Things have settled down briefly here and I have had a chance to summarize some of the data from the container tree transplanting experiment we installed earlier this year. For those that aren’t familiar we installed two tests this summer using 96 ‘Bloodgood’ plane trees grown in 25 gallon containers that were leftover when we completed an earlier trial in our Pot-in-Pot nursery. I decided to use this as an opportunity to look at some tree transplanting recommendations. With input of our GP blog readers, we installed two tests. In both tests we applied three treatments to the tree root-balls before planting (‘shaving’ the outer roots to eliminate girdling roots; ‘teasing’ apart the rootball to eliminate girdling roots, and a control or ‘pop and drop’ to use Linda’s nomenclature). At one site we fertilized half the trees at planting and left the others unfertilized. At the second site we mulched half the trees with 3” of ground pine bark and left the others unmulched.

On the fertilizer trial we have not seen anything remarkable. We conducted measurements of leaf chlorophyll content using a SPAD meter (a device that measures light transmittance through leaves) but did not see an effect of either fertilizer or root ball treatments. This is not completely surprising. In the nursery trial we fertilized the trees at standard production levels, so their nutrient status was pretty good at the outset. What will be interesting is to see if either treatment at planting has a longer term impact.

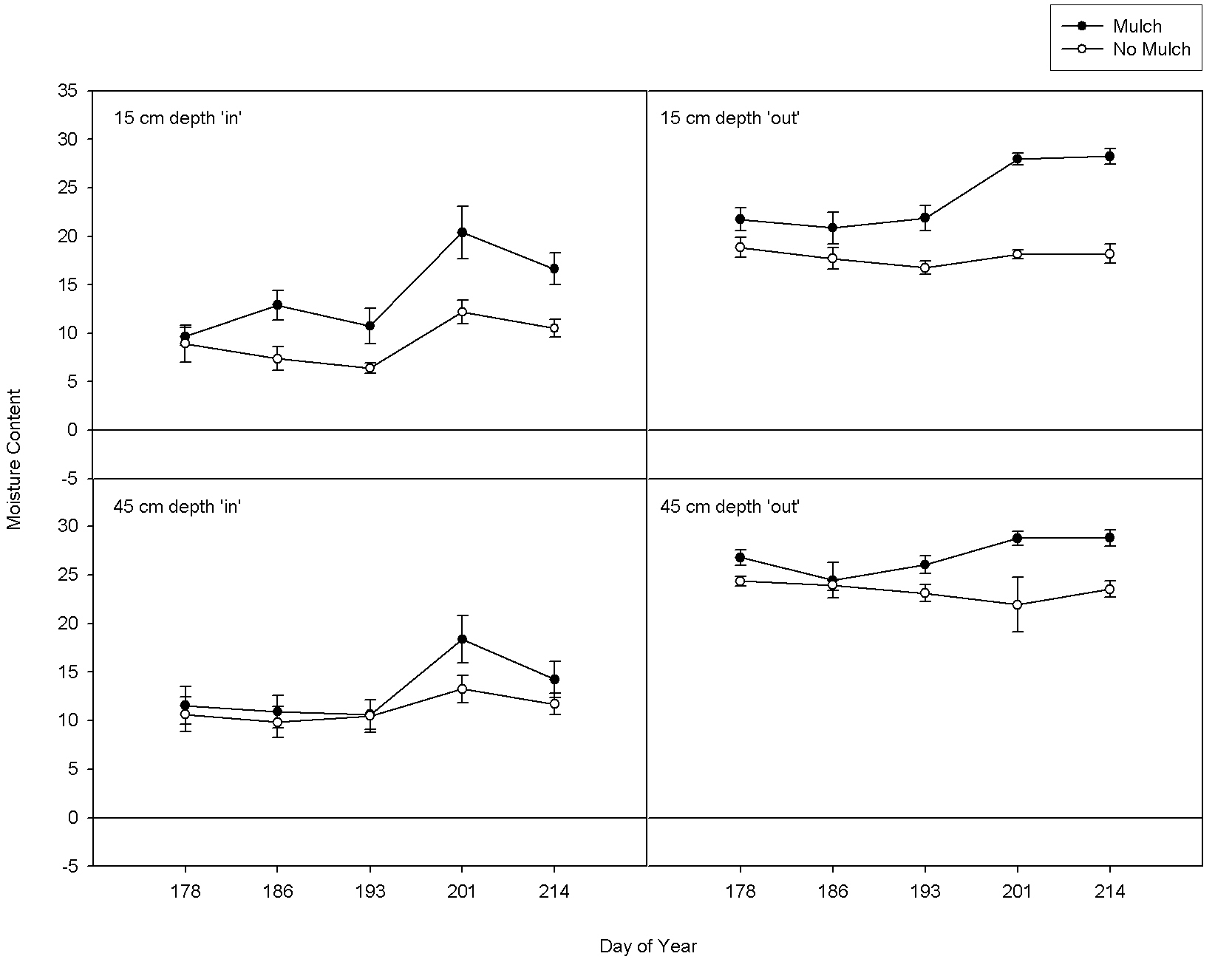

