Last week’s column on “why do nurseries sell this plant?” struck a chord with many readers as well as with Holly! So here is this week’s submission: that ubiquitous vine, English ivy.

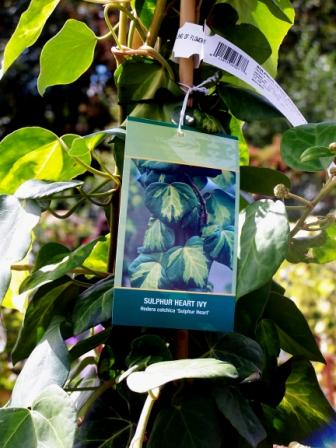

First of all, we’ll stipulate than many ivies are sold as English ivy (Hedera helix) but may be entirely different species. Genetic research on invasive ivy populations in the Pacific Northwest identify most as H. hibernica (aka Atlantic ivy), with H. helix making up only 15% of the invading populations. Regardless of their species identity, it’s obvious that Hedera is a genus with the potential to escape gardens and invade remnant forests or other environmentally sensitive areas. It grows so vigorously that it can create monocultural mats on forest floors; it grows into trees where its sheer weight can break limbs and in some cases topple entire trees.

But what about other regions of the country – or the world, for that matter? In colder climates, Hedera spp. are much better behaved, dying back to the ground every winter and rarely able to flower and reproduce. The absence of a seed bank means the vine can be kept in check more easily. And it does tolerate tough environmental conditions where other groundcovers might not succeed.

Yet consider another invasive: kudzu (Pueraria montana var. lobata) For decades this noxious weed was thought to be too cold sensitive to expand past the American Southeast. Yet populations have been found in Maine, Oregon, and most recently in Ontario, Canada. Plants adapt!

So – is it worth the risk to buy a plant known to be invasive elsewhere, simply because it’s not a problem yet?

And why oh why do nurseries in Washington state continue to sell Hedera spp. as ornamentals?

English Ivy or Irish Ivy (Hibernia was the Latin term for Ireland), they sell it because people buy it. The key is to educate people on the dangers of ivy, as you are doing.

My plant peeve right now is sedum. It’s used and promoted extensively for green roofs and rooftop garden use, because it grows so well in extreme conditions — which makes it also quite willing to grow in not-so-extreme conditions. I planted a handful that a neighbor had given me, and it now has spread through one garden bed, along the base of a rock outcrop on the other side of the yard (I took a snippet and parked it from the bed onto the outcrop, not knowing how it would spread and spread), and now is moving into the lawn. It’s easy to pull out, but a tiny piece will root, so composting is out, and vigilant disposal is necessary. I have yet to see sedum on an invasive species list, but predict that it will show up on a bunch of them in the next few years, as pieces make their way off of rooftops and into the on-the-ground landscape.

Don’t believe it if you are told that some particular cultivar is not invasive. After living peaceably in my garden for 10 years, my variegated ivy made a break to escape. It took a lot of effort to subdue it.

Sneaky little devils, aren’t they VG? Some plants need a lag period before they take off – sometimes many decades. Fascinating stuff.

I live in Lakewood, WA – where I tremble in fear as I survey the very tall trees covered with ivy surrounding our property (much like the photo posted). My partner and I deal with our own trees, but we can’t compel our neighbors to do so!

And, I also know Sedum quite well. Our property belonged to my partner’s parents, who gardened/landscaped here for 30 years. My mother-in-law experimented with every ground cover ever sold over the years – I’m drowning in the stuff. We have Gentiana that is taking over and killing a small, weeping type of conifer tree…its a kind of “Groundcover Apocalypse” around here. Too bad you can’t eat the stuff.

Also, regarding invasive vines…I also have a type of invasive Japanese vine to contend with. My late mother in law was born in Japan – I think the plant in question is grown for its root, which is used in Japanese cooking. Anyhow, its not as bad as the ivy, but shows up from one end to the other of our one acre yard.

Invasive groundcover Sedum? That’s a new one for me. Which varieties and/or cultivars are invasive and in what part of the country? And I mean truly invasive, not just inconveniently aggressive.

The designation as invasive has grown so common that, to my mind, the word is only useful if the state DEP or Dept of Agriculture takes regulatory action. Growers will continue providing any popular plant that isn’t regulated.And regulation is not in anyone’s best interest until a plant has proved dangerous to an ecosystem. Someone with expertise has to define that and then follow up with regulatory power. Nice-to-do only nudges a few to action.

Bernadette, that’s the problem: invasion biologists have defined the problem, many states have invasive species policies, but there is little enforcement. And in terms of the nursery industry, much of the regulatory policy is advisory. As long as the industry refuses to see the bigger picture, we’ll continue to see inappropriate species for sale.

English ivy is an ideal plant in New Mexico. It can survive without irrigation in the mountains, and it makes a nice groundcover under a tree, cooling the roots…but if it ventures out from the shade, it gets scorched so badly it dies. It also isn’t very vigorous as a climber at all there. It doesn’t get very far up a tree–I’m guessing the winter is too punishing.

Different plants react differently to different climates. You would be restricted only to very, very local natives is you play the “what if” game with everything. When I first moved here, I was flabbergasted that English ivy could be considered invasive at all. Thanks to bird poop, I’ve learned!