Once again we wander down the path of botanical history.

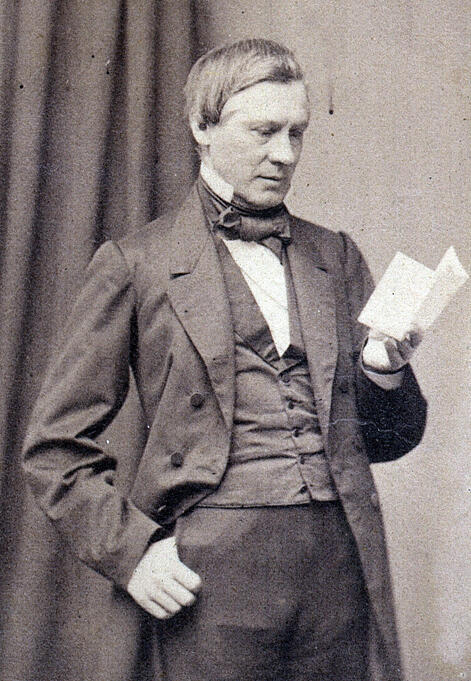

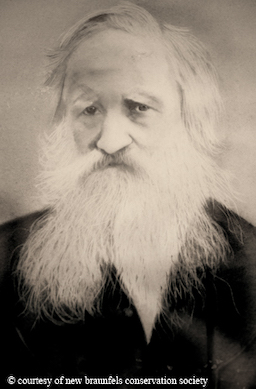

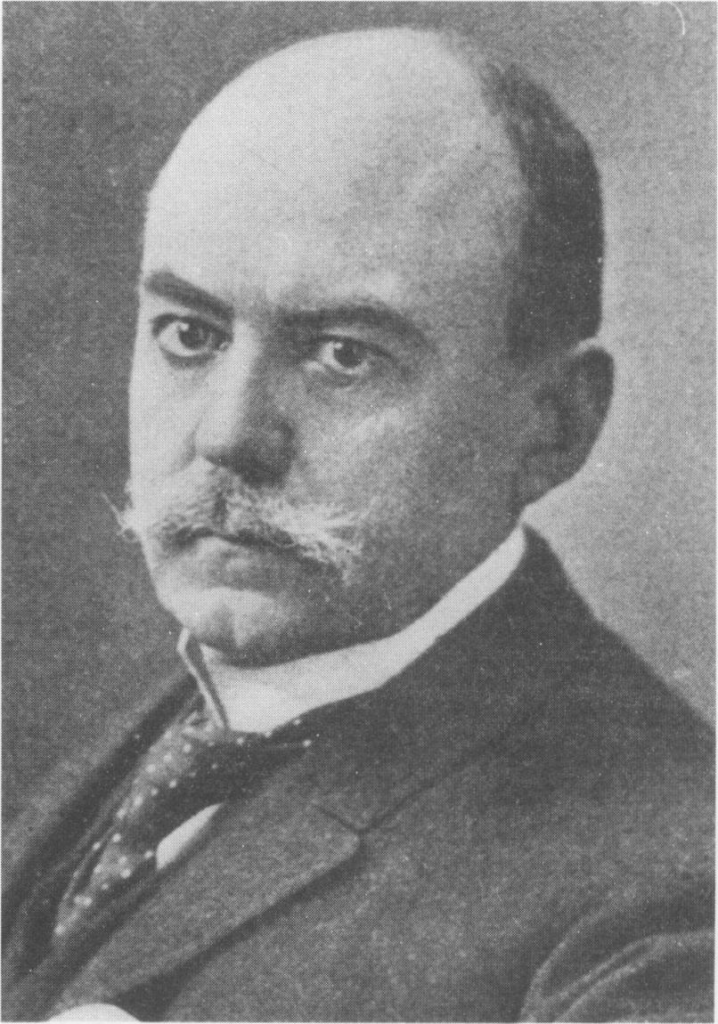

George Julius Engelmann was a botanist, physician, and meteorologist, but is remembered primarily for his botanical monographs. George, also known as Georg, was born Feb. 2, 1809 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, the oldest of thirteen children, nine of whom reached maturity. Unusual for the time, his parents established and ran a successful school for young women there in Frankfurt.

