Like many readers of this blog, I’m like a kid in a candy store where plants are sold. I try to justify the extra cost of a large annual pot instead of a scrawny 4-pack, or I imagine I’ll find room for that lime green Heuchera and my wife will learn to love it. But unless I keep my blinders on and stick to the shopping list, I’ll probably leave with a fertilizer. This year, I’ve purchased 12-0-0, 5-6-6, sulfur, and some 5-1-1 liquid. Those go with my 6-9-0, 11-2-2, 9-0-5, 2-3-1, and 4-6-4. I can explain why I ‘need’ each one. I have a decent idea what my soil is like because I’ve had it tested (though I’m due for another test). But I’ve always questioned how those bags of fertilizer can know exactly what my garden needs. The rates listed on the bag imply they’re universal under all circumstances and will give great results if the directions are followed. Is that true? And at what cost?

For example, 2 of the bags are listed as ‘lawn’ fertilizers (the veggie garden doesn’t care about that though). But if I apply these to my lawn at the rate listed and 4 times per year, I’m adding 3-4 pounds of nitrogen per 1000 ft2. That’s a reasonable rate if I irrigate and bag my clippings, but I don’t do either. Therefore, I only need ~1 pound of nitrogen, not 3 or 4 (see this publication for more info). I just saved myself some money by disobeying the bag. That extra nitrogen isn’t useful for making MY lawn healthy.

One of my fertilizers is labeled ‘tomato’. If I do exactly as the bag tells me for tomatoes, I would be applying the equivalent of 400 pounds of nitrogen and almost 500 pounds of phosphate per acre. So what? Well if I look at a guide for how to grow tomatoes commercially, I’d notice that the recommended nitrogen rate is 100 to 120 pounds per acre, and phosphate is 0 to 240 pounds per acre. Yes, those are commercial guidelines, but they shouldn’t be too far off from garden recommendations. And of course, recommendations should always be based on soil tests. But 4 times the N and 2 to infinitely more times the amount of phosphate than is required? That’s likely a waste of money at least. And yes, those recommended guidelines are real: you CAN grow food without adding phosphate or potassium-containing fertilizers. If the plants you’re growing don’t need much and your soil has plenty, you don’t need to add any.

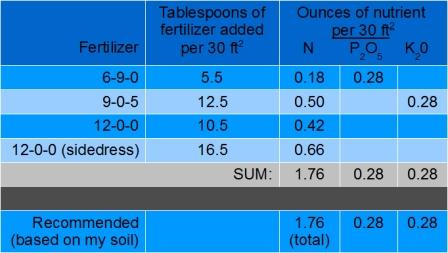

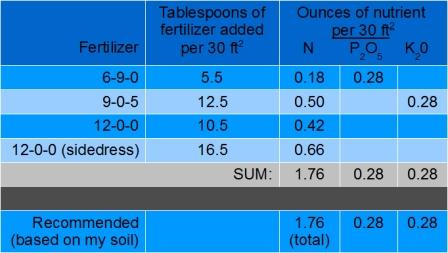

Say I’ve got an acre of onions (Fig. 1; not quite an acre). One of the bags of fertilizers, were I to follow its instructions for fertilizing ‘vegetables’, tells me that I should add 100 pounds of nitrogen and 120 pounds of phosphate and potash at planting (per acre), followed by half that partway through the season (next to the row). The commercial production guidelines tell me that the nitrogen rate is similar to what the bag of ‘vegetable’ fertilizer says, but I actually need about 7 times less phosphate and potash (based on my soil test results; I have quite a bit of P and K already in my clay-loam soil). I don’t want to add stuff my soil doesn’t need, so I use my shelf full of bags, a scale for weighing pounds of fertilizer per cup, and some math to come up with a custom fertilizer regime that suits my soil and the onion’s needs (see Table 1, and remember that the numbers are for MY soil, not necessarily yours).

One problem with using extra fertilizer may be in the extra cost (wasting nutrient the plant won’t use), but that depends on what fertilizer it is and how much it costs. Another problem may not be immediately apparent, and that is nutrient deficiencies. Too much phosphorus can cause zinc deficiencies, for example. Excesses of some nutrients can create greater chances for pest and disease problems. One big problem with using too much is the potential for these extra nutrients to go where they shouldn’t be, like in groundwater, rivers, lakes, and streams. And as Jeff has mentioned, phosphorus fertilizers won’t be around (cheaply) forever.

Do the work of figuring out what kind of soil you have and what’s in it, what your fruits and veggies need, and what kinds of fertilizers can do the job for you. Heck, you can even organize your fertilizers based on “cost per pound of nitrogen” to see where the best bang for your nitrogen buck will be. But none of us are THAT obsessed about our fertilizers, right?…. [$ per bag / (pounds per bag * (% nitrogen/100))].

As a reminder, the numbers on your fertilizers are percent nitrogen, phosphorous (as ‘phosphate’, P2O5), and potassium (as ‘potash’, K2O). One cup is 16 tablespoons, and an acre is has length of one furlong (660 feet) and width of one chain (66 feet), or 43,560 square feet. Side rant: metric rocks.