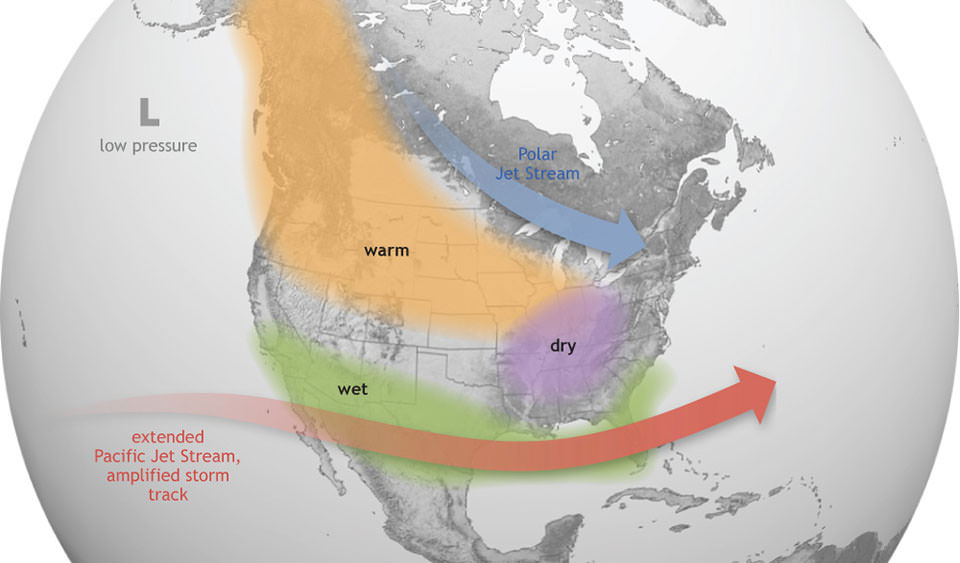

Last April 30, 2022, I wrote a post about what a third year of La Niña meant for gardens. La Niña, you might remember, is an atmosphere/ocean phenomenon driven by unusually cold water in the Eastern Pacific Ocean (EPO) that shifts the jet streams that steer storm systems around the world. In La Niña winters in North America, it is often linked statistically to colder and wetter than normal conditions in northern parts of the United States and north into Canada and warmer and drier conditions in the southern tier of states in the US. Just a couple of weeks ago, NOAA announced that the long La Niña has finally ended and that we are now in a neutral period. In last year’s post, I described the difference between La Niña and the opposite climate phase, El Niño, and how they affect climate conditions around the world. So now you might be wondering how this switch to neutral conditions and then potentially to an El Niño later in the year will affect your gardens in the coming growing season.

Elfen-Krokus (Crocus tommasinianus), AnRo0002, Commons Wikimedia

How good was last year’s forecast?

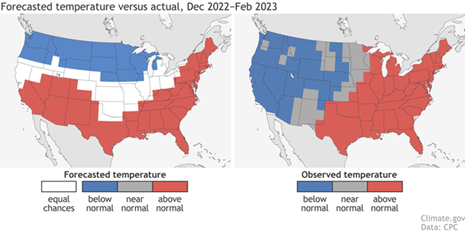

A discussion of how accurate the forecast for last winter was can be found in NOAA’s ENSO blog. As you can read, the temperature forecast was much better than the precipitation forecast (as it usually is). That is not surprising because many causes of rain and snow occur on very small spatial scales from a variety of physical processes that are not always well-captured in our current climate models. You can hear a more detailed discussion of historical ENSO patterns by David Zierden, the Florida State Climatologist, in this 15-minute video for the March 2023 Southeast Climate Monthly Webinar starting at minute 28:35).

As a result of the cold and snowy conditions in northern parts of the country, spring there has been delayed, and my friends in the Upper Midwest have only started to see daffodils and other early spring flowers, while in the Southeast, our azaleas and dogwoods are already in decline about a month earlier than usual (you can track this at the National Phenology Network website we’ve discussed before).

What happens next?