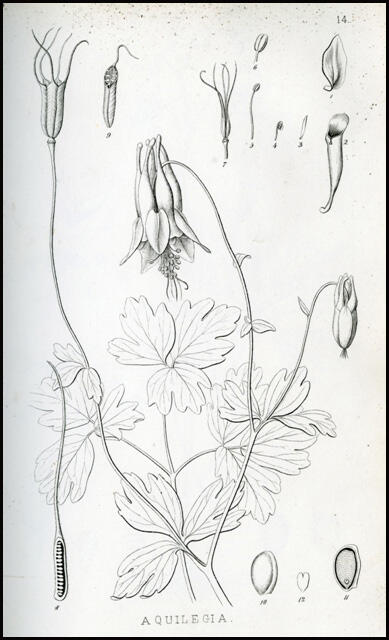

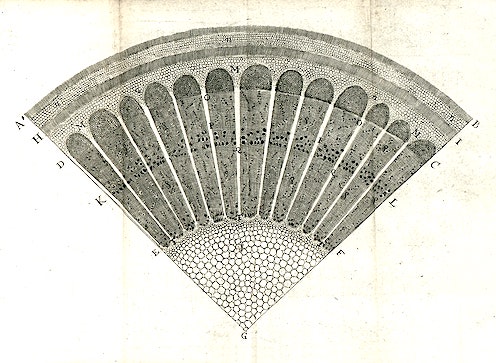

Like most privileged young men of the time, George attended gymnasium. He started to take an interest in plants when he was 15 but was also keen on history, languages, and drawing. With the help of a scholarship, 1827 found him studying sciences at the University of Heidelberg. In 1828 young Engelmann, being embarrassed by his participation in a recent student political demonstration, decided to transfer to the University of Berlin for a couple of years. He then moved on to the University of Würzburg where he graduated in 1831 as a Doctor of Medicine. With shades of things to come, his dissertation for the medical degree was more related to botany than to medicine. It was devoted to morphology, the structure and forms of plants, and was illustrated with five plates of figures drawn and transferred to the lithographic stone by Engelmann himself. It was published in Frankfurt in 1832 under the title of De Antholysi Prodromus.

Spring and summer of 1832 found him in Paris where he was leading, ” a glorious life…in spite of the cholera,” but changes were on the horizon. His uncles wanted to make land investments along the Mississippi River and enlisted him to be their agent. In September of that year George sailed from Bremen to Baltimore and made his way to family already living in Illinois near St. Louis. For the next three years, to get a better lay of the land which he’d been hired to sell, he made many long horseback journeys alone through southern Illinois, Missouri, and Arkansas. While he did use his recently acquired regional knowledge in his new job, his botanical notes waited to be used in the future.

