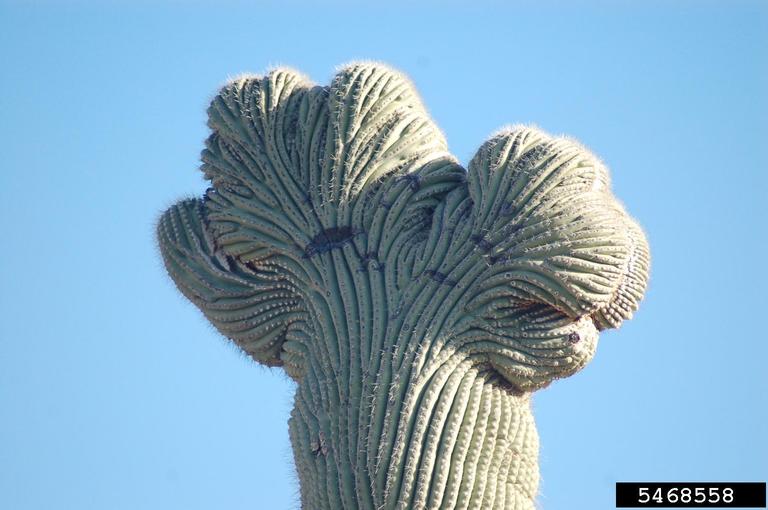

You may have seen it on the odd flower or plant here and there or you may be intentionally growing plants that show this unique and uncommon phenomenon. Fasciation (not fascination- though it certainly is pretty fascinating) is a malformation or abnormal pattern of growth in the apical meristem (growing tip) of plants. The apical meristem is undifferentiated tissue that triggers the growth of new cells (which extends roots and shoots, and gives rise to stems, leaves, and reproductive structures). In the case of fasciation (which originates from the Latin ‘fascia’ which means ‘band’ or ‘bundle’), this new growth is abnormal and often appears as flattening, ribboning, swelling, fusion, or elongation of plant parts. Sometimes referred to as ‘cresting’, this can occur anywhere on the plant but is more likely to be seen in stems, flowers, and fruit. You might encounter this as several stems growing together, a multi-headed or misshapen flower, perpendicular or irregular growth, dense tuft-like growth, or coiled, contorted, and twisted stems which can sometimes have an unusually high concentration of leaves and flower buds.

There are multiple patterns of fasciation that can be observed, including: linear fasciation (which results in the more common flattened and ribbon-shaped stems), bifurcated fasciation (when a linear fasciation splits in two to form a “Y” shape), multiradiate fasciation (where the stems split into three or more short branches, referred to as a ‘witches’ broom’), or the rare ring fasciation (where the growing point folds over to form a hollow shoot) (Geneve, 1990).

Fasciation is a symptom that can be caused by a variety of different factors including genetics, hormones, pathogens (including bacteria, viruses, and phytoplasmas), injury (including chemical, mechanical, and feeding damage), nutrient deficiency, or environmental causes (such as temperature extremes) though in many cases it is still not completely understood and the exact cause may not be apparent in a specific fasciated plant. The stability of this phenomenon is also pretty variable. Some plants can pass on this trait through their seeds (resulting in a genetic likelihood of expressing this symptom), while other plants can develop fasciation (through a variety of causes) and then resume normal growth from a fasciated point, or perennial plants that appear fasciated one year may be completely normal the next year. Scientists have even identified some of the specific genes in which mutation can cause fasciation and have experimentally reproduced this result in seedlings that were exposed to radiation, chemical mutagens, and high temperatures.

Most often fasciation is just an aesthetic anomaly, is fairly uncommon, and rarely impacts the survival of affected plants (especially if they are established woody plants). In cases of fasciation due to infection by certain pathogens (such as the bacterium Rhodococcus fascians), it is possible for affected plant parts to die prematurely. Although infectious fasciation can spread to other susceptible plants, in the majority of cases fasciation is not infectious and will not spread.

Although fasciation can occur on any plant (and has been documented in hundreds of plant species) it is more frequently seen in certain groups such as cacti, daisies, asters, legumes, willows, and plants in the rose family (Rosaceae). It is also more common in plants with indeterminate growth.

In some cases, distinct examples of fasciated plants are intentionally selected for their visual appeal and interest. Many times, plants that have a greater propensity for fasciation, or those that can be vegetatively propagated are developed into cultivars that can be sold (and are often a striking addition in any garden). Many of our dwarf conifers, for example, are propagated from witches’ broom cuttings. In addition, some of our large and uniquely shaped tomato varieties, such as beefsteaks, are selected for their fasciated fruit, and many strawberries that have a wider shape or appear to be ‘fused together’ are also fasciated and considered desirable.

Examples of plants that frequently exhibit fasciation, including those with cultivars that you can purchase for your gardens, are ‘cockscomb’ celosia (Celosia argentea var. cristata), ‘fascination’ culver’s root (Veronicastrum virginicum or sibiricum ‘Fascination’), ‘crested’ hens and chicks (Sempervivum spp. var. cristata), and Japanese fantail willow (Salix sachalinensis ‘Sekka’), among others.

If this strange growth is something you don’t enjoy, you can prune out the distorted tissue. Or if you’re like me – you can just marvel at the weird and the wonderful!

Resources

Fascinating

Fasciation (Wisconsin Master Gardeners):

https://mastergardener.extension.wisc.edu/files/2015/12/fasciation.pdf

Plant of the

Week: Fasciated Plants (University of Arkansas):

https://www.uaex.uada.edu/yard-garden/resource-library/plant-week/fasciated-2-22-08.aspx

The Genetics

of Fasciation:

https://trinityssr.files.wordpress.com/2016/06/4th-ape.pdf

Fasciation (University of California IPM)

https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/GARDEN/FLOWERS/DISEASE/fasciation.html

Fascinated with Fasciation (Dr. R. Geneve, 1990, American Horticulturist)

https://ahsgardening.org/wp-content/pdfs/1990-08r.pdf

This is a fascinating article; thanks for putting it in here. Did you notice that the plant identified by North Carolina State as “tickseed” (Coreopsis) is actually a Gaillardia?

Great catch! You are right!