Now that La Niña has ended, we are in neutral conditions. That means it is difficult to predict the climate during the next few months because without La Niña (or El Niño) to give us statistical guidance on what climate to expect, almost anything can happen. The variations in climate in neutral seasons are caused by local variations, other interactions in climate on regional or global scales, and other factors that are not always well understood. In addition, we are in spring, which historically gives us the least trustworthy predictions for the coming seasons due to what is called the “spring predictability barrier.” That means that while we think we are likely to swing into an El Niño in the next few months, the atmosphere might have other ideas and could keep us in neutral conditions for quite a while before we switch to an El Niño.

This year, we are already getting signs in the Eastern Pacific Ocean that a switch to El Niño will come quickly. The water near the coast is already quite warm and the warm pool is starting to stretch out to the west. In other words, El Niño-like conditions are already present in the EPO, but have not lasted long enough yet for an official El Niño to be declared. That usually takes several months of monitoring to make sure this is not just a short-term change.

What do neutral and El Niño conditions mean for the Northern Hemisphere growing season?

Usually, ENSO conditions do not strongly affect the NH summer climate. That is because both La Niña and El Niño are strongest in the winter months and tend to weaken or disappear in the summer. Local conditions including soil moisture variations such as drought, ocean temperature variations, and local weather systems have a much bigger impact on growing season weather than ENSO does in most areas.

However, the ENSO state does have one strong influence. That is in the tropical activity in the Atlantic and Eastern Pacific Oceans. When neutral conditions or La Niña conditions occur, the jet stream aloft is weak and it is easier for tropical waves to develop into tropical storms and hurricanes, so neutral and La Niña seasons tend to be more active and have more named storms. When an El Niño occurs, the jet stream is unusually strong and that keeps tropical waves growing vertically into strong storms, so the number of tropical storms and hurricanes in the Atlantic is usually lower in years when an El Niño is occurring. Of course, it only takes one storm (Hurricane Andrew in 1982 was in an El Niño year) to cause tremendous damage if it hits somewhere vulnerable. In contrast, the storm activity in the EPO increases in El Niño years due to the pool of warm water there.

This year, the likely storm activity may be more tied than usual to the ENSO state. If we see a quick switch to El Niño after just a few months of neutral conditions, the Atlantic may be most active early in the season, while storms later in the season will be suppressed. By comparison, in the western US where some moisture enters the country through EPO storm activity, you may see an increase in thunderstorms that are fed by the water vapor entering the country from the storms in the EPO.

What does this mean for your gardens?

If you live in an area that normally gets rain from Atlantic tropical activity, even if it is not from actual tropical cyclones or hurricanes, you can probably expect drier conditions this year, or at least more variable rainfall from less organized systems as more precipitation will be produced from local influences. El Niño does tend to delay the onset of the Southwest Monsoon, so that could be something to watch next year, although it may not have much impact this year. In Texas, the switch to neutral conditions means rain in April through June is more likely, which would be great for avoiding drought. If you live in an area that does not receive much moisture from the tropics, it will be hard to make a good forecast because the statistics just don’t give much guidance. We do know that globally, El Niño years tend to be very warm, so it is likely that 2023 may be one of the warmest, if not THE warmest, since global records began in 1880 due to the long-term rise in temperature from greenhouse warming. Warmer weather will mean a longer growing season, more hot days and nights, more humid conditions (unless a drought occurs), and more diseases and pests that thrive on the warmer conditions.

What do we expect next winter?

If you like to plan far ahead, you can see seasonal forecasts from NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center at Climate Prediction Center – Seasonal Outlook (noaa.gov). If you are not from the United States, your own country’s weather service may provide similar outlooks for your region. Here in the US, we are likely to see wetter and cooler conditions in the southern US as the jet stream steers storm systems over us (days will be cooler because of the clouds, but nights won’t necessarily be colder than usual since clouds trap nighttime heat). In northern states, warmer and drier conditions will be more likely, and that could mean an earlier start to the growing season next year. Now that something to look forward to if you are a gardener!

Tulipa “El Niño” 2015, Retired electrician, Commons Wikimedia.