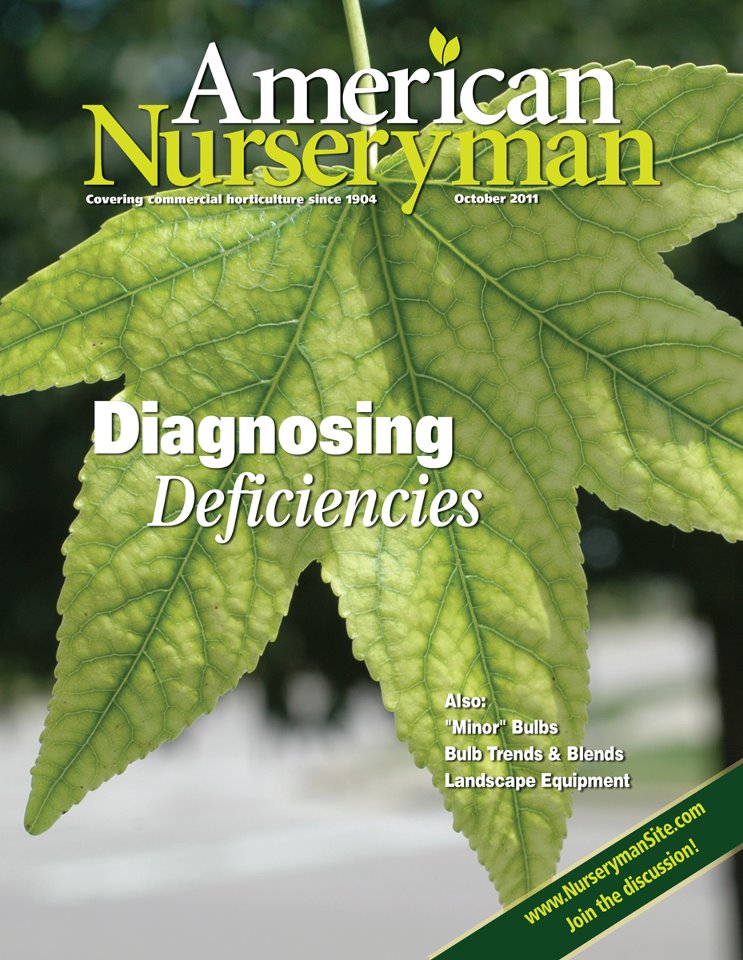

As an Extension Specialist working with nursery and landscape issues, I’m frequently called upon to troubleshoot problems with trees and shrubs in various settings. Sometimes it’s residential or commercial landscapes, sometimes nurseries, sometimes Christmas trees. So naturally I was intrigued when the most recent issue of American Nurseryman featured a cover story on diagnosing nutrient deficiencies in plants. The article was written by Dr. Gary Gao, Extension specialist with Ohio State University. The article http://www.amerinursery.com/article-7428.aspx is good and does a good job on covering the basics. However, the introduction of the article also hit on one of my pet peeves – and what is the Garden Professors for if not to vent on our pet peeves.

The intro states:

"If you have a good understanding of the function of plant essential mineral elements and a familiarity with common symptoms, common mineral nutrient disorders can be diagnosed quite easily."

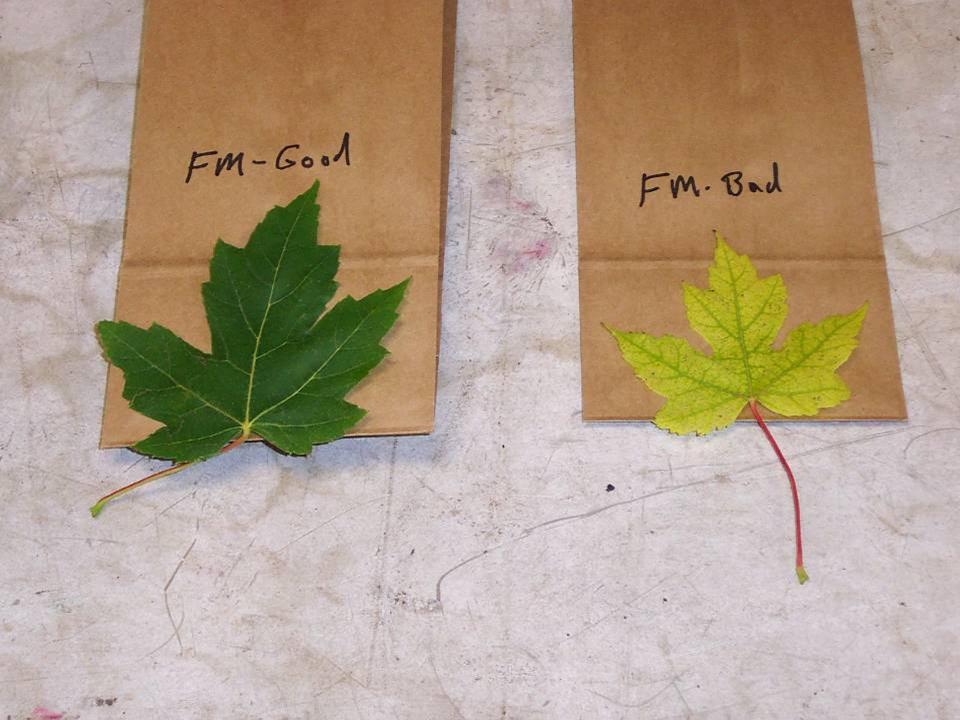

Maybe I’m just trying to justify my own existence, but I find diagnosing nutrient disorders anything but easy. This article and countless extension bulletins and factsheets imply that you can diagnose nutrient problems simply by matching leaves from your tree or shrub to a photograph showing the same symptoms. To which I have three words: Ain’t gonna happen. For the upper Midwest, I can think of exactly two landscape nutrition problems that I would be comfortable diagnosing by visual symptoms; iron chlorosis in pin oak and manganese deficiency in red maple. Beyond those two I would want information from foliar samples and soil tests, as well as some site information before concluding the cause of a plant problem.

The main issue, of course, is that plant problems rarely come gift-wrapped. Nutrient deficiencies (or, rarely, toxicities) are often confounded with other site issues; poor drainage, excessive drainage, too much sun, too much shade, insect damage, diseases, salt exposure. As I’ve said many times, it’s much rarer to find a ‘smoking gun’ than not. Usually it’s process of elimination with a best case scenario where you can compare symptom and foliar analyses of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ plants. But I think we do a disservice to landscape and nursery professionals and homeowners to imply that identifying the cause of a problem is as simple as picking the right suspect out of a line-up.