Since my last post, the news has been full of one weather disaster after another. Wildfires in Maui. The remains of Hurricane Hilary moving north into California and other parts of the western USA with moisture even streaming as far east as Wisconsin. Record-breaking heat and humidity across most of the continental USA and severe weather outbreaks in the Midwest and Northeast. This does not even include the typhoons, floods, droughts, and heat waves occurring in other parts of the world at the same time. And today I am watching the development of a tropical system in the northwestern Caribbean that is likely to become Tropical Storm or Hurricane Idalia (pronounced ee-DAL-ya) by early next week, bringing rain and strong winds to parts of Florida and southeastern Georgia.

Each of these weather events can impact our gardens and properties. Not all the impacts are bad since tropical rainfall is an important source of summer moisture in many areas. In the Southeast as much as 40% of our summer precipitation comes from tropical systems and if we don’t get that rain, we can go into a drought quickly in our hot summertime temperatures. The rain from the remains of Hurricane Hilary helped provide some needed rain to help increase reservoir levels in the desert Southwest USA, which desperately needs the water. But if we get too much very strong rain or winds the damage to our homes and yards can be severe. This week I want to discuss some ways you can prepare your gardens and landscaping for the severe weather that will inevitably occur in your area at some point in the future (and that future may be nearer than you think).

Awareness is key to proper preparation

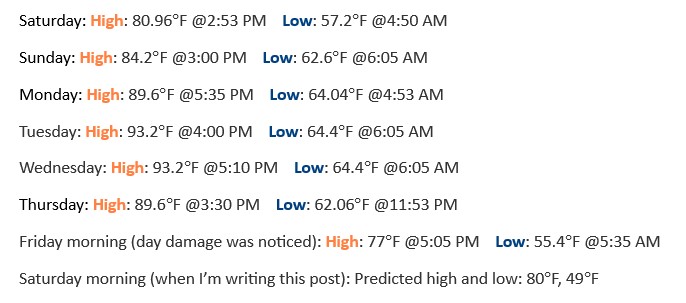

To properly prepare your gardens and homes for severe weather, you need to know what kinds of weather to expect and how it will impact your plants and buildings. The types of weather you are likely to experience will drive how you prepare. If you live in the Pacific Northwest, you are not too likely to experience hurricanes, but you certainly can experience extreme rain storms in winter and wildfires in summer especially if you have a heat wave like you did last year. If you live in the Southeast then hurricanes and tropical storms are much more likely but damage from straight-line winds can be just as important, as I found out in late July when strong thunderstorms knocked down so many trees in my neighborhood that we lost power for 44 hours. A friend of mine lost the roof of her house to two pine trees that toppled over in the strong winds. We can even experience ice and snow storms here in the South from time to time; this means you should not just prepare for the most common disasters but for any extreme event that could occur there. Of course, getting ready for the most common natural hazards is the best way to save your homes and gardens because those are the most likely to occur where you live. But you should also think about rare events like floods even if you are not in a flood plain because the consequences of an event are so severe.

Once you have identified the natural hazards that affect your area, then you need to think about what kinds of weather conditions are likely to occur in each of those events. In a hurricane or a strong winter storm on the West Coast, heavy rain and high winds are both likely weather conditions your garden will experience. In a heat wave, high evaporation rates and dangerous outdoor working conditions are likely to be the major dangers. Those are the impacts you will need to consider when protecting gardens and gardeners.

Look at your landscape and home to identify potential problems

Once you have determined what hazards are likely to affect your property, you need to do an assessment of where your risks are. Take a walk around your garden and look at the trees and plants you have. Are there dead trees that could fall over or broken limbs that could snap off in high winds from hurricanes or thunderstorms and become wind-borne missiles? Do you have garden decorations like garden gnomes or mirror balls that could also blow into the sides of cars or buildings? Do you live in an area that is prone to frequent flooding? How will you keep that water away from your house and out of your garden plots? Are there a lot of plants close to your home where they could spread wildfire in a drought under gusty winds?

After you have determined the risks take steps to minimize or remove those risks where you can. There are a number of ways that you can storm-proof your house and garden, many of which should be done anyway to maintain your garden’s health.

I was interested to read the story of the lone house in Lahaina, Hawaii, that survived the recent fires that destroyed much of the town because they had a large area around the foundation covered by river rock, which did not burn and helped keep fire from igniting the house (although I am sure there was some luck involved there too). One of my favorite books, The Control of Nature by John McPhee, also describes the increase in debris flows in western landscapes that occur due to fires that burn waxy plants. This creates perfect conditions for rapid land movement downhill after rain events following the fires, often right through people’s yards and houses.

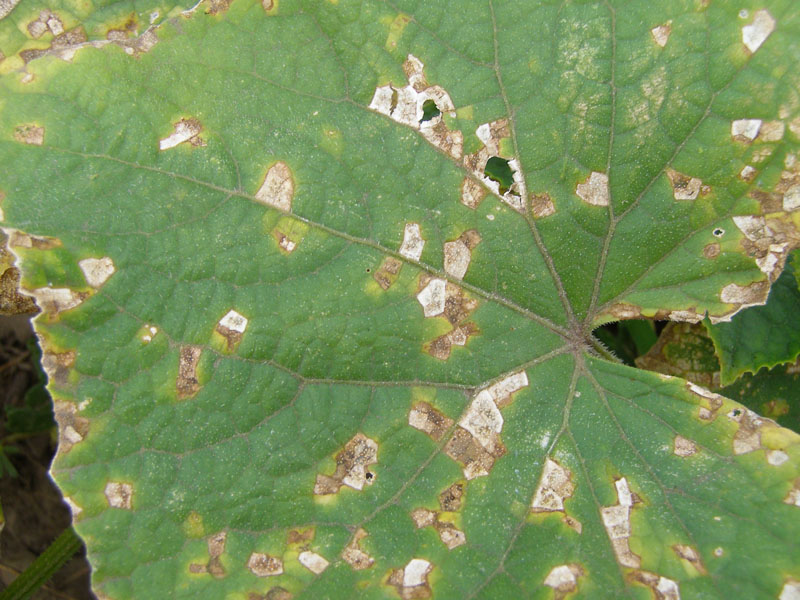

After the storm is over and you are safe, then it is time to assess your garden and house for damage and take care of your plants, lawns, and buildings. Be careful since there may be downed power lines and dangling tree limbs that could be hazardous. You may need professional help to prune or remove trees or clean out contaminated soil after flooding. Once the immediate hazards are taken care of, then the longer-term work of repairing drainage, eliminating the effects of erosion, rebuilding beds, and other work can begin.

Take care of your family and pets too

Of course, all this planning for your garden and property should not take the place of emergency planning for your own family. If extreme weather does occur, you need to have a plan already in place to determine where to shelter in your home if you can and how to evacuate safely if you can’t stay. Every minute saved makes a difference although in the worst cases even that may not be enough time. FEMA has a good website that provides a lot of information on how to plan for both natural hazards and other emergencies like chemical spills. Many states also have excellent resources for dealing with emergencies, such as the Resident’s Handbook To Prepare for Natural Hazards in Georgia, which covers all kinds of severe weather and how to prepare for it in Georgia and beyond.