As a lover of the weird and wonderful, October is one of my favorite months of the year, because of Spooky Season. To celebrate, I thought it would be fun to learn about some of the weird and wonderful plants around us, especially some of the most notorious: carnivorous plants.

Whether you like to grow them, observe them in their natural habitats, or simply just learn about them, it’s easy to understand our collective fascination with carnivorous plants. Many of us may have seen depictions of ‘man-eating plants’ in horror movies, or exaggerated tales of some of these killer plants in fictional stories, cartoons, and other pop culture references. The horror genre’s elaborate and embellished portrayals of carnivorous plants were inspired by Charles Darwin, before which plants were considered to be innocent bystanders to the ecological phenomena surrounding them. Having spent 16 years researching carnivorous plants, Darwin published multiple books about them. This shifted our perception of plants as a whole and how they interacted with other organisms, giving rise to our fascination with carnivorous plants, driving our desire to understand their biology, and fueling our creativity by exaggerating some of these adaptations into very entertaining science fiction. I wonder If he could have ever imagined the creative ways in which popular culture (especially science fiction and horror) would go on to embrace these botanical marvels.

Types of Carnivorous Plants

Carnivorous plants are defined as plants that extract nutrients from animals. These plants have a variety of adaptations that allow them to capture and/or trap prey (most often insects and other arthropods), and enzymes that can break this prey down into nutrients that can be used by the plants themselves. Although carnivorous plants do still perform photosynthesis, they get most of their nutrients from captured prey.

Some of the more famous carnivorous plants include the charismatic Venus fly trap (Dionaea muscipula), the North American native pitcher plants (Sarracenia spp.), the tropical vining pitcher plants (Nepenthes spp.), the widespread sundews (Drosera spp.) and butterworts (Pinguicula spp.), and the moisture-loving and often aquatic bladderworts (Utricularia spp.). Some not as well-known examples include a few species of carnivorous Bromeliads (in the genera Brocchinia and Catopsis), and Triphyophyllum peltatum that can become carnivorous in situations of nutrient scarcity, after which it may revert to a non-carnivorous lifestyle. There is also a plant called the Gorgon’s Dewstick (Roridula gorgonia) which captures insects, but lacks the mechanism to digest this captured prey. Instead, this fascinating plant will trap this prey to attract the jumping tree bug (Pamerida spp.) which feeds on these trapped insects, while leaving nutrient-rich frass (insect poop) which is absorbed by the leaves of this plant!

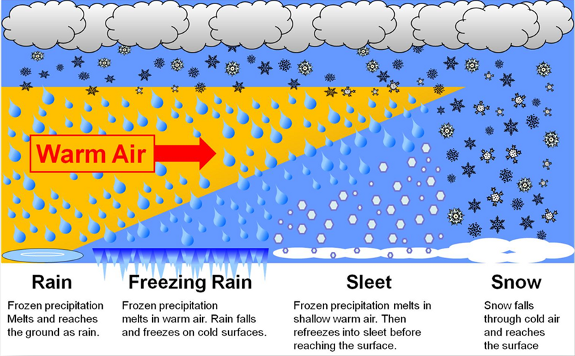

The ways that plants actually capture their prey are pretty diverse: ranging from sticky substances that can immobilize prey, dark tubes and funnels that can trap and disorient them, and mechanical methods that can snap/ensnare or suction prey, dooming them to their fate. These mechanisms are defined as ‘active’ or ‘passive’ based on whether there is movement involved in the prey-capture process.

Evolution of Carnivory in Plants

Although we previously lacked a deeper understanding, advancements in molecular biology have allowed us to paint a more complete picture regarding how plants actually evolved this interesting adaptation.

Carnivory in plants is another classic example of convergent evolution (where unrelated species independently evolve similar traits), with instances of its occurrence over 12 different occasions across the evolutionary timescale of flowering plants (angiosperms). We currently estimate that carnivory is evident in over 800 species of plants across more than a dozen plant families.

All of these instances of carnivory were driven by similar needs: limited nutrient availability in the habitats in which these plants grow. These carnivorous plants grow in conditions which lack specific nutrients essential for plant growth (many of which include bodies of water or soils that are low in Nitrogen and Phosphorous). Arthropods such as insects can be excellent sources of these (and other) essential nutrients, and are often abundant in these habitats…all that plants needed to do was to come up with a way to tap into this great resource. They were able to accomplish this by repurposing existing genes to capture these six- and eight-legged snacks, and extract the nutrients found within them. Researchers who evaluated the digestive enzymes found in these plants noticed that there were quite a few similarities between these and defensive chemicals used by ancient flowering plants to protect themselves from pathogens and pests. Most carnivorous plants use similar enzymes including chitinases, proteases, and acid phosphatases (all of which have roles to play in the breakdown, dissolution, and absorption of nutrients from the corpses of their arthropod prey). In an interesting evolutionary twist, these chemicals were repurposed to eat some of the pests that they were originally protecting the plants from! How cool is that?!