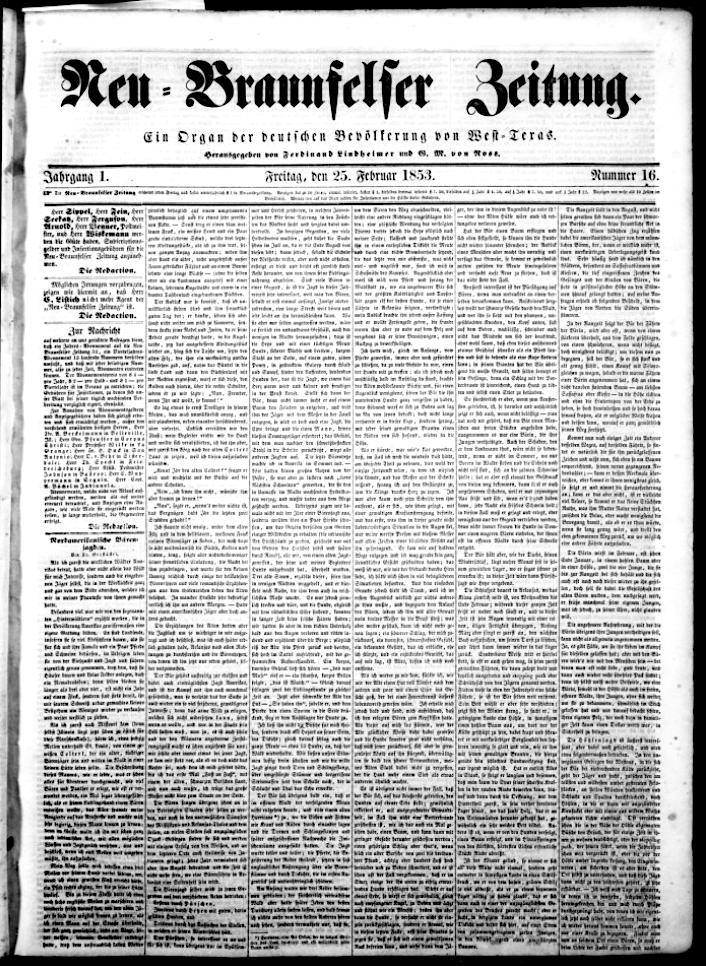

Tiring of the land agent role by late 1835, he moved to St. Louis to start a medical practise. Apparently needing more to do, in 1836 he founded a German newspaper called Das Westland. It contained articles on life and manners in the United States and was widely read and appreciated in the United States and Europe. Four years later his medical practise was well established and he’d earned enough money to make a trip back to his hometown. There he fell in love, got married, and the newlyweds then returned to America. When they landed in New York City Engelmann met Asa Gray, already a well known American botanist. A close friendship developed between the two which was ended only by death.

Eventually Engelmann’s medical practise in St. Louis became so successful he no longer needed to keep office hours: he simply saw patients in his study. This allowed him to take long vacations and devote more time to his preferred botany and biology studies. An 1842 monograph on dodders, A Monograph of North American Cuscutinae, had established his reputation as a botanist. He was one of the earliest to study Vitis (the grape species) of North America; nearly all that is known scientifically of these plants is due to his investigations. One of his most economically important discoveries was of the immunity of the North American grape to the plant pest Phylloxera, which became very significant later in the century during The Great French Wine Blight.

In the 1870s French vineyards came under attack by Phylloxera vastatrix which feeds on grape vines roots. Growers observed that certain imported American vines were resistant to the insect’s feeding habits. The French government dispatched a scientist to St. Louis to consult with the Missouri state entomologist and Engelmann, who had studied American grapes since the 1850s. Engelmann verified that certain living American species had resisted Phylloxera for nearly 40 years. Additionally it was found that Vitis riparia, a wild grape of the Mississippi Valley, did not cross pollinate with less resistant species which was the cause of previous growing failures. Engelmann arranged to have millions of shoots and seeds of V. riparia sent to France which eventually provided Phylloxera resistant rootstock and saved the French wine industry.

