves are tender, sweet, and flavorful so they should be eaten as well. It is noted as being uniform and early maturing. Skytree was a regional winner in the West and Northwest. Container suitable.

Pepper Red Impact F1

This is a Lamuyo pepper which is a Spanish pepper noted for exceptional sweetness. It is sweeter than your standard bell pepper. The fruits are huge – nearly 8” long and double the size of standard bell peppers. We noted that they were delicious and sweet, even when green.

Celosia Burning Embers

A beautiful and long-lasting celosia in the garden. It is noted for its bronze leaves with pink veins and bright flowers. It is well-branched, heat and drought tolerant, and long-lasting in the garden. It lasted well past other types trialed. Container suitable.

Geranium Big EEZE Pink Batik

This geranium was noted for its long-lasting flowers and large flower heads. The prolific and large flower heads have a unique pink and white mosaic design. Judges also noted that it was very sun and heat tolerant. Container suitable.

Impatiens Interspecific Solarscape ® Pink Jewel F1

Noted for the bright pink flowers with an opalescent sheen, these flowers lasted well through the season. These plants are sun tolerant and also noted as being resistant to impatient downy mildew, which has basically made it almost impossible to grow (or buy) impatiens lately. Container suitable.

Marigold Siam Gold F1

This large-flowered marigold was noted for season-long performance. It was also noted that the plants didn’t need staking, even though they were tall and had large flowers making them top-heavy. Container suitable.

Petchoa Enviva™ Pink

You might be asking yourself the same question I did – “what the hell is a petchoa?” And the answer is great – it is a hybrid cross between an Petunia and a Calibrachoa, often called Million bells. The result is a beautiful, mounding plant that is covered with large, beautiful pink iridescent flowers with yellow throats. The judges noted that plants performed well all summer, even in extreme conditions. Container suitable.

Petunia Sure Shot ™ White

The judges noted that this petunia performed like a powerhouse all season long, including extreme summer heat and weather. Most notably, the flowers kept their snow-white flowers all season, whereas many white flowers fade or get blemished quickly after blooming. Regional winner from the West, Northwest, and Great Lakes regions. Container suitable.

Verbena Sweetheart Kisses

This blend of verbena has pinks, roses, reds, and whites that were super attractive to bees and other pollinators. Judges also noted the fine foliage, which isn’t like standard verbena foliage. The plants performed well all season long, even in heat and drought. Container suitable.

Wrapping it up

Finding that AAS seal is a great way to assure that you’re buying high performing plants for your garden. I truly did enjoy my time as a judge, even though my trials were often “if it lives through this, it definitely deserves an award” type of gardening. Now that I’ve left Extension, I’ll no longer serve as an official judge, but I still plan to volunteer to help the Extension office and serve as an “ambassador” for the AAS program. I’m glad they’ll let me stick around!

“Certified organic” means that the producers practices have been certified to meet the requirements laid down by a certifying agency. A certifying agency could be a non-profit or a state department of agriculture. The requirements and practices vary from entity to entity.

“Certified organic” means that the producers practices have been certified to meet the requirements laid down by a certifying agency. A certifying agency could be a non-profit or a state department of agriculture. The requirements and practices vary from entity to entity. “

“