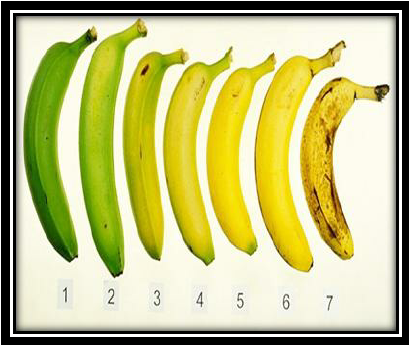

“Will my peppers continue to ripen? How about my eggplants?” It is common knowledge to most gardeners (and home cooks) that tomatoes will ripen on the kitchen counter, as will bananas and several other fruits. You know that one day your bananas look perfectly ripe and the next they’re a brown mush But does this work for all fruits? We often get questions about whether specific fruits will continue to ripen after picking. And the answer is….. it depends.

One of these fruits is not like the other

The answer as to whether a fruit will continue to ripen after harvest depends on which one of two groups it falls into. These groups are climacteric and non-climacteric fruits. In short, climacteric fruits are the ones that will continue ripening after harvest and non-climacteric fruits are ones that don’t ripen after harvest.

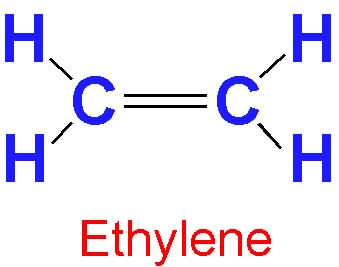

This refers to the “climacteric phase” of fruit ripening where there is an increase in the gaseous plant hormone ethylene and an increase in respiration, which drives the ripening process. It is the climacteric fruits that will keep ripening once they’ve been harvested, thanks to ethylene. The only stage of maturity for non-climacteric fruits after harvest is…..compost.

As long as you’re green, you’re growing. As soon as you’re ripe, you start to rot. -Ray Kroc

Almost all fruits produce ethylene, but non-climacteric fruits produce them at much lower levels and do not rely upon it as the main driver of ripening. I’ll go into a bit more detail in a bit, but first – which fruits are climacteric and which are non-climacteric?

| Common Climacteric Fruits | Common Non-Climacteric Fruits |

| Apple | Brambles (raspberry, blackberry, etc). |

| Apricot | Citrus (oranges, lemons, limes, etc.) |

| Avocado | Eggplant |

| Banana | Grape |

| Blueberry | Melon (including Watermelon) |

| Cantaloupe / Muskmelon | Pepper * |

| Cherry | Pumpkin |

| Fig | Squash (summer and winter) |

| Kiwi | Strawberry |

| Mango | Cherry |

| Papaya | |

| Pawpaw | |

| Peach | |

| Pear | |

| Plantain | |

| Plum | |

| Tomato | |

| *Some evidence of climacteric ripening in hot peppers | |

The ripening process

Ripening is genetically programmed – meaning that it is highly dependent on processes that are regulated by genes and it specific to each species. Parts of the process are started and stopped due to the transcription and translation of genes, which are in turn controlled by signals such as chemical compounds, physiological stages of the plant, climate, and so on. These ripening processes have a lot of end results – sugars accumulate in the fruit, pigments develop, some compounds that have pleasant flavors develop while others that are unpleasant are broken down, some of the pectins in the fruit break down to make it softer, and on and on.

Research shows that ethylene, the simple little gaseous hormone plays a crucial role in the ripening of climacteric fruits by altering the transcription and translation of genes responsible for ripening. Ethylene is the dominant trigger for ripening in these plants. Ethylene receptors in the cells are triggered by the presence of the gas which leads to cascade effect. This is why ethylene can be introduced from other fruits to trigger ripening in fruits that aren’t ready to ripen. If you’ve heard of the tip to put an apple in a bag full of some other fruit to get it to ripen, it actually works – as long as it is a climacteric fruit.

The same ripening processes happen in non-climacteric fruit as well, but they are not dependent on the presence of ethylene. In fact, these pathways are also present in climacteric fruits – the ethylene-dependent processes are just the dominant (and faster) way that they ripen.

Controlling ripening

The dependence on ethylene for a vast majority of fruits to ripen has been used by farmers and the food industry for a long time to keep climacteric fruit more stable for shipping. These fruits are harvested “green” before they ripen and shipped unripe since they are much firmer and much less likely to get damaged in transit. These days, bananas, tomatoes, and other climacteric fruits are likely to be given a treatment that temporarily inhibits the ethylene response before harvest or shipping to extend their shelf life further. Once they’re close to their final destinations they’ll either be allowed to ripen on their own or given a treatment of ethylene to speed back up the ripening process.

