You may have heard about these fungi or perhaps not. But if you look carefully on bags of potting mix and on some fertilizers you will see that they are marketed as “essential” to your garden plants. Claims on mycorrhizal products suggest dramatic growth increases. These claims like many “snake oil” products can be extreme and are based on science that supposedly bolsters their efficacy. Mycorrhize are responsible for tremendous growth increased when compared to plants denied access to the fungi. This has been known for many decades.

The disconnect between mycorrhizal claims and garden efficacy is that there are usually mycorrhizae present in most gardens. So adding more won’t necessarily improve the growth of plants. There are also some other concerns. Mycorrhizal products are not all the same. Research on product efficacy suggests that about half the retail products available contain no viable inoculum. Spores of mycorrhizae have poor germination viability and do not last long on the shelf although some products contain hyphae as well as spores and these may last longer. So even though products are out there they might not not infect plants.

While mycorrhizal products may or may not hold value for gardeners, mycorrhizal fungi are essential for almost all plants. A few, such as brassicas, do not form mycorrhizal partnerships but all trees, other woody plants and most annuals do become infected by and benefit from these fungi. Plants and mycorrhizal fungi are symbiotic and each receive reciprocal benefits when each partner is well established.

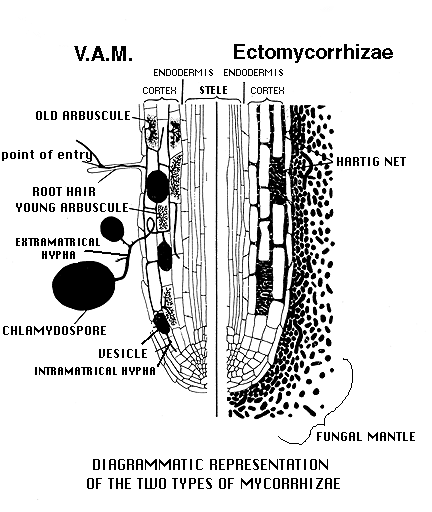

There are two broad categories of mycorrhizal fungi the VA (formerly VAM) or vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae and the ectomycorrhizae, (EM). VA mycorrhizae are fungi in the class Zygomycetes related to the common bread mold fungus. They inhabit 80% of the worlds plants. They can not be seen without staining and careful microscopy. Ectomycorrhizae are the other form and they are exclusively from the Basidiomycete or mushroom forming class of fungi. Many of the mushrooms that grow in forests are actually supported by tree roots they affiliate with. Ectomycorrhizae change the shape of roots giving them a stubby appearance. This is because ectomycorrhizae form a mantle around the root of hyphae called the Hartig Net.

So why the big deal? What are the benefits that plants share with mycorrhizae and how do the fungi benefit from their plant hosts? Early studies showed that mycorrhizae make minerals, especially phosphorus, more available to their plant partners. Studies show that mycorrhizae increase the efficiency which plants use many fertilizer elements, even nitrogen. Fungi become “sinks” for plant carbohydrate or sugar. Mycorrhizal hyphae replace root hairs in most infected plants and vastly increase the surface area of roots. This gives roots the ability to withdraw water from very dry soils since mycorrhize can access water held at higher pressures on soil particles than roots can. Thus mycorrhizae infected plants especially with EM, have greater drought tolerance.

Mycorrhizae are an integral part of the carbon cycle on earth and are the reason why there is roughly 2X the amount of carbon stored in soil than in all the plants growing above the soil. This is because up to 20% of plant photosynthate is excreted into soil as a stable polymer called glomalin. Glomalin is responsible for binding soil particles and creating micro-aggregates and soil with water soluble aggregates does all kinds of good stuff. It increases soil moisture holding capacity while improving porosity and drainage. All of this helps reduce root rot hazard.

Mycorrhizae also affiliate with microbes. The hyphae of mycorrhizae cultivate bacteria which produce antibiotics that protect the host plant from pathogens. Linderman coined the term mycorrhizosphere to describe the microbial community that affiliates with these fungi. Plants are also protected by the Hartig net of EM mycorrhizae because it provides a shield or barrier so that pathogens have a difficult time invading the plant root. So, mycorrhizae greatly benefit plants by defending their roots from pathogens.

How do we keep the mycorrhizae growing with our garden plants? Most gardens are well inoculated with mycorrhizae at least the AM kinds. To get more access to EM it is necessary to also provide the organic carbon that they affiliate with. While EM absorb sugar from plant roots, their hyphae also grow into woody mulches helping to solubulize the nutrients contained in mulch and bring them back to their tree hosts. The litter and woody debris that fall in forests (litterfall) are essential for these organisms. We can simulate litterfall in gardens by applying fresh arborist chips and nourish the EM fungi as well as our woody garden plants at the same time.

References

Corkidi, L., Allen, E.B., Merhaut, D., Allen, M.F., Downer, J., Bohn, J. and Evans, M. 2004. Assessing the infectivity of commercial mycorrhizal inoculants in plant nursery conditions. J. Environmental Horticulture 22:149-154

Corkidi, L. Allen, E.B., Merhaut, D., Allen, M.F., Downer, J., Bohn, J and Evans, M. 2005. Effectiveness of four commercial mycorrhizal inoculants on the growth of Liquidambar styraciflua in plant nursery conditions

Linderman, R.G. 2005. Bio-based strategies for the management of soilborne pathogens. Presented at the Landscape Disease Symposium, University of California, Santa Paula.

Linderman RG. 1988. Mycorrhizal interactions with the rhizosphere microflora: The mycorrhizosphere effect. Phytopathology 78:366-371.