If you want to learn more about the evolution of plant carnivory, I recommend reading the wonderful Smithsonian article linked in the resources below.

Carnivorous Plants and their Pollinators

With plants that have evolved to kill and consume arthropods, one can’t help but think about the pollinators that they depend on. How can plants attract both prey and pollinators? How do they go about selectively capturing the ones that they kill and extract nutrients from, while also protecting the ones that they rely on for pollination?

Insect and plant relationships can be multi-faceted, interesting, and extremely sophisticated (and plant/pollinator interactions are arguably some of the most interesting of these). Carnivorous plants have come up with ways to navigate this ‘pollinator-prey conflict’ utilizing a few main mechanisms. These include separation of the traps from the flowers, which is either done temporally or spatially. Some carnivorous plants will bloom before the traps have developed, allowing them to be successfully pollinated before they begin capturing prey, while other plants may physically separate the flowers from the traps themselves, often positioning flowers much higher than the traps which would be found closer to the ground (the method used by the Venus Fly Trap). They may also use different attractants (such as odors and colors) in their flowers and their traps to attract specific pollinators to flowers and only prey to traps; or they may use a combination of the aforementioned strategies.

Growing Carnivorous Plants

Although many carnivorous plants can have complex growing requirements that can make them difficult to grow in captivity, there are quite a few plants that are well-suited to this. Furthermore, we all know some very ingenious gardeners that can grow some of the trickiest plants with ease, laughing in the face of what others may consider ‘impossible’! My mother is a classic example of one of these gardening goddesses who manages to propagate and grow some of the most ‘difficult’ plants, often the ones that I have told her will probably not be successful. To those of you who are like my mother, I salute you. For the rest of us, I will focus on some carnivorous plants that are more user-friendly.

There are a variety of carnivorous plants that grow well indoors, and several available resources to help troubleshoot growing requirements (including a variety of websites and blogs that are dedicated to carnivorous plants, some of which I have included in the resources below). For beginner-friendly carnivorous plants, I would recommend starting with Venus fly traps and sundews. Often far less fussy than most, these are sometimes considered ‘gateway’ plants for those who might be starting out on their carnivorous plant journey. Tropical pitcher plants (Nepenthes spp.) are another popular houseplant choice, and these vining beauties can be attractive additions to your carnivorous collection.

There are also a few carnivorous plants that can grow well in outdoor gardens as long as the appropriate conditions are present. The purple pitcher plant (Sarracenia purpurea) is an example of a cold-hardy carnivorous plant that is especially suited to growing outdoors in North America (in USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 3-8), but there are also other temperate species of carnivorous plants that grow well in outdoor gardens in other temperate regions, and tropical carnivorous plants that are better suited to growing in more tropical regions. The most common carnivorous plants grown in outdoor gardens include temperate pitcher plants (Sarracenia spp.), sundews, and the Venus fly trap. I encourage you to look into the carnivorous plants of your region to see what could possibly grow in your home gardens. Note: you should never remove native plants from their native landscapes, because this could damage some of the fragile ecosystems in which they reside. Instead, source suitable plants from reputable suppliers who grow and propagate them sustainably.

Like any plant growing recommendations, there is never a one-size-fits-all approach to caring for carnivorous plants, nor are there plants that work well in every single situation. One of the keys to growing carnivorous plants is to make sure that you are providing these plants the right kind of growing conditions for them to thrive, often mimicking the conditions in which they thrive in nature. Most of these carnivorous plants need bright light, and supplemental lighting may be necessary if you don’t have a suitable location with access to enough sunlight. They also need lots of mineral-free water (many use distilled water for this), and nutrient-poor soils. You can even purchase carnivorous plant-specific soil mixes to simplify this process. Humidity is another consideration, and humidifiers, misting, or using terraria that can maintain humid conditions may be necessary. These plants don’t need to be fertilized, and it is important not to overfeed them. Indoor plants can be fed one or two insects per month (don’t feed them meat), whereas outdoor plants will probably not need to be intentionally fed, (as they can often get their insect nutrient sources on their own), but make sure they are grown in a location that has access to insect prey.

(If you are a carnivorous plant caretaker, what are some of your favorites to grow?)

More Information:

Carnivorous Plants (Penn State University):

https://extension.psu.edu/carnivorous-plants

How Carnivorous Plants Evolved:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/how-carnivorous-plants-evolved-180979697/

El-Sayed, A., Byers, J. & Suckling, D. Pollinator-prey conflicts in carnivorous plants: When flower and trap properties mean life or death. Sci Rep 6, 21065 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21065

Some Resources for Growing Carnivorous Plants:

https://carnivorousplantnursery.com/blogs/cpn-blog

https://www.carnivorousplants.org

https://tomscarnivores.com/blog/start-here