“Why don’t you just plant it up against the house,” piped my mother-in-law. She was talking about a run-of-the-mill “old fashioned lilac” that we had received in the mail for our donation to Arbor Day. While I don’t necessarily think of the organized tn as a source of high-quality or novel plants, I felt beholden to make a donation since it was founded and is still located in Nebraska (and we have visited the Arbor Lodge, home to founder J. Sterling Morton and his brood of tycoons (one of salt fame – that Morton, one of cornstarch fame – ergo we have Argo, and one of the railroad). I had pawned the 10 blue spruce off to the freebie table at the office, but she wanted a lilac…and what momma-in-law wants, momma-in-law gets.

I explained to her that the labeled final size of the cultivar was 12 feet in diameter, so it needed to be at least 6 feet from the house (preferably more) and from other plants. “Nonsense!” she decried, “I planted mine close to the house. You just have to keep it pruned back. Mine did just fine….. until it rotted.” Since the right spacing would put the shrub in the middle of a narrow passage between the house and the fence, I opted to throw it into a pot since I was heading out of the country the next day for two weeks. It was, after all, a little more than a spindly twig (with roots wrapped together in a ball) sheathed in plastic.

What’s the issue?

Most gardener’s desire for instant gratification often means that correct spacing for the finished size of the plant gets thrown out the window so that the garden looks good to go from the beginning. Or even worse, plants get shoved against houses, under power lines, or in other areas where they’ll either be cramped and crowded or incessantly pruned to the point of oblivion throughout their probably shorter-than-expected lifespan. Think of it like your bubble of personal space. Just like you don’t want to be crowded, neither do plants.

In addition to the pruning and space issues, crowding can increase the likelihood of disease or other plant issues. Crowded plants reduce air flow, which aids the development of diseases by increasing (ever so slightly) the humidity in the plant’s microclimate, increasing drying times after rain or irrigation, and even allowing for disease spores to more easily settle on the plants. For perennials, and especially trees and shrubs, overcrowding can be a chronic issue since the problem can last for many, many years.

That’s not to say that spacing it isn’t a problem with annuals, either, especially in the vegetable garden. In addition to the increased possibility of disease, competition for space and for nutrients can reduce yields. Crowded root crops like carrots, beets, and radishes don’t have enough space to fill out, resulting in stunted and irregular produce. The same goes for leafy crops like lettuce or kale. Fruiting crops like tomatoes and peppers can also suffer from reduced production when plants can’t fully grow to their potential.

Getting Spacing Right: The Simple Art of Not Planting Too Damn Close

Perhaps the secret is complicated formula for figuring out the proper plant spacing? Or perhaps it is some specific planetary alignment you need to wait for? Since it seems to mystify may gardeners, spacing must be difficult, right? Au contrare!

Most plants come with the proper space printed right on the label! Think of such a novelty! That lilac my MIL wanted to plant against the house said right on the packaging that it generally grew to 12’ wide. If I were planting a bunch of them in a row (and not as a hedge), I could plant them 12’ apart. If I wanted to grow them as a hedge, I’d reduce that spacing to make them grow into each other (but it will take time for them to grow into a hedge…so they won’t be touching right away). Keep in mind that this is the genetic potential of the plant and isn’t a guarantee. Many factors, including microclimate, soil conditions, precipitation, nutrient availability, disease, etc. etc. etc. could limit the plant’s growth to that potential (or even more rarely increase it). What if I’m not planting a bunch in a row? Here’s were a teensy bit of math comes into play.

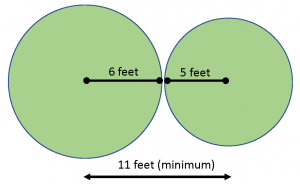

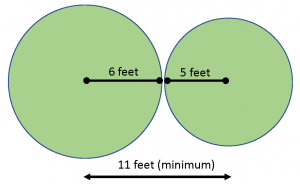

Think of plants in general terms as circles. Just look at a basic landscape architect’s plans and you’ll sometimes see plants represented generally as circles. If you think all the way back to that geometry class in high school, you’ll remember that there are several measures of a circle, including the diameter and the radius. The diameter is the width of the circle from one side to the other. The radius is the distance from the center point of the circle to the edge. So if our plant is a circle, then the listed width of the plant is the diameter and the distance from the trunk, stem, or center is the radius.  So I can expect my lilac (if it reaches full potential) to grow out 6 feet from the trunk. That means I need to plant it at least 6 feet away from the wall. If I wanted to plant it in the landscape with other plants around it, I would need to figure out the radius of the plants I wanted to plant close to it and add their radius to the lilac radius to figure the minimum distance I should plant them apart. Let’s say I wanted to plant a small shrub beside the lilac with listed width of 10 feet. That means the radius of that shrub is 5 feet. Adding them together, I get a distance of 11 feet. On the other side of the lilac I want to plant a large perennial with a diameter of 4 feet. The radius would be 2 feet, so my minimum planting distance would be 8 feet. You also have to keep in mind any variation due to microclimate and environmental factors.

So I can expect my lilac (if it reaches full potential) to grow out 6 feet from the trunk. That means I need to plant it at least 6 feet away from the wall. If I wanted to plant it in the landscape with other plants around it, I would need to figure out the radius of the plants I wanted to plant close to it and add their radius to the lilac radius to figure the minimum distance I should plant them apart. Let’s say I wanted to plant a small shrub beside the lilac with listed width of 10 feet. That means the radius of that shrub is 5 feet. Adding them together, I get a distance of 11 feet. On the other side of the lilac I want to plant a large perennial with a diameter of 4 feet. The radius would be 2 feet, so my minimum planting distance would be 8 feet. You also have to keep in mind any variation due to microclimate and environmental factors.

What about the vegetable garden?

The same concept holds true for the vegetable garden as well – think of each of the plants as a circle. Where planning the spacing is different is usually interpreting what the seed packet says in terms of in-row versus between-row spacing. The in-row spacing is based on the size of the plant, a general idea of the size of the circle the plant makes or how much space it needs between plants (some plants, like beans, are OK when they overlap a bit and share space). The between-row spacing is for human use in creating typical in-ground, large garden areas. I’ve had the discussion before of large garden area vs. in-ground beds, vs. raised beds so we don’t need to go into that detail, but the general movement is toward some sort of bed system to reduce walkways (reducing bare soil that can lead to erosion or compaction when walked on) and intensify plant spacing/output per a given area.

Taking that into consideration, use the in-row spacing as the between plant spacing in all directions. This is what the popular Square Foot Gardening method does – the spacings and number of plants per square are based on the between plant spacing and eliminates row spacing. For example, radishes and carrots typically have an in-row or between plant spacing of 3 inches. If you fit that spacing evenly within a foot row segment, you get four plants. When you make that two dimensional you get 16 plants per square foot. For four inch spacing you get 3 per foot and 9 per square foot, six inch spacing you get two and four, etc. You can fill an entire bed with plants like this without spacing between rows of plants.

Of course, the tricky thing is that, just like our trees and shrubs that are planted too closely reduced airflow and increased microclimate humidity can increase the risk of diseases in the plants. The Square Foot Gardening method by the book states that you shouldn’t plant any adjacent square with the same crop to decrease likelihood of disease sharing, but that seems sounder in theory than in practicality. I use some of the spacing (and you don’t need the book, just look at the between plant spacing and calculate. You just have to monitor, use good IPM, and treat or remove issues promptly to reduce disease issues. Using interplanting to intensively plant by mixing various space usages (tall plants with short plants, root crops with fruit crops) can also help make use of the space while mixing plants to reduce disease spread.