After getting off to a cool and soggy start, summer has come with a vengeance to Michigan, with heat indices expected to push 100 degrees by Wednesday. Along with warmer temperatures, summer also means our research season is getting into full swing as well. One of our biggest efforts these days involves our project to look at pre-plant storage and handling on shade tree liners.

As many GP blog readers are aware, emerald ash borer (EAB) has dominated the conversation regarding shade trees in the Midwest for the past 6-8 years. Ashes made up 20 to 30% of the shade tree cover in many urban and community forests, so their loss has been devastating. A major thrust of our extension programming during this time is to promote a wide range of ash alternative to increase species diversity. One of the challenges we find in making this pitch is that many of the species we recommend (oaks, hackberry, baldcypress) are trees that nurseries often find difficult to grow from standard bare-root liners.

My graduate student, Dana Ellison, is in the second year of a project to look at some of the practices that growers use on the difficult to transplant species and some of the underlying causes of poor transplanting. Dana is looking at a variety of attributes including plant water relations and carbohydrate status, but the order of business these days is roots. Specifically we’re evaluating root growth potential of oak, baldcypress, and hackberry. We’ve also included white ash, which transplant easily, as a positive control.

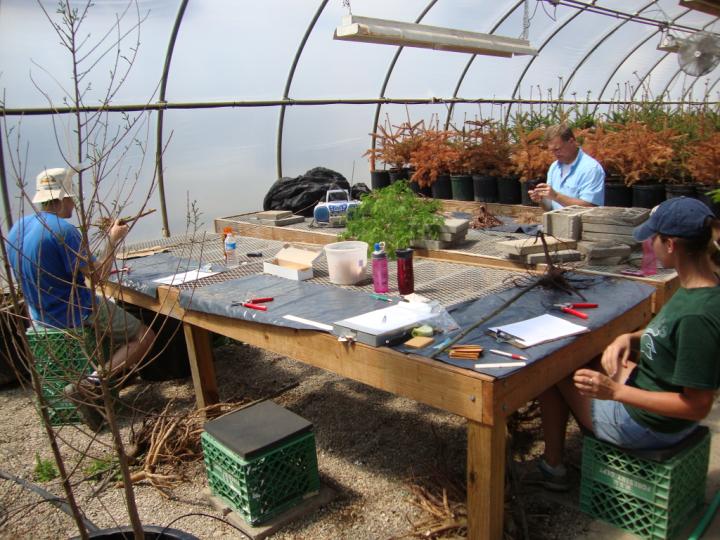

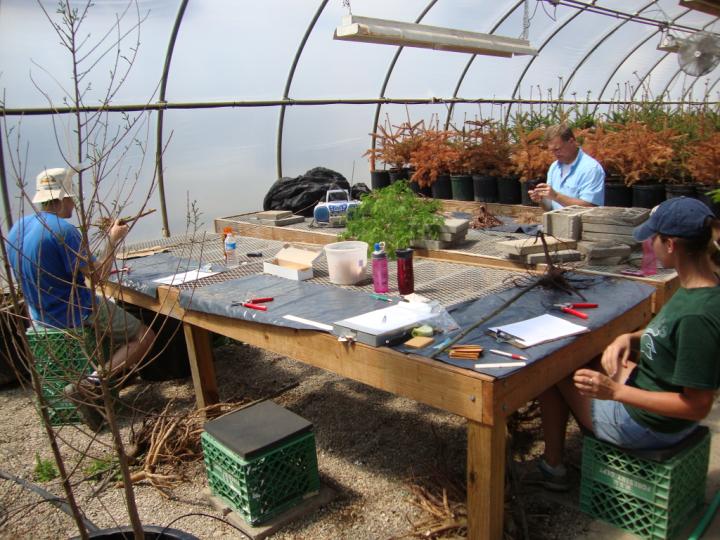

Graduate research assistants Dana Ellison (right) and Brent Crain (left) and undergraduate assistant Arriana Wilcox (center) pot up shade trees for root growth potential testing.

Root growth potential (RGP) is a common parameter in evaluating quality of reforestation seedlings but is measured less often on larger liner material. The logic is pretty straightforward; a plant’s ability to initiate root growth after plating and re-establish root-soil contact is one of the biggest determinants of its ability to survive and grow. A variety of systems have been used to evaluate RGP for seedlings – most involve growing seedlings for a set time (3 weeks is standard) in an aeroponic system and then counting or measuring new root growth.

Growing the trees in pea gravel makes it easy to get a look at new roots.

For Dana’s shade tree liners (5’-6’ whips) we’ve adapted a system based on the Missouri gravel bed system (which I first got to see in person at Jeff’s research nursery in Minnesota – thanks Jeff!). Dana and her helpers pot the trees up in pea gravel in 25-gallon containers. The trees are grown on for three weeks in a greenhouse while the roots are kept moist with spray stakes operated by a mist system timer. After three weeks, we dump out the gravel, wash the root systems, and carefully count the number of new, white root tips.

Dana washing roots.

So what have we learned? Well, the work is still on-going but some trends have emerged. Baldcypress may experience some transplant issues but they don’t appear to be related to producing roots. We had several baldcypress trees that produced 400 or more new roots during the RGP test – and, yes, we counted them all! Red oak and northern pin oak, on the other hand, are very slow to put out new roots. For hackberry trees, our other measurements suggest their transplanting issues may be related to their inability to re-hydrate after lifting, storage and transport. These insights should help us provide some guidelines to growers to help them produce a wide pallet of trees for the landscape market and increase species diversity in the wake of EAB.

Counting roots. Almost as much fun as it sounds…

The defending champion baldcypress: 614 new roots.