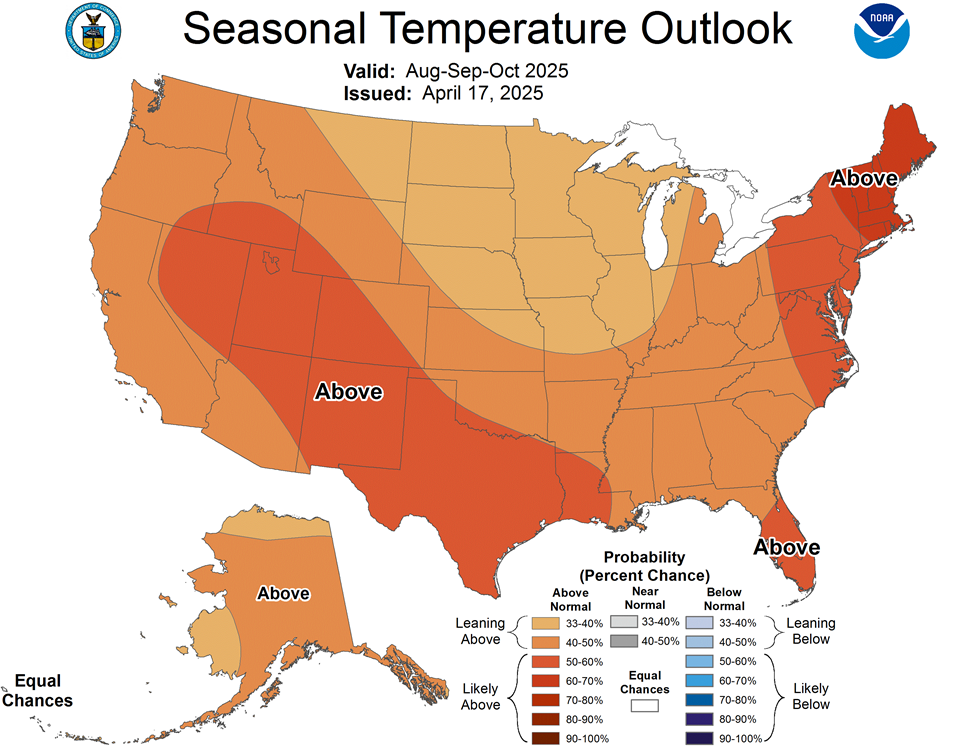

If you’ve been paying attention to the weather across the United States this past week, you may have noticed that most of the eastern U. S. is experiencing extremely hot temperatures, especially when you factor in the effects of humidity. At the same time, in the western U. S., it has been snowing in the mountains, even though it is almost July! In this week’s blog post we will look at why this pattern of hot and cold conditions occurs so often and what is causing it.

Heat in the East

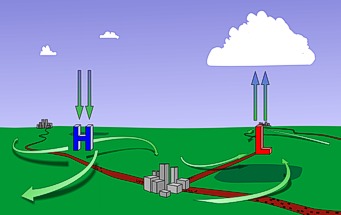

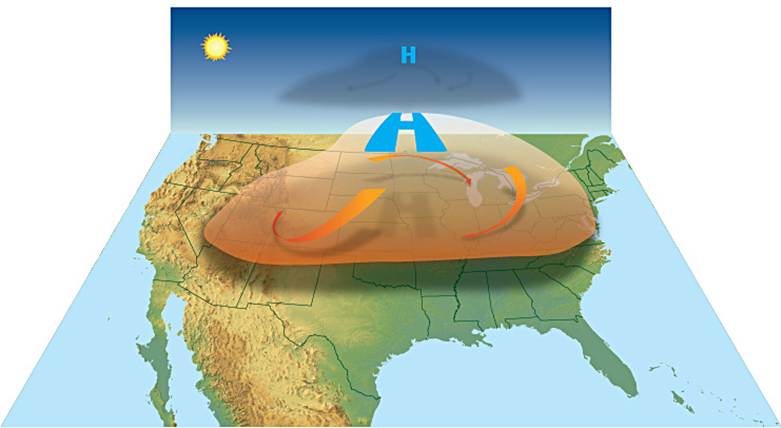

We have talked about persistent areas of very high temperatures several times in past blog posts (for example, here and here). Those areas most commonly form in summer under stagnant areas of high pressure that have sinking motion in the middle of the high. The sinking motion of the air keeps clouds and rain from developing, leading to very hot and dry air being trapped near the earth’s surface, raising temperatures and reducing wind speeds. Often those areas also include a lot of humidity, which makes the temperatures more oppressive because sweating does not cool you off efficiently if the humidity is high, especially if winds are also light.

