There’s a scandal simmering all across the United States that brings to mind a switched at birth storyline on a steamy soap opera or telenovela. This scandal, though, isn’t about babies, its about….peppers! Jalapeño peppers, to be exact.

The issue, dubbed #Jalapeñogate online, has many home gardeners scratching their heads as to the identity or the issue with the peppers that they planted. You see, instead of those glossy dark green peppers that many are used to putting in their salsas and other favorite spicy dishes, the plants are producing bright yellow peppers. Some of them are the same shape as jalapeños and some look more like banana peppers.

The phenomenon has gardeners, farmers, and officials in multiple states scratching their heads. It turns out there are no stolen tapes with evidence of the problem. Instead, I was first alerted to the problem when some of the garden Facebook groups in Nebraska were abuzz with posts about the mystery peppers. I’ve since seen news I’ve seen the issue mentioned in news articles from Oklahoma, Kansas, and California and have seen posts on social media sites such as Reddit and TikTok. I scoured many of these sources (TikTok was surprisingly the most informative) and confirmed it with info from friends in the seed industry.

So what happened? It turns out that the seed trade is global and multi-tiered and sometimes mix ups occur. It just so happened that this year there were a lot of them. One US seed company that supplies a lot of seeds to nurseries and other seed companies, called Seeds by Design, imported some of its seeds for the current season. The company supplies many interesting and niche seeds, many of which it develops or breeds (they are responsible for the award winning Chef’s Choice tomato series and several other vegetable cultivars that you’d recognize on the seed rack). But it also purchases or imports seeds often for more common varieties. Seeds by Design supplies seeds to many nurseries, growers, and even seed companies around the country. And that’s where the trouble starts.

The company imported seeds from an international grower that turned out to be mislabeled. Up to five different cultivars were accidentally swapped and resulted in pepper pandemonium across the country. It turns out that more than jalapeños were affected, so we should really change it to just #Peppergate. Here’s what was switched:

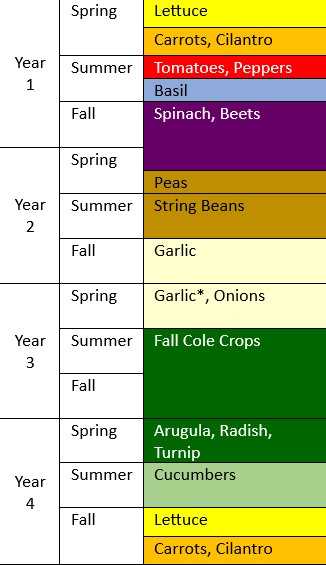

| What was supposed to be… | Turned out to be… |

| Jalapeño (green cultivar) | Jalapeño ‘Caloro’ (yellow cultivar) |

| Jalapeño ‘Tam’ (mild green) | Sweet banana pepper |

| Hungarian Sweet Wax | Bell Pepper ‘Diamond’ |

| Bell Pepper ‘Chocolate Beauty’ | Sweet Pepper ‘Red Cherry’ |

| Bell Pepper ‘Purple Beauty’ | Hungarian Hot Wax |

Gardeners could have bought these at local garden centers or nurseries as transplants. I know of at least two local/regional garden centers that sold the affected plants. I’ve also seen that gardeners who bought seeds from some suppliers (I’ve only seen Ferry-Morse so far) may have received at least switched bell peppers.

What does this say about our seed and food supply?

Our food system and our seed system are global. We live in a global economy and companies buy and trade with each other all the time. Given the scale of this trade, mistakes can and do happen. I’ve seen some people try to drag Seeds by Design because they purchased seeds from a foreign company that just happens to be in China. But the company doesn’t deserve that. They had no knowledge of the mix up until the peppers were in the hands of growers and peppers didn’t look right. Can you tell the difference between pepper cultivars by seed?

And others have tried to make an issue about trading with China with some comments that hint at outright racism. While there are some security concerns about trading with countries like China, especially in the tech world, trading simple commodities like Jalapeño seeds is standard practice. I’ve also seen comments that importing ag products from other countries means that we can’t support ourselves. But it turns out that we sell a whole lot more agricultural goods to China than we buy. US producers sold a record-breaking $200 billion (with a b) worth of agricultural products to China in 2022 while we imported $9.5 billion from them.

Given the need to feed so many people economically, we often import from countries that have better capacity to grow what we need due to climate, land, and labor differences. We also have to take into account seasonal differences. Even US based seed production companies and breeders will grow in other countries to take advantage of multiple growing seasons. Given our reliance on horticultural imports, we have a robust inspection system to make sure the foods, plants, and seeds we receive from countries like China are indeed safe.

To wrap this mystery up –

While there’s not much you can do now that you have these mystery seeds, enjoy the fun of trying something unexpected. If you ended up with a pepper that you don’t like or can’t eat (like the Hot Wax for Purple Bell switch), share with friends or donate to a local food pantry. After all, you can’t tell that the jalapeño isn’t green when it’s turned into a jalapeño popper.

Sources

https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/record-us-fy-2022-agricultural-exports-china