Gardeners are assaulted with marketing campaigns nowhere better than in the fertilizer aisle of a garden center. There are so many choices and the labels suggest that fertilizing garden plants is a complicated process that requires specialized products.

Laws require that fertilizers list the proportion of the most important macronutrients on the front of the bag. Nitrogen, Phosphorus and Potassium abbreviated N, P, K, respectively, will always be shown with the ratio of their concentrations such as 5-10-15. This indicates the bag contains 5% nitrogen, 10% phosphorus and 15% potassium. The bag will also specify the weight of fertilizer contained in it, usually in pounds here in the United States. Of course, labeling requirements vary in other countries. Since fertilizers are not drugs or pesticides the labeling requirements are relatively lax and thus are open to extensive marketing. With fertilizers, as long as the contents are labeled and the proportion of N P and K are somewhere on the bag, any other claim can seemingly be made.

For years fertilizers have been designed specifically for certain plants. You can commonly purchase citrus food, camellia and azalea food, vegetable fertilizer, and of course turfgrass fertilizers which have been widely marketed for decades. Some fertilizer blends are based on research. Turfgrasses have a high requirement for both Nitrogen and Potassium and you often see elevated percentages of these in turfgrass fertilizers. Palms also require more potassium than Phosphorus and products have been developed that are “palm special” fertilizers. Despite all the research, manufacturers still throw in some phosphorus even though phosphorus is abundant in the United states in most soils. It is not clear to me what makes citrus food different from any other fertilizer, although claims that it is best for citrus can usually be found on the product. We grow more citrus in Ventura County, particularly lemons than anywhere in California, but none of the growers apply “citrus food”.

Some fertilizers are marketed for acid loving plants. Acid forming fertilizers have the ability to temporarily reduce pH in media or soil to which they are applied. This is because they have a high amount of ammonium or urea as the nitrogen source. Microbes in soil oxidize the nitrogen to nitrate and release hydrogen ions that make the soil more acid. Continual use of acid forming fertilizers can drop soil pH to dangerously low levels and make nutrients unavailable to many plants. This is especially the case in high rainfall climates where mineral nutrients are easily leached from soil. Another product often used to lower pH is aluminum sulfate. Often marketed as “hydrangea food” it helps to promote blue flowers in this plant. Special care should be given here as aluminum can easily be applied to toxic levels.

For as long as fertilizers have been sold they have been marketed as products that make plants grow better. When the importance of mycorrhizae were discovered, manufacturers found a new marketing angle that could be used to sell fertilizers. Now countless manufacturers include mycorrhizal inoculants as part of their fertilizer blend. Not only are we able to feed the plant but we can also feed the soil with beneficial micro-organisms. This all sounds great but often the inoculant, if present in the bag, is not viable. In many cases garden soils already have plenty of mycorrhizal fungi in them so they really are not needed in fertilizer products. Other fertilizers include growth stimulants such as humic acid, fulvic acid or humates. Research does not support their efficacy in horticulture.

Fertilizer manufacturers feel that it is important that we gardeners use things that are “all natural”. I don’t know what is natural to you but for me it is natural to challenge claims that have no scientific basis. The very practice of fertilizing plants is NOT NATURAL! But the products are often purported to be. Sometimes natural is synonymous with organic. There are an amazing number of organic fertilizers, so much so that it becomes bewildering as to which one to choose. Organic fertilizers may or may not be ‘certified’ by an agency such as OMRI as meeting some standard. Generally speaking organic fertilizers are made from some carbon based source. They can be sourced as manures or as plant or animal based meals or products. The N-P-K ratios vary widely.

I am always careful to avoid manure-based organic fertilizer products as they can be unnecessarily salty. While many organic fertilizers may be rather “slow release” as they need to mineralize from organic to soluble forms, this is often not the case with manure based products which can easily burn plants if over-applied. Some organic fertilizers are made from rock like substances such as leonardite which are very slow releasers of nitrogen. These products are mined and are similar to coal but have fertilizer value. In trials I have conducted on containerized plants some of these products were top performers.

Another common type of organic fertilizer are the biosolids products such as Milorganite. These are processed sewage sludge products that are de-watered and made into fertilizer. They are very effective nitrogen sources. Some biosolids fertilizers have also been sources of metals, such as zinc, lead and cadmium. Metal contents are closely monitored by manufacturers but since these products come through municipal systems, zinc, copper and other metals such as lead are often elevated. Slow release and organic fertilizers are useful if they are applied with understanding of the mineral needs of the plants they are applied to.

Most plants grow fine without fertilization and the main fertilizer element that plants respond to is nitrogen. So despite all the marketing claims seen on fertilizer bags, a fertilizer with an adequate source of nitrogen will likely benefit plants in need of that element. Specialized fertilizers that promote flowers or roots are not substantiated by research. Elements other than nitrogen are usually not required and ratios of N P and K are not tuned for more blooms or more roots. Adding phosphorus to your fertilizer does not promote flowering unless your soil is deficient in phosphorus (a rare condition). Gardens in high rainfall areas will likely need more potassium and nitrogen, but Phosphorus is hardly ever limiting to plant growth. Most plants do not need or require special fertilizers but will respond to fertilizers that contain an element they and soils they are growing in are lacking.

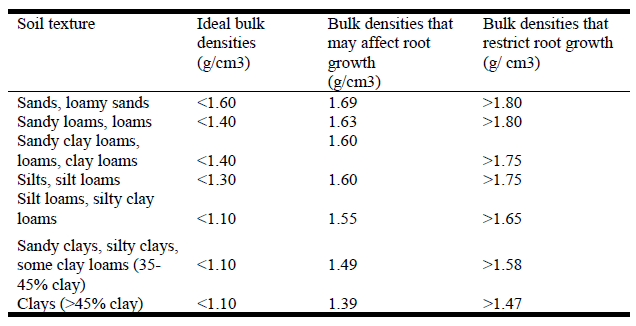

For gardens that have a loam soil texture, little fertilizer will be needed. Soil types often determine fertilizer needs for plants. Sandy soils likely need the most fertilizer because they do not hold nutrients well. They are also the most likely soils to lead to pollution because fertilizer elements will leach easily. Plants growing in sandy soils are also at greatest risk from injury of overfertilization. Plants growing in clay soils are least likely to require fertilization because clays hold and retain cations so well. An informed way to fertilize your garden is to obtain a soils test and base your fertilizer program on the results you obtain. For more on technical details of fertilizing see John Porter’s column in this blog archive.

When you think you need to fertilize garden plants follow these suggestions:

-Base your fertilizer program on a soils test

-Fertilize sandy soils more frequently than clay soils but with smaller amounts

-Most gardens require some nitrogen but not Phosphorus or Potassium so look for NPK ratios with X-0-0 as these products will only supply nitrogen.

-Some plants such as palms and turfgrass benefit from potassium so use a product with X-0-X

-Do not fertilize at planting time, wait until plants establish

-Always apply water after applying soluble fertilizers so they are dissolved

-If using Organic fertilizers chose one with a higher N content

-Never over-fertilize. Landscape fertilization can impair natural waterways resulting in algal blooms that kill fish and other aquatic life.