While most of the country is in the middle of a heat wave and the mercury is creeping past 100F on many thermometers, lets do a little exercise to help you feel cool as a cucumber (though not straight out of the garden, those cucumbers would likely be hot). I want you to think about a crisp September morning. You’re out walking through your vegetable garden and you stop to appreciate a big, emerald green head of broccoli. Just a few feet away, stalks of Brussels sprouts, those miniscule cabbages that have somehow overcome years of revulsion to become sexy and desirable (they must have a good agent) shoot up like skyscrapers around the rest of the plants. Lush lettuce fills in a bed nearby, and some cucumbers and beans that you planted late are looking as fresh as a newborn chick.

Sounds beautiful, doesn’t it? Well I’m here to tell you that you can actually make this a reality. You can have a super productive garden this fall, and for most areas of the country the time to start planning and planting is now. Right now, when a cool refreshing fall morning seems as far away as a trip to the moon. Of course, the exact timelines and planting schedules differ by region due to the length of growing season, but most places in the US (and the northern hemisphere) can start thinking now about planting crops for the fall. For exact timing in your area, you may want to connect with your local extension system for gardening guides.

While many experienced gardeners may know this and practice fall garden planting, there’s a lot of people out there who have yet to have the pleasure. And given the huge number of first time (or first time in a long time) gardeners, these garden basics might be helpful to get the most out of those pandemic plantings.

In fact, fall is one of the best times of the year to garden. Aside from cooler temperatures making it more pleasant to garden, there’s often less pressure from diseases and insects to ruin crops. In addition, many of those cool season crops, like the ones I mentioned above, actually are more productive in the fall than if planted in the spring. Even though they get a hot start in mid- to late- summer, the cooling temperatures of fall around the time many of the crops come into maturity extends the harvest period and improves overall quality of the produce. You also have the benefit of removing some of those spent and diseased warm season plants and swapping them out for something fresh and new– a garden revival of sorts.

Unfortunately, since fall vegetable gardening isn’t as widespread as planting summer gardens, plants and seeds can often be hard to find when it is actually time to plant (so planning ahead is helpful). Mid-summer is usually the time for most regions to start seeds for those slower growing cool season crops like broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, and their kin. They can be started indoors, but the need to do so isn’t as great as it is for those warm season crops we start indoors in late winter. You can start them in pots/flats outdoors as long as you have somewhere that isn’t so hot and sunny that they’ll be continually drying out (some shade would help). They should be ready to transplant by late summer. You can skip the seed starting/transplanting if you want to try direct seeding into the garden, but as they say “your mileage may vary”.

Some of the fast maturing warm season (frost tender) crops are also good candidates for a mid-summer planting as a way to refresh the garden if you have space for it. Beans are a good candidate for late-summer planting, but you’ll need to make sure they are a fast-maturing variety (there’s a wide range of maturity times in beans). Bush beans are usually the quicker growers. Pole beans and lima beans usually take a longer period, so those don’t do as well later in the season for places that have frost and freezes.

It is also a possibility to squeeze in a late crop of cucumbers or summer squash as well. This can be good if your cukes and squash succumb to disease, squash vine borers or cucumber beetles. Planting late can often mean that you are missing the primetime for specific pests. For example, squash vine borer adults actively lay eggs in the early season but largely disappear later on. A late planting means you could miss them entirely.

Fall is the best time to grow leafy green vegetables. Lettuce, which does not fare well in the summer, thrives in the cooling temperatures of the fall. Other leafy greens, such as chard, spinach, and kale are also winners in the fall garden. Many of the root vegetables, such as turnips, carrots, beets, and radishes are also part of the fall garden revival. You’ll want to wait until temperatures have chilled a little to get these started, but not so late that the season ends before you get good growth.

You gotta know when to sow ‘em

The key to fall planting is to know how many days it takes for the crop to mature. Check out the seed package or the plant tag — there should be a time to maturity on there. Just count backward from the first frost date. Be sure to add a few weeks to account for slower growing in cool weather and to allow for a reasonable harvest time.

For example, if I wanted to plant a late crop of beans, I might select the cultivar ‘Contender’ which matures in about 55 days. I want to add at least a few weeks onto that for maturity and harvest time, so lets say I need 75 days (I can go shorter if I want to accept the risk of an early frost). Let’s also say that my first frost date in the fall is October 20. Counting back 75 days from October 20, I get August 6 – I should plant my beans no later than that date to get a harvest.

Most of the cool season crops can tolerate a frost (and some even a freeze) so their growth dates can extend beyond the first frost date. You’ll just want to have them mostly grown and close to maturity before it gets cold enough to stop their growth. I covered frost and freezes and which crops can survive those cold temps in this previous GP article.

You can give yourself a little more time if you plan on incorporating a season extension practice in the garden. Using a row cover or constructing a low tunnel can give you several more weeks of growing time. It can be possible to enjoy a fresh tomato or green beans straight from the garden on the Thanksgiving table, or some fresh broccoli or kale at Christmas even in some of our colder regions. But it all starts with a little planning in the heat of summer.

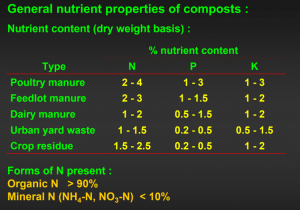

And if you choose not to plant a fall crop, I would suggest using a cover crop in garden beds as you remove this year’s plants. A cover crop will help keep weeds to a minimum and preserve soil structure and nutrients through the winter. Winter wheat, rye, and crimson clover are good winter cover crops. Next spring you just cut them down and till them in if you’re not practicing no-till (and you should be if at all possible). For annual cover crops, you can usually cut them down or break them over and leave them in place as a mulch. You can also pull them up and compost them to add directly back to the garden, especially if (since it is hard to till or mow in a raised bed). This GP article is an oldie but goodie for using cover crops in the vegetable garden.