Pollinators, especially bees, are an important part of our agriculture, economy, and ecosystems. Gardeners are often well-versed in the importance of bees since we get the opportunity to see these incredible animals in action. We enjoy the results of their labor in the form of fruits, “vegetables”, and seeds which feed wildlife and create beauty and interest in our gardens. In North America alone, there is an estimated 4000 species of native bees, and an estimate of over 20,000 species around the world.

Many factors have played a role in bee declines, e.g., habitat loss, pesticide exposure, pest and disease pressures. Yet there are things home gardeners can do to help mitigate some of these effect and maximize the use of their yards and gardens as a ‘bee-friendly’ landscape. Habitat loss/fragmentation is considered to be amongst the most important factors influencing the decline of wild bee. Urbanization, development, agricultural intensification, etc. have also resulted in a reduction of high-quality habitat for these mostly native bee species.

Many gardeners even make room in their landscapes for pollinators by planting a variety of flowers that attract and help sustain their regional bee species. Although we are often well-versed in offering food for bees (in the form of these floral resources), something that can be overlooked in our endeavors of creating ‘bee habitat’ is the fact that we do not always offer them a place to live, or a ‘home’. Accessible nesting habitat for bees is just as important as floral resources and can make these pollinators’ jobs much easier as they make trips from flowers to their nests in order to provision them for their offspring.

Approximately 30% of bee species are above-ground cavity nesting bees most of which are solitary, meaning that a single female bee will do all the work to find a nesting location and provision the nest with nectar and pollen for her offspring to eat after she is gone. This can be quite a cumbersome task and offering suitable nesting habitat in close proximity to flowering plants we curate in our gardens can be a great way to simplify this undertaking for these momma bees.

Although mimicking the conditions of wild bee habitat as it’s found in nature is one of the best ways to offer a more natural nesting experience, urbanized areas with smaller spaces can often make this a difficult endeavor. In these areas where space is limited, artificial nesting structures for cavity nesting wild solitary bees, sometimes referred to as bee hotels and bee boxes, can be a useful tool for some bee species (which include mason bees, leafcutter bees, carder bees, and more). These bee hotels have been gaining popularity over the years and many people have started to jump on trend placing them around their yards and gardens. In the past 10 years, I have seen a huge variety of these nesting structures ranging from simple to very elaborate!

Even though there is widespread availability of bee hotels for sale, not all of them are equally as effective in being ‘bee friendly’, and some of these can actually be counter-productive to the health and well-being of these pollinators.

Here are some recommended specifications for artificial nesting structures for wild solitary bees:

Materials

Common materials used in effective bee hotels include drilled wooden blocks and trays and cardboard/bamboo tubes in addition to a box to place them all in. You want these boxes to be closed in the back and open in the front with some sort of a sloped roof so water will drip off and not collect around the nesting tubes.

Avoid using plastic materials/containers (and other things that will limit the ventilation of these structures as this can result in greater pest and disease issues). Very dark colored bee hotels, especially in locations with high sun intensity, can get really hot which can kill the bee larvae inside. It is best to use untreated and unpainted wood, cardboard and bamboo.

Depth/width and measurement specifications

One of the most common issues I see with some of these homemade and commercially available bee hotels are the depth and width measurements. Bees have control over the sex of the eggs that they lay and these cavity nesting bee species will organize their nests so that male eggs are laid near the entrance. These males will emerge first. In mason bees, for example, eggs laid further than 3 inches from the entrance are usually female bees. If the nesting structures are too shallow it can affect these sex ratios, resulting in a lower number of female bees. This can affect the local population.

Although there isn’t a perfect formula for all cavity nesting bee species and the size preferences of their nesting tubes, we know that some sizes work better than others. You should experiment with variations of size to cater to the bee species that can potentially utilize these nests.

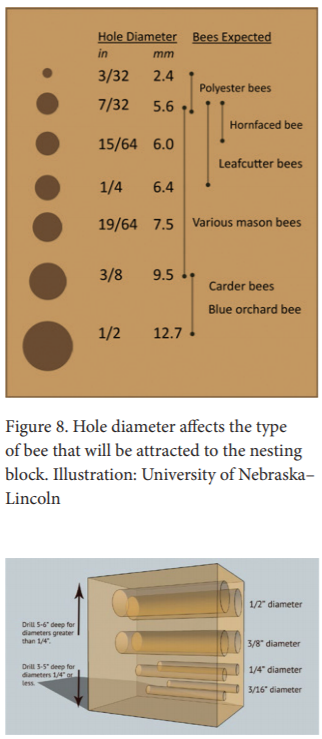

When drilling your own wooden blocks, drill holes of varying entrance sizes (between 3/32 and 3/8 inches in diameter) and depths (minimum 5-6 inches) into untreated wood blocks or old tree stumps/logs laying around your garden or wood pile. Don’t drill all the way through the wood, leaving one end closed. If you are buying a drilled wooden block-style bee box, make sure that it falls within the range of these depth and width recommendations.