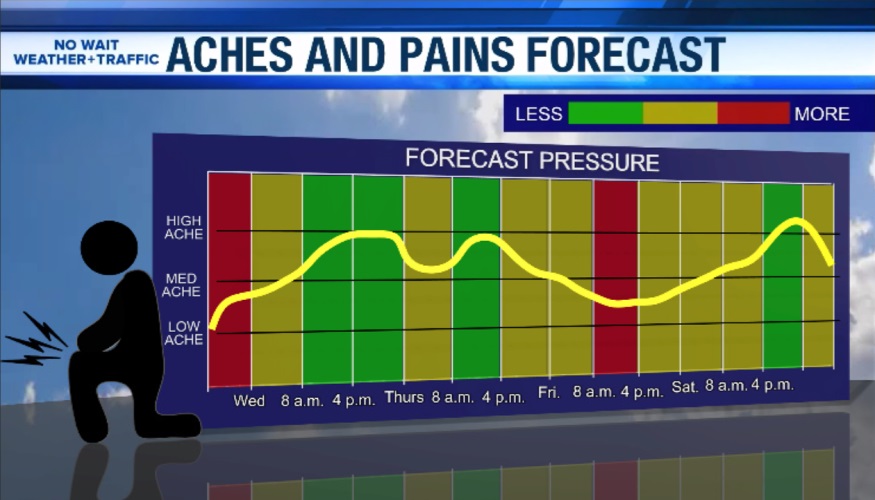

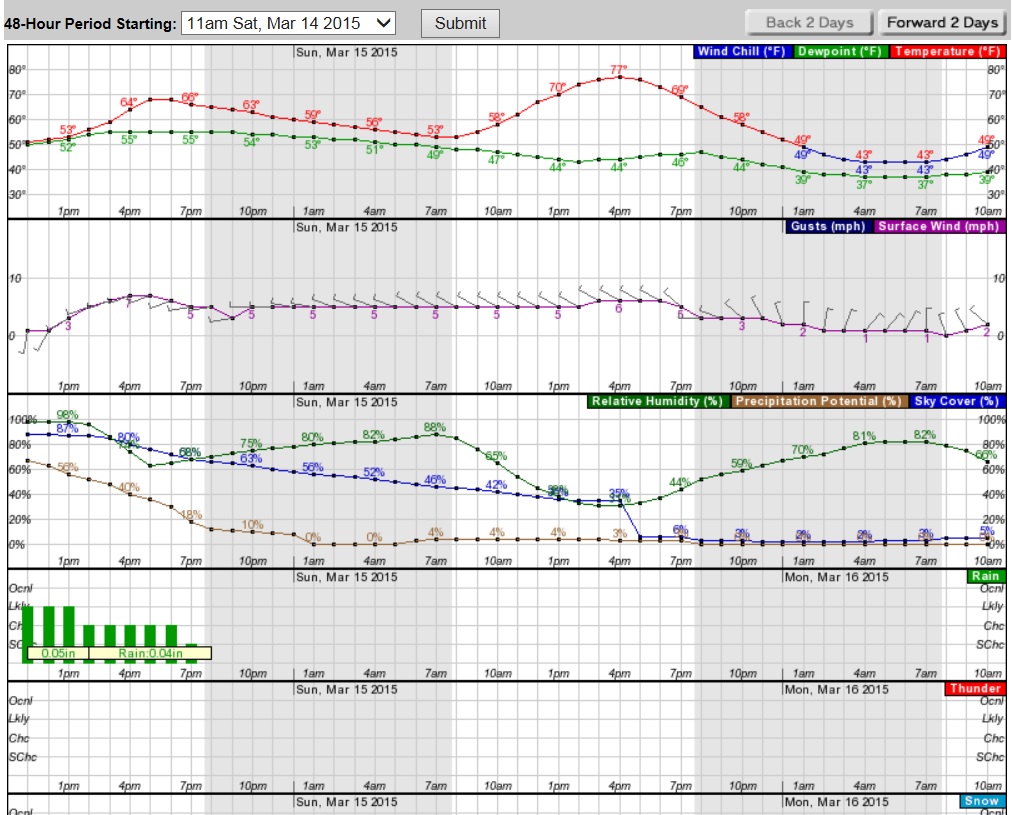

When this happens, the National Weather Service will put out heat advisories or other statements reminding people to be careful to keep cool and stay out of the hot sun as a way to prevent heat-related illnesses like heat stroke. This is also important for gardeners, who like to spend time outside tending their plants and gardens. You can monitor the atmospheric conditions associated with heat to identify times when it would be better to stay inside where it is cool by using the National Weather Service’s HeatRisk map or the Southeast Regional Climate Center’s Wet Bulb Globe Temperature forecast tool (which is for the entire country, not just the Southeast).

