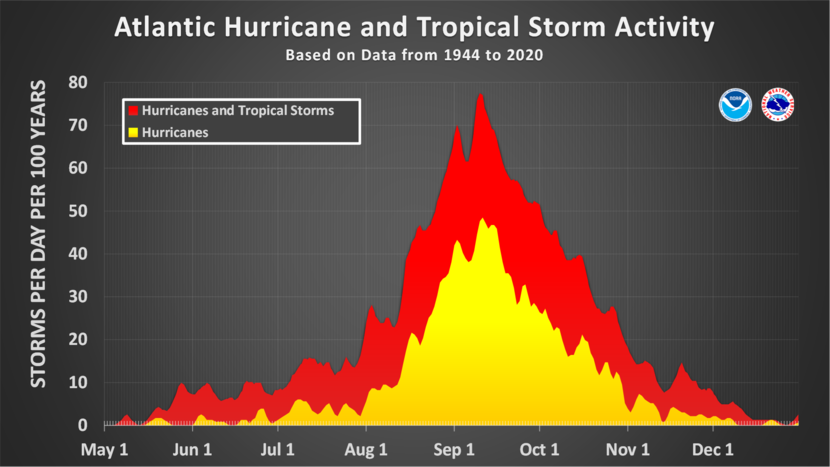

In the Southeast, almost nothing gets more press than the Atlantic Tropical Season, including the outlooks, real-time events, and post-storm analyses. If you live in another part of the United States or the world, you may not be as directly affected as the Southeast is, but you might be surprised at how far and wide tropical moisture is spread, either directly by tropical storms and hurricanes or by the remnant moisture which can be carried with the winds for long distances away from their original sources. This week I will describe what tropical systems are and what they mean for gardeners. In my next post, I will review the current season, including any impacts that have occurred. Don’t let the early quiet conditions fool you—about 90% of Atlantic tropical activity occurs from mid-August through mid-October.

What is a tropical system?

I am using “tropical system” as a term that encompasses the life cycle of a tropical disturbance from birth to death. That may include formation by a tropical wave coming off Africa, developing in the Gulf of Mexico, or growing in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, then a tropical storm, a hurricane (maybe even a major one), and eventually a slow death as a tropical depression or extra-tropical low that has lost its tropical characteristics.

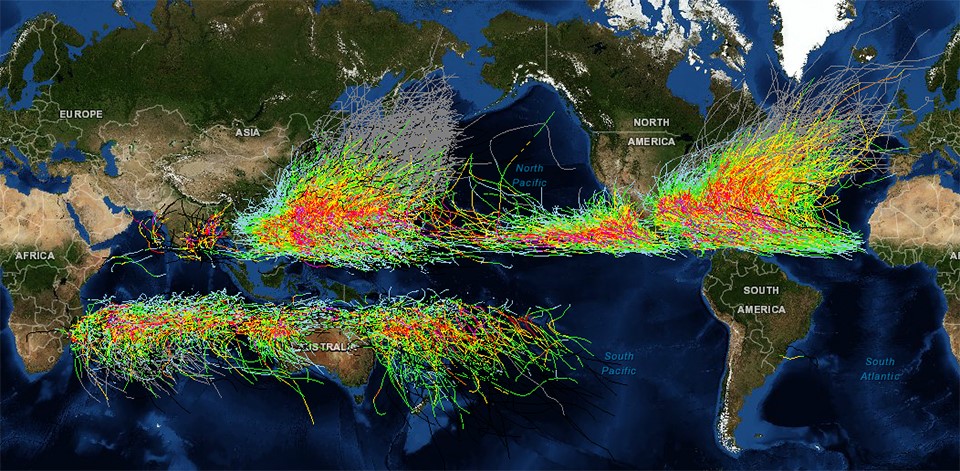

The map below shows historical tracks for all known storms across the globe. Note that in some regions they are called hurricanes and others, typhoons, but both are tropical cyclones, the generic name for rotating, organized systems of thunderstorms that originate over tropical waters and have closed, low-level circulations. The pattern of tracks shows some interesting information about tropical systems. For example, why are there almost no tracks in the eastern part of the South Pacific Ocean or in the southern Atlantic? Why do many of the tracks show a curve as the storm moves from east to west? Why are there more storms in the Northern Hemisphere (NH) than in the Southern (SH)? Why are there almost no tracks along the equator?

What ingredients are needed for tropical systems to develop?

