About 3 months after I started my job in Minnesota I hired a technician to help me run the nursery and to manage research plots. His name is Chad and he stands about 6 foot 4, has shoulders that threaten to pop the sides of the skid steer loader whenever he enters it, and he knows his stuff because he needs to (and even if he didn’t know his stuff you’d be scared to tell him that because he looks dangerous with his frightening Fu-Manchu moustache). Currently Chad is responsible for day to day operations in the nursery as well as writing publications. In other words he’s indispensible. When you read a post from me, particularly when it’s regarding nursery or landscape research, you’re usually reading a combination of both of our thoughts.

Over the years Chad and I have seen a lot of nursery stock; some of it good, and some of it bad. Between us we’ve seen poor pruning, unhealthy root systems, pot-bound plants, trees planted in soil that was much too alkaline or acidic for them, trees planted in the wrong zone, trees sold that weren’t close to the size that they were supposed to be, trees that were girdled by critters, root systems completely eaten by voles and even a tree shot with a handgun. I once saw a whole field of Japanese maples topped (basically topping is when you cut horizontally through a trees canopy to give it a flattop – talk about competing leaders and narrow crotch angles!). Seeing that field almost made me cry – A planting worth $20,000 – $30,000 wholesale almost instantly became worth the price of kindling. But we agree that none of that can hold a candle to Sara’s Nursery (Named after the owner’s daughter).

I received a call a few years ago from a nursery in western Wisconsin (which, for those of you who aren’t familiar with this part of the world, is much closer to the Twin Cities than to Madison, WI where the University of Wisconsin is). The caller was very concerned that the plants in the nursery which she had been hired to run were failing. Basically, their leaves were dropping and she couldn’t figure out why. This was even happening to plants that we usually consider “indestructible” like potentilla. I had never heard of such a thing, but it sounded like a soil problem and so I asked her to have some soil tests done and to send me the results. She agreed, but she was distraught and asked me to come and take a look at her operation. I balked at first, but after a few minutes of begging I gave in. I asked Chad if he’d like to join me on a trip to the nursery the next day; he agreed and we were off.

The nursery that we found was a retail operation on a road which was once a major thoroughfare, but had been reduced to a minor highway when the interstate, which ran parallel, had been expanded. Still, it seemed like a pretty good location for a retail nursery in terms of customer traffic. After we parked the car Chad hopped out and began inspecting balled and burlapped evergreens while I joined the manager to look at their container stock. It was a mess. It was the end of summer when we visited, but the leaf drop made it look as though we were in the late fall.

I popped a potentilla out of a container and could find no roots reaching the containers edge. Taking a closer look I quickly discovered one major problem. These were bare root plants planted into containers filled with soil. Soil is almost never a good thing to put into a container because it’s usually too heavy and prevents air from working its way down to the plant’s roots. The gentleman who owned the nursery (not the manager – in most cases she just seemed to do what the owner wanted to do) was a farmer who had decided that it made sense to save money by using this soil which grew his field crops so well. This nursery was buying bare-root plants, popping them into containers filled with field soil, and then selling them at quite a mark-up (by the way, this is considered an unethical practice).

This field soil was obviously a problem, but, while plants usually suffer because of the use of soil in containers, I didn’t think it was likely to cause the carnage that I was seeing. I asked about their fertilizer and watering practices. Both of those seemed reasonable and unlikely to cause a major problem.

Meanwhile, Chad came back to report on the evergreens. Almost all of the evergreens (which showed signs of repeated shearing – good for Christmas trees — not good for the long term health of landscape trees) were missing needles close to the base of the tree and appeared to be suffering somewhat. I thought it might be a water issue, particularly if city water were being used, and asked where it came from. The manager told me that all of their water came from a well on site. In this part of the world we frequently have issues with well water being too alkaline, but it usually doesn’t cause the type of damage that I was seeing here. I filed water away as a possible, but unlikely cause.

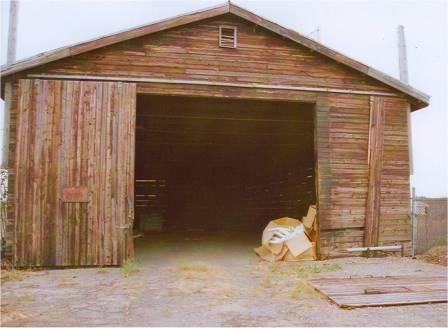

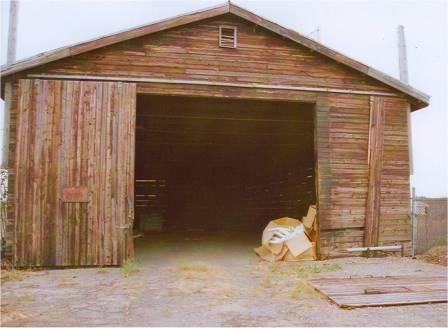

I was pretty stumped, as was Chad. Obviously we saw problems, but these just didn’t seem sufficient to cause what we were seeing. The manager offered to show us the potting operation, we followed. The first thing that struck me about the potting shed was that it seemed old, and yet the timbers themselves hardly showed any rot which is kind of unusual. We asked when the shed had been built and the manager indicated that she had reason to believe that the shed had been built in the 1940s or 50s.

We entered the shed and noticed a large pile of what we assumed to be soil. Nothing special. Then our eyes began to adjust to the dim light and we realized that this was no ordinary pile of soil. It was mostly white. We were confused. The first thought that went through my head was “what is this, cocaine?” Then I thought, no, it must be perlite. I looked at Chad. His eyes were big and round. I went over to the pile, poked my finger into it, and then touched it to my tongue.

“What the EXPLICATIVE DELETED is this place?” I asked Chad (OK, I may not have used those exact words, but it was something close). The manager must have overheard.

“Well, it’s a potting shed now, but it was built to store salt for the highway” she responded. “That’s just a pile of leftover salt. We stack our soil against it when it comes in.”

We tested both the soil from the pots and their irrigation water. Both were ridiculously high in salt (and, not coincidentally, sodium levels). In fact, salt levels were high enough in the irrigation water that it would literally burn foliage off of the plants.

Shortly after visiting this nursery Chad became a Buddhist and my beard turned more gray than brown. I can’t swear that it was this nursery that caused these changes, but I can tell you that I haven’t been the same since.