I was pleased to see that at least two of you dug into the literature over the weekend to read these papers! (I can still remember the first time as a Master’s student when I was assigned a journal paper to review. I had NO idea what, exactly, I was supposed to be doing. It took a long time to figure it out.)

In any case, kudos to Jimbo and Diana for their thoughtful comments – and for zooming in on the problems. Indeed, Jeff and I conclude there is likely a fertilizer effect on the plants – and a healthy plant is better able to resist insects. Secondly, the speculation at the end of the paper regarding root uptake of phenolics from the vermicompost – compounds that weren’t even measured, much less monitored for uptake – is totally unsubstantiated and in fact is not feasible, given root physiology. I’ve pasted my draft to the journal editors below, which explains this a bit more. (Jeff also has some choice things to say, and I’ve added his comments as well.)

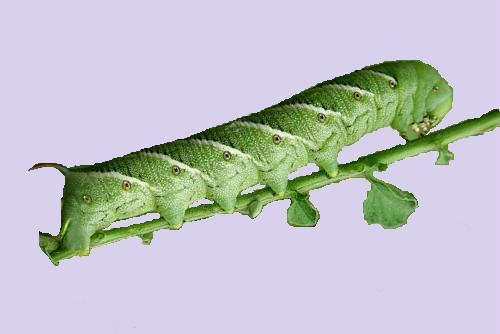

From LCS: “I recently read the article by Edwards et al. entitled “Suppression of green peach aphid (Myzus persicae) (Sulz.), citrus mealybug (Planococcus citri) (Risso), and two spotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) (Koch.) attacks on tomatoes and cucumbers by aqueous extracts from vermicomposts” (29(1): 80-93).