Note that heat domes don’t always occur in eastern parts of the country. A deadly heat dome occurred in the Pacific Northwest (PNW) in late June 2021, breaking numerous high temperature records and killing 136 people in Washington alone in the period from June 26 through July 6, 2021. In that case it was the West that was under unusually high temperatures while the Eastern U. S. was cooler than usual. They also occur in other parts of the world, and in fact this week Europe is also experiencing very high temperatures due to another region of high pressure parked over them.

It is also interesting to note that in winter, areas of high pressure are often the coldest areas of the country due to the lack of cloud cover, which allows heat from the earth to escape to space, leaving colder conditions at the surface at night when no sun is there to heat the ground.

Cold and snow in the West

On the other end of the country, cold air was trapped on the other side of the frontal boundary between the eastern high-pressure center and the low-pressure trough that was present in the western U. S. The cold air was so intense, especially at higher elevations, that snow fell in some mountainous areas of western Montana and surrounding states. The Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier National Park had to be closed from June 20 to June 23 due to the heavy snow.

What connects these two extremes together?

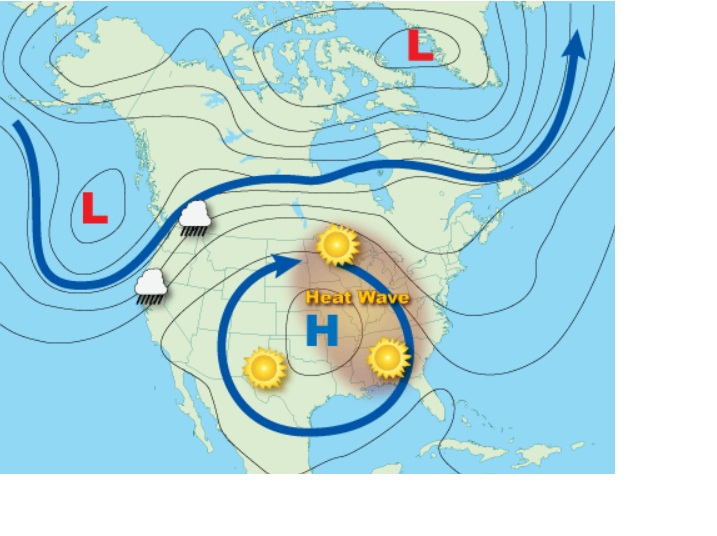

The common connection between the heat in the East and the snow in the West is the large-scale atmospheric wave that is linked to both the low pressure in the west and the high pressure in the East. The atmosphere is a fluid and is constantly adjusting its pressure fields by forming waves with ridges of high pressure as well as troughs of low pressure. Sometimes these patterns get locked in place for a few days (or even longer in rare cases), which leads to more extreme effects, but they usually move on in a few days, causing the weather to go back to normal conditions or even flip-flopping to the opposite pattern. In fact, we discussed atmospheric waves back in July 2021 following the PNW extreme heat event in this blog.

The surface weather associated with these areas of high and low pressure are what cause the big changes in observed conditions that gardeners and farmers have to deal with since they can have big impacts on flowers and crops. The atmospheric wave pattern can lock in place for a number of reasons including conditions in other parts of the earth such as unusually cold or warm water in the ocean or droughts or floods in other areas. Fortunately, these stationary patterns usually shift or break down after a few days, leading to big changes in local weather conditions that might be more welcome.

How do cold and hot outbreaks affect gardens?

Most garden plants are fairly resilient to the changes in temperature, humidity, winds, and cloudiness that come with the shifts in the atmospheric waves and their associated surface weather. Plants respond differently to heat than humans and other animals do because they don’t sweat. High heat can cause the plants to close the stoma in their leaves to retain moisture, but a long enough period of high temperatures and dry conditions with little soil moisture leads to wilting and eventually, death of the plants. Of course, most gardeners are watering their gardens to avoid this worst case!

Cold spells in summer do not cause as much damage as frost and snow in spring and fall because they just don’t get cold enough to damage the plants (unless you are in the mountains and the temperatures drop below freezing), but they can slow the plants’ growth and reduce their flower or fruit production. Food crops that depend on a significant number of growing degree days (a measure of the accumulation of heat over time based on daily temperatures) will grow more slowly, resulting in late harvest of whatever crop is being grown. In the worst cases, it could delay harvest so late in fall that fall frosts become a consideration, but most home gardeners do not need to worry about this as much as commercial farmers because they are not farming hundreds of acres of crops, just their own patch of land.

I encourage you to visit some of the links in the article above to learn more about heat domes and atmospheric waves as well as their impact on your garden plants. You can also use the search field to find additional sources of information about any topic of gardening that you might want to learn more about, especially one that relates to the science of gardening. It’s a great resource!