Photo by Joachim Schmid

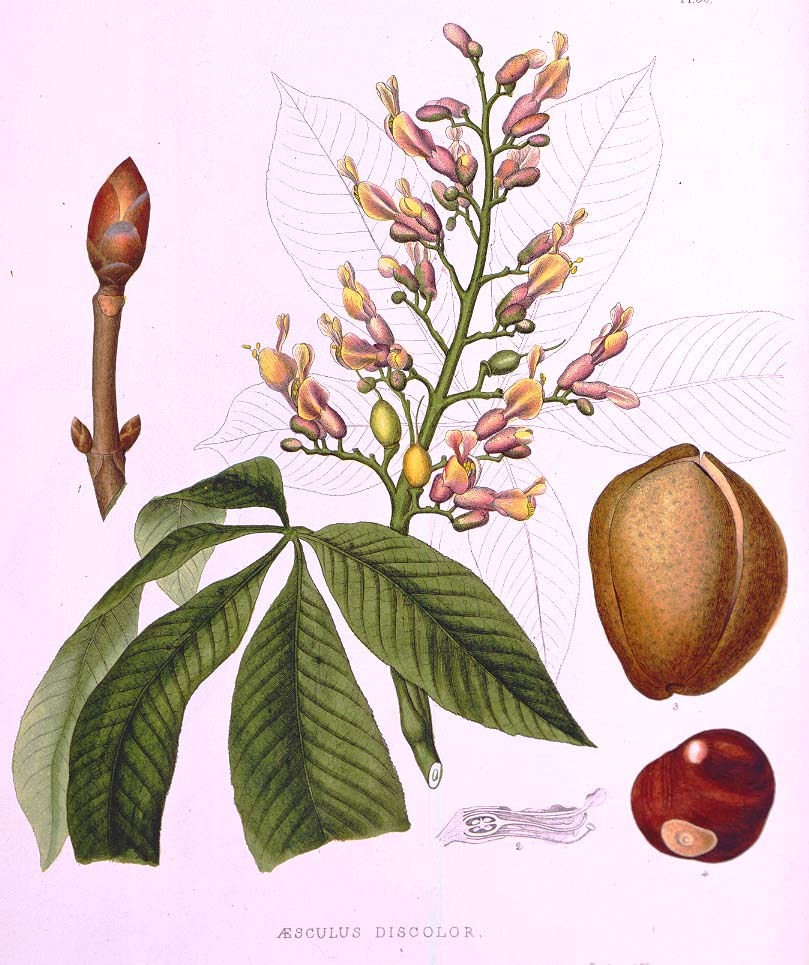

Other difficult plant groups Engelmann studied include cacti, conifers, mistletoes, rushes, and yuccas. In 1859, he published Cactaceae of the Boundary which studied cacti on the United States/Mexico border. A unique aspect of Engelmann’s cacti studies is he established, for the first time, the classification of these plants based on floral, fruit, and seed characteristics. The source he referenced for this was Dr. Wislizenus’ Expedition from Missouri to North Mexico. Engelmann eventually published two books on cacti, both of which are still valued references. Other monographs he published are Notes on the Genus Yucca (1873) and Notes on Agaves (1875). The latter was illustrated with photographs, which is something we tend to expect now but was quite forward thinking at the time.

In addition to his writing, both alone and in collaboration with others, Dr. Engelmann was also a founding member of the St. Louis Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Sciences. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Missouri Botanical Garden by encouraging Henry Shaw, a wealthy St. Louis businessman, to develop his already extensive gardens to be of scientific as well as public use. What was then called “Shaw’s Gardens” eventually became the Missouri Botanical Garden. Engelmann’s botanical collection, which contains the original specimens from which many western plants have been named and described, was given to the Missouri Botanical Garden. This gift of almost 100,000 specimens led to the founding of the Henry Shaw School of Botany at Washington University in St. Louis, where an Engelmann Professorship of Botany was established by Shaw in his honor. His legacy also lives through the many plant species named in his honor, including Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii), Engelmann spruce (Picea engelmannii), Apache pine (Pinus engelmannii), and Engelmann’s quillwort (Isoetes engelmannii).

Engelmann died in 1884. He was interred next to his wife, who passed away in 1879, in the Bellefontiane Cemetery in St. Louis.

The botanical works of the late George Engelmann, collected for Henry Shaw, esq. /Ed. by William Trelease and Asa Gray.

https://archive.org/details/mobot31753000060878

PPT on digitizing Engelmann’s collection

https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/digitizing-engelmanns-legacy-4745573/4745573