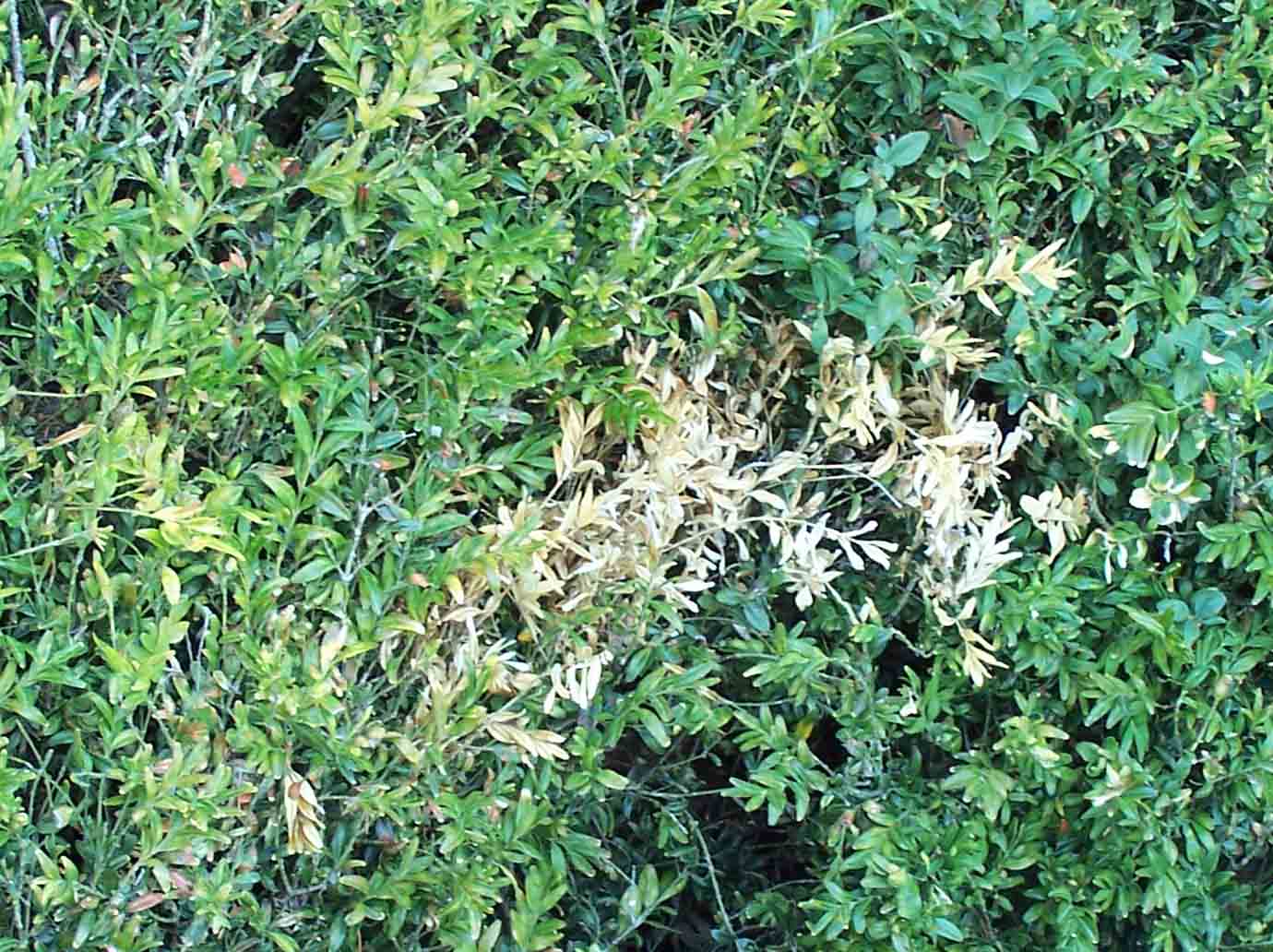

“The article presents evidence that the use of vermicompost teas increased the resistance to damage from these pests. As the authors state “there are many reports in the literature of organic nutrient sources decreasing numbers of pest arthropods.” This seems a logical conclusion given that the authors have provided an additional nutrient source to their treated plants (vermicompost extract) that was not available to the control plants (which were drenched with water). The treated plants were better able to manufacture anti-herbivore compounds as a result.

“Yet the authors then venture into unsupported speculation that this resistance was due to the uptake and transport of water-soluble phenols by the roots and into the leaves of these plants. In the authors’ words: “these diverse results all point to the probability that water-soluble phenols, extracted from the vermicompost during aquatic extraction, taken up into plants from soil receiving drenches of vermicompost aqueous extracts, could be the most likely mechanisms by which vermicompost aqueous extracts can suppress pest attacks.”

“Not only are there no data or other direct evidence to support this speculation, but the likelihood of such uptake is highly unlikely if not impossible. The water/nutrient uptake mechanism in plant roots is cellularly regulated, particularly at the endodermis, where all solutes must pass through cell membranes prior to entering the vascular tissue. No such transport has ever been documented in the literature, though the authors report “There have also been suggestions of these effects being due to the uptake into plants of phenols from organic manures (Ravi et al., 2006).” This latter paper, however, measures the presence of phenols and their associated enzymes in the plant tissues, not the uptake of soluble phenolics. Plant physiologists and biochemists have long known that plants are capable of synthesizing a wide variety of phenolic compounds used to ameliorate abiotic and biotic environmental stresses. I am surprised that the authors did not discuss their theory with plant scientists at their institutions.

“It is disappointing that the authors were not discouraged during the peer-review process from making unsubstantiated, fantastic claims about the mechanisms underlying their research results. ”

From Jeff: “Though we do not discount the possibility that compounds may have been present in the vermicompost that could have been taken up by the plant’s roots, we think it much more likely that there was a fertilization effect which caused the plants to grow more rapidly and/or which allowed the plant to defend itself more effectively using its own defensive mechanisms. The authors of this paper discount this effect by stating that “It could not be caused by uptake of soluble nutrients since all of the experimental treatments were supplied regularly with all the nutrients that they needed from Peter’s Nutrient Solution, which was applied to the experimental plants three times a week.” but do not include any evidence to back this statement up. This is a fatal flaw. In fact, the authors don’t even provide any data regarding the concentration of nutrients that were added. Simply stating the analysis of the Peter’s fertilizer which was used provides us little data as they could have mixed this up at any concentration before applying. Was nitrogen applied at 10ppm? 600ppm? Likewise, though the authors tell us the concentration of nutrients in the vermicompost used, no indication of the amount of nutrition in the compost extracts is given. If these analyses of nutrient content turned out to be too expensive the authors could simply have grown additional plants without exposing them to the insect pests. By then comparing plants which had been grown with extracts to those grown without the effects of the extracts on growth would have been made obvious. Another significant problem with this paper was the lack of information regarding the variety of tomato which was grown. Tomatoes have various resistance mechanisms to defend themselves from insect pests including, but not limited to, both glandular and non-glandular trichomes. Many papers over the years have shown that the density and chemical composition of these trichomes is affected by both the plants parentage and by nutrient concentration.

“In short, it is difficult to believe that even a novice researcher would provide the paucity of information and experimental data that these researchers did which might elucidate the presence or absence of a fertilization effect. The fact that the first author of this study is a seasoned researcher gives the impression that the objectivity of this research has been compromised. This impression is only strengthened when we discover, at the end of the paper, that this research was funded as a subcontract to a grant for small businesses, in this case the Oregon Soil Corporation. It seems logical to assume that this paper was published as a gimmick to promote the business interests of a producer of vermicompost rather than for any furthering of science. You have done your journal a great disservice by publishing it.”