Regular blog readers will remember that we moved to my childhood home a few years ago. With an acre or so of landscape I finally have enough room to put in a vegetable garden. My husband built a wonderful raised bed system, complete with critter fencing, and we’ve been enjoying the fresh greens and the first few tomatoes of the season.

We filled these raised beds with native soil. During a porch addition I asked the contractor to stockpile the topsoil near the raised beds. The house was built almost 100 years ago and at that time there were no “designed topsoils” (thank goodness) – soil was simply moved around during construction. Some of this soil had been covered by pavers and the rest had been covered with turf. [You can read more about designed topsoils in this publication under “choosing soil for raised beds.”] There had been no addition of nutrients for at least 7 years so I was confident that this was about as natural a soil as I could expect.

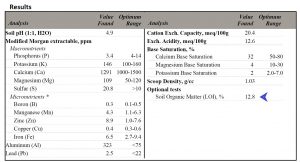

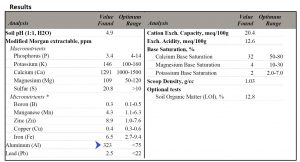

I’ve always advised gardeners to have a soil test done whenever they embark on a new garden or landscape project, so before I added anything to my raised beds I took samples and sent them to the soil testing lab at University of Massachusetts at Amherst (my go-to lab as there are no longer any university labs in Washington State for the public to use).

What I already knew about our soil was that it’s a glacial till (in other words it’s full of rocks left behind by a receding glacier). The area is full of native Garry oak (Quercus garryana), some of which are centuries old. The soil is excessively drained, meaning it’s probably a sandy loam. And that’s about all I knew until my results came back.

Because nothing has been added to this soil for several years, and because I had removed all of the turf grass before filling the beds, I assumed that the organic matter (OM) would be quite low. Most soils that support tree growth have around 3-7% OM. Hah! Ours was over 12%! All I can figure is that centuries of leaf litter has created a rich organic soil.

So here’s lesson number one: Don’t add OM just because you think you need it. Too much OM creates overly rich conditions that can reduce the natural protective chemicals in vegetation. This means pests and diseases are more likely to be problems.

I was pleased to see our P level was low. First soil test I’ve ever seen in my area where P was below the desirable range! Does that mean I’m adding P? No – because there is no evidence of a P deficiency anywhere in the landscape. And my garden plants are growing just fine without it.

Lesson number two: Just because a nutrient is reportedly deficient, look for evidence of that deficiency before you add it. It’s a lot easier to add something than it is to remove it.

Likewise, our other nutrient values are just fine, and I was pleased to see that lead levels were low. Given that this is an older house that had lead paint at one time, and given the fact that the soil being tested was adjacent to the house, I was prepared for lead problems.

Likewise, our other nutrient values are just fine, and I was pleased to see that lead levels were low. Given that this is an older house that had lead paint at one time, and given the fact that the soil being tested was adjacent to the house, I was prepared for lead problems.

However – we do have high aluminum in the soil. Exactly why…I don’t know. Perhaps the soil is naturally high in aluminum? There’s no evidence that aluminum sulfate or another amendment was ever used. In any case, that was an unexpected result that does give us some concern for root crops. I’ll be doing some research to see what vegetables accumulate aluminum.

Finally, note our pH – 4.9! This is completely normal for our area, which is naturally acidic. In addition, the tannic acid accumulation from centuries of oak leaves has undoubtedly pushed the pH even lower. Are we going to adjust it? Again, no. There is no evidence of any plant problems, and even our lawn is green. Why would we adjust the pH if there is no visual evidence to support that?

Which leads to lesson number three: Don’t adjust your soil pH just because you think you should. If your plants are growing well, the pH is fine. Plants and their associated root microbes are pretty well adapted to obtaining the necessary nutrients. If you have problems, don’t assume it’s a pH issue. Correlation does not equal causation! You’ll need to eliminate all other possibilities before attempting to change your soil chemistry. And remember it is impossible to permanently change soil pH over the short term. Permanent pH changes require decades, if not centuries of annual inputs (like our oak leaves).

Will I test my soil again? Probably not. I have the baseline report and since I don’t plan to add anything I don’t expect it to change much. If I had a nutrient toxicity I would retest until the level of that nutrient had decreased to normal levels. But with everything growing well, from lawn to vegetables to shrubs and trees, there really is nothing to be concerned about.

Lesson number four: Unless you have something in your soil to worry about, don’t.