You can also create bundles of cardboard tubes, bamboo reeds, and bundles of woody and pithy plants that can serve as a nice nesting substrate that bees will nest within and in-between. These bundles should also be placed in a container with a closed end.

Location

Bee hotels should be placed at about 3-5 feet off the ground. The entrance should have direct sunlight for the most of the day, especially early morning sun. This will help these cold-blooded animals heat up and get started on their foraging and nest building activities faster. Placing the entrance facing South or Southeast is a good location for many North American bee hotels. Make sure these are mounted on a sturdy location not be easily swayed or toppled over by the wind. It should also away from areas with a lot of foot traffic, otherwise a busy bee might crash into you as she travels back and forth while building her nest.

The nesting boxes should not be easily accessible by predators and scavengers, such as birds, raccoons, squirrels, and other rodents. Do not place these next to a bird feeder, which could attract other critters and give them easy access to the bee larvae.

Aftercare

Another common error made with bee hotels is forgetting the aftercare involved with these nesting structures. Because these nesting structures create a more ‘artificial’ nesting environment, grouping a large number of nesting locations in a concentrated area creates a different from what bees have historically utilized in areas with large expanses of natural habitat. If left unmanaged these structures can act as refuges for pests and disease which can be detrimental to the bees that nest in them. This can be counterproductive for our efforts to protect and preserve these pollinators. If you are interested in hosting cavity nesting bees in your home gardens year after year I would strongly encourage you to learn more about aftercare

If you do intend to place bee hotels in your home gardens, here are some very basic aftercare tips to follow, in order to keep these structures a safe and useful nesting option for cavity nesting solitary bees in urbanized areas.

– Move the occupied nesting structures of these bee hotels to a safe outdoor location in the fall, such as an unheated shed or garage, to protect overwintering bees from rodents, other scavengers, and harsh winter conditions. You can also keep these in a wire mesh/ventilated container to further protect them from rodents chewing them.

– Adult bees emerge from these tubes in spring and early summer, so these should be placed back outside when spring temperatures warm up to around 50°F (10° C). After bees have emerged, discard/compost used tubes and discard/burn used drilled blocks, so pest and disease pressures don’t build up.

– Refill your nesting box with new tubes, reeds/twigs, and drilled wooden blocks for the next season of bees to use, and enjoy watching the process all over again!

For more detailed information on caring for the bees in nesting boxes, please take a look at the resources below.

Resources:

- Building and managing bee hotels for wild bees

- Creating a solitary bee hotel

- Creating pollinator habitat

- Nesting and overwintering habitat for pollinators & other beneficial insects

- Nurturing mason bees in your backyard in Western Oregon

Hi Ms. Saeed, Thank you so much for this informative article. It so happens that the day I read it, yesterday, I had also come across the concept of pollinator palaces, which are stacked old metal milk crates or something like that, and can be part of a landscape design.

One of the things one of the writers specified is that bamboo tubes were found to splinter on the inside and harm the hatchling bees on their way out. Your article does recommend bamboo. Do you know if it’s safe? I’d like to be very certain about materials to use.

I am an environmental writer and I love sharing ideas on ways to help our declining planet. And I love the articles I find here on Garden Professors! Thank you! And thank you for the resources at the bottom of the article.

Hi Doreen, and thanks so much for your comment! From what I have read, the primary concerns pertaining to using bamboo tubes (or any other nesting material for that matter) are to do with increased pest and disease pressures through concentrating several nesting sites together and/or reusing materials. I have not seen research on bamboo tubes splintering and hurting hatchling bees, but I will look more into this. If you have resources to share, I would love to see them as well!

My best recommendations for the exact types of materials to use would be to make a cavity nesting area resemble what can be found in nature: leaving hollow, pithy stems in your garden in the spring and old wood piles with existing holes, etc. Since space is often a restriction, and doing this is not feasible for many- artificial nesting structures that meet the size/depth requirements (whether they are made with bamboo, cardboard, or wooden blocks) can also offer this habitat. The most important consideration would be to clean out these bee hotels annually, and discard/replace any nesting materials to limit pest/disease buildup.

Thanks for reading!

I simply just pickup logs from around the neighborhood and bury them in the ground, much like a stump, and allow the bees to make their own nests.