As we edge closer to spring it is time to start getting ready for the active growing season. Many gardeners kick off their gardening year early with indoor seed starting to prepare for the upcoming season.

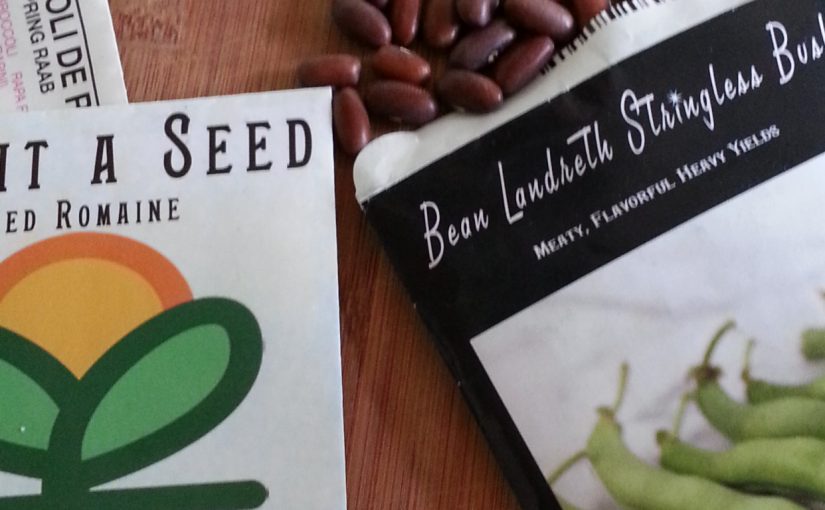

Starting your own seeds is an excellent, and often economical way to prepare for your year of gardening. Whether you grow vegetables or flowers (or both), starting from seeds can offer many benefits. Of course, there are some dos and don’ts for getting the most mileage from your seed starting endeavors.

I recently connected with Joe Lamp’l, host of the Growing a Greener World show on public television and the more recent The Joe Gardener Show podcast to talk about advanced seed starting techniques and technology.

I recently connected with Joe Lamp’l, host of the Growing a Greener World show on public television and the more recent The Joe Gardener Show podcast to talk about advanced seed starting techniques and technology.

You can follow the link below to listen to the show on your computer, or find it on Stitcher or iTunes (links included on the show page, too). In addition to the podcast, the show page features extension notes on everything we chatted about with links to good reading materials.

Seed Starting Indoors: The Joe Gardener Show featuring GP John Porter

Here are a few of my best seed starting tips:

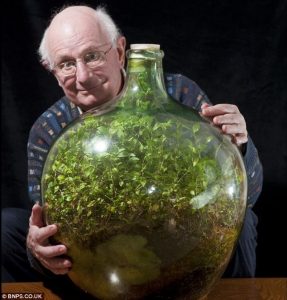

- Be economical. One of the great benefits of starting plants from seeds is saving money. A packet of several (even hundreds) of seeds is often around the same price you’ll pay for one plant at the garden center. Of course, if you go out and splurge on the fancy (and expensive) seed-starting systems you see in your garden store or favorite catalog you may end up investing more than you planned. Instead of fancy seed starting trays or peat pellets and pots, use low-cost or recycled items such as takeout containers or shallow disposable aluminum baking pans to start your plants. Remember that if you are reusing containers, especially ones that have had plants grown in them before, that sterilization is key in reducing disease. Thoroughly wash the containers, then dip in a solution of 10% household bleach (1 part bleach : 9 parts water) to disinfect. There are some horticultural disinfectants out there, but bleach is usually the easiest for home gardeners to get since you can pick it up at the local store.

- Start seeds in clean, sterile seed-starting mix. This is one area where I don’t skimp. You’ll want to use a sterile mix that is primarily made of peat or coconut coir. It is lightweight and pathogen free and also low in fertility, so you will be less likely to lose plants to such issues as damping off (a fungus that rots the seedlings off at the base). Using regular potting mix may work, but increases your chances of such issues. Plus, seeds are equipped with enough nutrients to make it to their first set of true leaves before they need anything from the soil. I know that some sources say to use mixes with compost in them, but unless you know 100% that the compost got hot enough to kill all pathogens (140 degrees plus for several days) you could be introducing diseases to your plants that could affect them in the seedling stage or in the future.

- Once the seedling has its first set of true leaves (the second leaves that appear), you should transfer it to an individual container/cell/pot with regular potting soil. At this point, the plant will need to have nutrients from the soil to grow healthy. You’ll want to loosen the plant from the seedling mix (I use a chopstick) and lift it by the leaves (not the stem). Temperature control is key.

- Heat is usually the most important factor in coaxing your seeds to germinate, so placing your newly sown seeds in a warm (around 75 degrees F) place will help them germinate faster. Fast germination is key for making sure you get the optimal number of seeds sprouting. However, moving the seedlings to a cooler place (around 65 degrees) after they’re germinated will make them grow sturdier and keep them from getting thin and leggy. Most people laugh when I tell them, but one great warm place to start seeds is on top of the refrigerator.

- Light is necessary for good plant growth. Most seeds don’t require light until they get their first true leaves, but after that you’ll want light to keep your plant healthy. Some people are lucky to have a good, sunny (usually south facing) window with plenty of light. Otherwise you’ll need to invest in some lighting. The most economical option is a basic shop light fixture from the hardware store. You can buy plant lights, or full spectrum lamps for it, but if they prove too difficult (or expensive) to find, use a regular warm fluorescent and cool fluorescent bulb to get the right light spectra. You’ll want light on for about 16 hours per day. If you are using a window, be sure to turn the plants regularly to keep them from

Blue and Red LEDs Source: Wikimedia Commons growing in one direction. As LED lights become less expensive, many home gardeners are checking them out for home seed starting. You can use a full spectrum white LED bank, but plants primarily use red and blue light so you can also find high-intensity LED banks for plant production that are blue and red (makes purple!). Some research is emerging that a tiny bit of green light helps growth, so some newer systems are incorporating a touch of green, too.

- Don’t get started too early. Look at the packet for the number of days/weeks before last frost to start your seeds. If you start them too early, you could end up with spindly, leggy plants or ones that have grown too large for their containers. Even if you have good lighting, your plants will not thrive being cooped up in the house too long.

- What about fertilizer? Up until the first set of true leaves, seedlings don’t need much in the way of fertility. When they’re put in larger containers or cells, a good potting mix (usually containing some type of fertilizer or nutrients) will get you most everything you need….to a point. If you’re growing in small containers, say those cell packs where you have very limited soil, you may find that you need to provide supplemental fertility after a few weeks. There’s only so many nutrients in that potting mix in small amounts, so if you are holding your plants for longer than, say, six weeks you may need to apply a water-soluble fertilizer or start off with a slow-release fertilizer. Larger containers, say a 3 or 4 inch pot, may have enough soil to have sufficient nutrients to get you to the point of transplanting.

“Certified organic” means that the producers practices have been certified to meet the requirements laid down by a certifying agency. A certifying agency could be a non-profit or a state department of agriculture. The requirements and practices vary from entity to entity.

“Certified organic” means that the producers practices have been certified to meet the requirements laid down by a certifying agency. A certifying agency could be a non-profit or a state department of agriculture. The requirements and practices vary from entity to entity. “

“