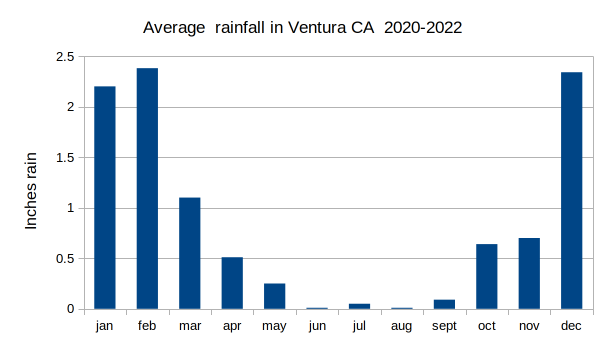

Tropical systems form from areas of low pressure that develop rotation (counterclockwise in the NH and clockwise in the SH) as the storms’ pressure decreases. For the storm to strengthen, it needs favorable conditions to cause rising air in the center, which drops the pressure at the surface. One ingredient is ocean surface temperature of 80 F or higher (27 C)—that explains why almost no storms develop in the southeastern Pacific or southern Atlantic, since both are far too cold. Tropical storms and hurricanes are considered to be “warm core” systems with the air in the center of the storm staying warm all the way to the top of the circulation. The peak season of storms in the Atlantic is related to the cycle of ocean temperatures, with the highest likelihood of storms in the period from mid-August to mid-October. As ocean temperatures warm, this could mean a shift in hurricane season in the future.

For spin to develop, you need a force called the Coriolis force that affects the atmosphere due to the earth’s rotation around its axis. The Coriolis force is zero at the equator so any areas of low pressure that form in that area can’t develop the necessary spin to form storms. Another ingredient is light winds higher up in the atmosphere. This allows the vertical structure of the storm to develop a strong circulation that ultimately becomes a hurricane. This becomes important when we talk about the impacts of El Nino and La Nina on predictions of tropical seasons, since El Nino years have much stronger jet streams in tropical regions than La Nina or neutral conditions do.

The curvature of the tracks is due to the mid-level winds in the atmosphere that steer the storms as they go through their life cycles. The counterclockwise flow of air around ridges of high pressure systems push the storms along their edges. This often results in a C-shaped pattern as the storm travels around the western edge of the oceanic high pressure, although the position and strength of the high pressure will help determine the path each storm takes and when or if it recurves to the northeast.

Impacts of tropical systems

Some impacts of tropical systems are only found near the center of the circulation, but others can be found hundreds of miles away, so even if you are not in the main area that tropical storms affect, you are not without risk. These storms are not small whirls like tornadoes, but are much bigger and can take hours to cross a location near the center. If you are close to the storm’s center, especially if you are on the right side of the storm’s path, you are likely to experience strong winds, heavy rain, and, if you are near the coast, the chance of a storm surge coming inland from the ocean. Farther away, you can experience strong squalls that include small tornadoes, heavy rains, and gusty winds. These effects are made worse if you live in mountainous areas where lifted air can cause rapid flooding conditions. Some of the worst floods in U. S. history are from former hurricanes that traveled over mountains and dropped incredible amounts of rain, such as Agnes, which caused the death of 122 people mostly in Pennsylvania, almost exactly 50 years ago.

Even after a storm weakens to a depression or transforms into an extra-tropical storm, the blob of moisture within the remains of the storm can be transported by the atmospheric circulation a long ways. There have been records of typhoons in the Western Pacific Ocean whose watery remains crossed the ocean and brought heavy rain to the West Coast. Occasionally some will enter the central United States and drop flooding rain there, too, such as the remains of Tropical Storm Erin in 2007.

What gardeners (and everyone else) should know

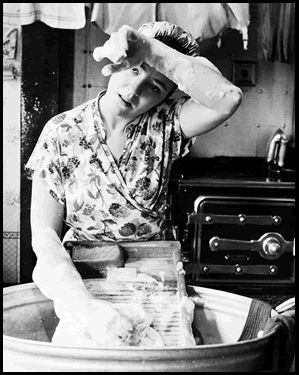

Preparing a garden for a hurricane is no different than preparing for other types of extreme weather. Survey your property before the season to make sure that no objects that could blow around in high winds damaged are present. If a storm is coming, make sure that your yard is free of garden gnomes, rakes, damaged tree limbs, or other loose objects that could become airborne. Make sure your roofs and gutters can shed heavy rain and have a place on your property to contain rainwater safely. Have supplies of batteries, non-perishable food, and water for people and pets. Put together a plan to recover later by making inventories of your property, including outdoor equipment that you store online. And make a family plan for how to evacuate if you live in an area of flooding and how to contact each other later if you get separated. Cell phones often do not work after strong wind events, so you can’t count on them to bring your family back together quickly after a storm.

What’s next?

I expect to see the Atlantic tropical season start to pick up by mid-August, when the African dust that is currently inhibiting storm formation clears and the ocean temperatures get even warmer. In fact, today’s 5-day outlook map shows an area of possible development in the eastern Atlantic (as of 8-6-2022). This is expected to be another active season, and even though we’ve only had three named storms so far, we will likely see many more storms before the end of November, when the official season ends. In my next blog, we will look at the season so far in more detail.