What we gain in shelf-life and reduced food waste we do lose in a bit of flavor. Since the fruits are no longer attached to the plant when they ripen they don’t have the chance to transport more sugars and flavor compounds from the mother plant. So “vine ripened” fruits do have a bit more sweetness and flavor than those that are picked green. Having just gotten back from Rwanda, a country where bananas are a common staple food I can attest that the ones that ripen on the plant are much sweeter than those we get shipped in to the US – you know, the ones that will ripen next week sometime if you’re lucky. There were even some in our group that don’t care for bananas here that loved the ones we had at breakfast every morning.

One possible direction for biotechnology is the engineering of plants to alter or eliminate the ethylene ripening response to reduce food waste and spoilage. Since many genes that are responsible for ethylene production such as enzymes that catalyze the production of ethylene precursors, or proteins that serve as ethylene receptors have been identified, work is being done to develop delayed ripening by altering or knocking out these genes in a variety of crops.

Sources

Alexander, L., & Grierson, D. (2002). Ethylene biosynthesis and action in tomato: a model for climacteric fruit ripening. Journal of experimental botany, 53(377), 2039-2055.

Pech, J. C., Bouzayen, M., & Latché, A. (2008). Climacteric fruit ripening: ethylene-dependent and independent regulation of ripening pathways in melon fruit. Plant Science, 175(1-2), 114-120.

Lelièvre, J. M., Latchè, A., Jones, B., Bouzayen, M., & Pech, J. C. (1997). Ethylene and fruit ripening. Physiologia plantarum, 101(4), 727-739.

Why do my pumpkins turn orange off the vine? I just read somewhere that I should do that to avoid rotting in field, therefor not being marketable.

this year was the first time I noticed unripe mild peppers, Carmen, Escamillo and Lunchbox, turn color in my refrigerator

I have sweet peppers, including Escamillo, piled on trays and in baskets here in the kitchen, all picked green and morphing to their fully red or yellow, and delicious, stage.

There is some limited evidence that some peppers will undergo a post-harvest ripening process. Most sources point out that it is a non-climacteric ripening process, unlike the process in tomatoes and other climacteric fruits that ripen in response to ethylene gas. (https://www.mpg.de/5934313/peppers_ethylene_maturity). As a chart in the article points out, there is some evidence that a few of the chili peppers do ripen climacterically (Escamillo probably does, as I’ve seen other comments about its ripening.) There is also some evidence that a few peppers ripen through a non-climacteric route (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19756789/). But most peppers do not continue to ripen (this is how you have both green and red/yellow/orange bell peppers available at the grocery store – if they continued to ripen it would be hard to have green bell peppers). Enjoy your escamillos! I may have to grow some in the future – it would be handy for the end of the season when you have to pick everything before the big freeze!

All the information that I have found regarding sweet cherries states that they are non-climacteric. eg: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4473978/. Have they been re-classified?

Good catch. I think it was a formatting issue with the table (it was out of alphabetical order with the other fruits). I’ve fixed it in the table. Thanks!

Fruit doesn’t ripen after picking, that is a pernicious marketing lie peddled by the world’s supermarket pr and marketing machine. Ripening fruit on the plant continues to receive sap during real ripening proces, it not purely starch to simple sugars but a highly orchestrated physiological process during which much more happens, eg dehiscence of stem, increase in aromas etc . Picked unripe fruit doesn’t. Picked unripe fruit undergoes a process of decomposition which in climacteric fruit resembles ripening. It gets a little sweeter in an adaptation to get eaten. Sometimes is succeeds. Other times it rots without much improvement in quality. Usually it’s between those extremes and it’s purely a matter is taste, sugar levels and mostly marketing budget where in that point you seem a fruit to be ripe.

Even “real” ripening (i.e., fruit left on the plant) is a process of decay; the fruit exists as a means of seed dispersal and its stages of ripening and decay appeal to different types of fruit consumers. In climacteric fruits, ripening is associated with bursts of ethylene gas production which hastens ripening and decomposition. Nonclimacteric fruit harvest by fruit consumers relies on other cues (visual, olfactory, textural). The trick to harvesting fruit, climacteric or otherwise, is catching it at the proper stage of decay.