In the mulch study we have seen some more immediate impacts. We measured soil moisture to 15 cm (6”) and 45 cm (18”) inside the rootball and just outside the rootball periodically during the summer. Soil moisture levels were consistently higher for the mulched trees that for the trees that were not mulched (Fig. 1), especially at the shallow (15 cm) depth.

Figure 1. Soil moisture of trees with and without mulch in the SoMeDedTrees study, summer 2012. (Sigmaplot wizardry by Dana Ellison)

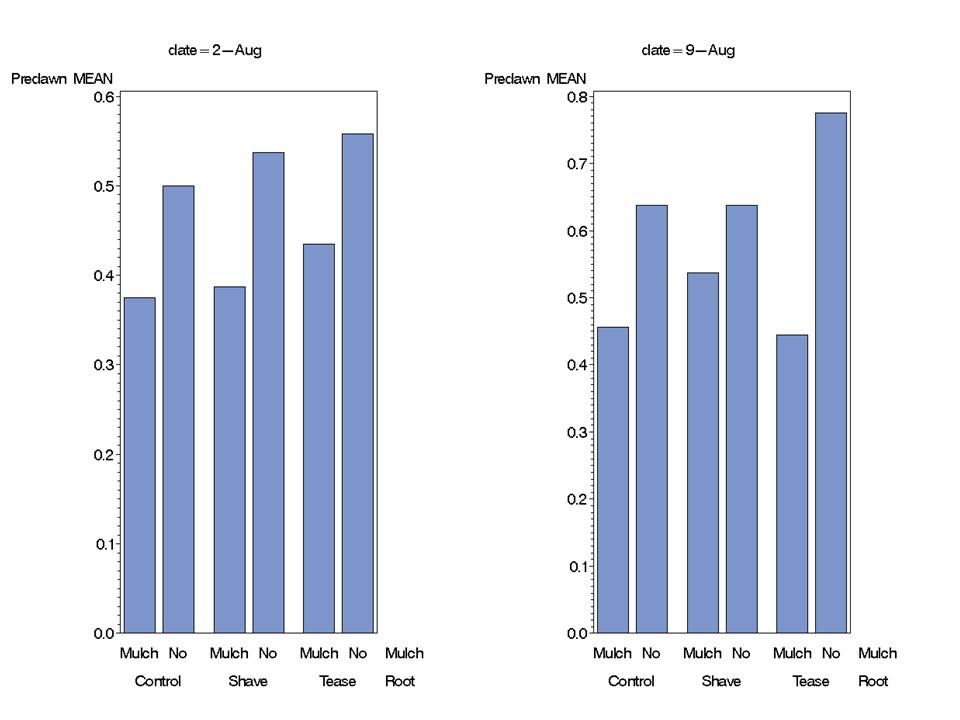

This was reflected in tree moisture stress levels during August. We measured predawn water potential with a pressure chamber. Using a pressure chamber enables us to estimate the level of tension with which water is being held inside a tree. We remove a leaf from the tree and put it in a chamber with the cut end sticking out. We gradually increase the pressure in the chamber until we see water appear on the cut end. The more stress the tree is under the more pressure we have to apply to get water back out. In this case, mulching, by virtue of the fact it increased soil moisture, resulted in lower water potential values, indicating less stress (fig. 2). The root ball manipulation treatments, on the other hand, did not affect tree stress.

Figure 2. Mean pre-dawn water potential (in -MPa) of plane trees in the SoMeDedTrees study, August 2012.

So where does that leave us? Well, as we’ve noted all along, this is long-term trial. The plan is to track the trees over 3-5 years and maybe longer. But long-term responses are the cumulative results of series of shorter-term effects. So far, mulching appears to be the only factor that has made a difference but we are still early in the game.