This time of year, I often get asked for a forecast for the coming growing season. Will we have a drought? Will it be warmer or colder than normal? Will we have any tropical storms in our area? All of these things affect how farm crops (and gardens) will perform over the next few months and how big the yield might be when it comes time to harvest. In this week’s blog, I will look at some of the factors that go into seasonal forecasting and how it all comes down to numbers.

How are seasonal forecasts made?

Seasonal forecasts use computer models to look for large-scale patterns in weather that affect what the climate is likely to be on monthly to seasonal time scales, but also use statistical methods based on observations from previous years to determine what the most likely climate conditions are. The predictions are usually based on several factors, including current conditions, long-term trends, and other regional variations like El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which we’ve discussed before.

Current conditions are important because they define the starting point of the prediction. If you are starting from a drought, for example, you would not expect that next month would be much wetter than normal because the dry conditions would make it hard for rain clouds to form unless you have an unusual event like a tropical storm or atmospheric river that comes along and changes conditions on the ground quickly. Long-term trends are important because they define the base state of how the climate is behaving. If you are on an upward trend towards warmer temperatures, as we are now with global warming, it is more likely that you will observe a month or season that is above normal than below normal. If there were no trend in temperature, then seasons that were colder or warmer than average would be equally likely. You can find climate trends for your local area using the Climate at a Glance tool and picking your own country, state or county.

Knowledge about regional variations like ENSO also contributes to seasonal forecasts because the atmospheric and oceanic climate conditions which help define those oscillations can last for months or sometimes even years, making long-term prediction easier. The pattern of the atmospheric waves associated with those oscillations defines where warm and cold air are located as well as the position of the jet streams that blow storm systems around. In some respects it is like putting a rock into a river—when you have warm water in the Eastern Pacific Ocean as we do now in advance of the coming El Niño, thunderstorms develop vertically over that warm water, and those towers of rising air divert the flow of air currents that push weather systems around just as a rock diverts the flow of water in a stream. If the warm water were not there, the atmosphere would likely have a very different pattern.

Oirase Mountain Stream – Towada, Aomori, Japan, Daderot, Commons Wikimedia

Forecasts based on ENSO work best when it is at one extreme or the other and in areas where the differences between El Niño and La Niña conditions are most pronounced. That makes ENSO more useful for making seasonal forecasts in the Southeast United States and in northern states where statistical relationships are well-defined than in the central U.S., where there is a weaker statistical relationship between the ENSO phase and the local climate. Climatologists look at similarities between different El Niño years using statistics to identify recurring patterns that can help to predict the climate the next time an El Niño occurs, although other factors can come into play that throw off the forecasts.

How do seasonal forecast maps depict the future climate?

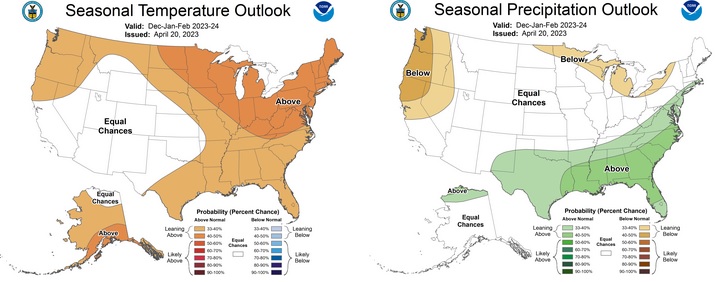

For the United States, seasonal forecasts are presented as maps with probabilities of above, near, or below normal temperature or precipitation. If there was no hint in any of the predictors of what would happen, each of the three categories would have equal weight, or a 33% chance of that climate category occurring. Those forecasts are based on current conditions, what they expect to happen in the months after the prediction made, the long-term trends that are pushing the temperatures or precipitation upward or downward, and the expected state of oscillations like ENSO. You can see the whole suite of 3-month forecasts for the next year for the United States at https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/90day/.

In the maps above, the outlook for December 2023 through February 2024 is shown. In the temperature map, the climate has a higher probability of being warmer than normal in the northern part of the country, especially the Northeast. This is consistent with the expected pattern of temperature in an El Niño winter. But the prediction of warmer than normal weather in the Southeast is not what we expect if we look only at El Niño. It also includes the effects of greenhouse warming, which is likely to overcome the cooler conditions that would be expected in the Southeast from El Niño alone. On the other hand, since there is not much long-term trend in precipitation, the precipitation outlook on the right shows a clear El Niño signal with wet conditions along the Gulf and South Atlantic coasts and dry conditions in the Northwest and to a lesser extent, in the Upper Great Lakes. In the Southeast, El Niño winters are expected to be cooler than normal because all the clouds associated with the rainy conditions keep daytime temperatures down.

What do we expect for this year?

Because the El Niño is coming on strong, I expect it to drive a lot of this year’s growing season climate. While it is still weak, it won’t have much impact on our regional climate variations, which makes summer difficult to predict. In that case, we look more towards the current conditions and trends to conclude that areas that are already experiencing drought are likely to get worse, and areas that are starting out wet may get a reprieve from drought conditions for a few months.

The biggest impact of an El Niño in the growing season is in how it affects developing Atlantic and Eastern Pacific hurricanes. In El Niño years, tropical systems in the Atlantic tend to be fewer in number and weaker because the strong jet stream aloft keeps tropical cyclone circulation from strengthening into tropical storms or hurricanes. In the Eastern Pacific, it is just the opposite, with more storms forming than usual. That can help feed moisture into the Southwest. Of course, it only takes one storm coming over your home and garden to cause tremendous damage, so you need to prepare for storms if you live in a hurricane-prone part of the United States or other Northern Hemisphere location.

By fall, the El Niño is expected to be well developed and areas where El Niño usually brings rain could see the wet conditions start earlier than usual. For farmers, that means harvest could be difficult if conditions are wetter than usual, and it might be hard to get that last cutting of hay. Winter could be drier than normal in the northern states since many of the rain-bearing storms will be farther south than usual, although you will certainly see some rain.

This article provides an insightful overview of the challenges and limitations of seasonal forecasting in the realm of horticulture and gardening. This emphasizes the importance of understanding the factors influencing weather patterns and the need for caution when interpreting long-range forecasts. It’s a valuable reminder that while seasonal forecasting can offer some guidance, it’s crucial to rely on local knowledge and adaptability when making gardening decisions.