You might have heard of the concept of crop rotation, or even have had someone tell you that you should be practicing it in your home garden. But does this practice developed for use on large-scale farm fields work for small-scale home gardening or backyard farming? And if so how do you even do it? Let’s take a quick look at the practice and learn how you might implement it in your own garden, no matter the size, if it is practical to do so.

The Benefits of Crop Rotation

The benefits of crop rotation touted to home gardens for annual fruit and vegetable plants focus mainly on Integrated Pest Management. Keeping certain crops in one spot in the garden year after year can lead to a build up of plant disease microorganisms and insect pests in that area. These findings are largely based on large-scale production systems, like where whole fields that are hundreds of acres are grown as the same crop and switched from year to year. But there still is some benefit for the small-scale gardener, especially with disease build up from soil-borne diseases or debris left in the garden.

The benefits are less clear for insect pests. Sure, there might be fewer insects that move from spot-to-spot or bed-to-bed in your home garden, but we must remember that insects can fly and a journey of a few feet from one raised bed to the next might not be much of a barrier. It is sort of like when people ask us if using grub control in the lawn will control Japanese Beetles in their garden. There will likely be a small reduction in the population, but we remind folks that Japanese Beetles can fly pretty good distances, so control will be minimal.

Benefits of crop rotation lay below the soil. Different plants use different ratios of nutrients and some even add nutrients to the soil. Legumes have nitrifying rhizobia bacteria that colonize their roots in a symbiotic relationship and there is a net nitrogen increase in the soil after legumes such as beans, peas, alfalfa, or clover have been grown. That’s why one of the major crops added to crop rotations in the “corn belt” is soybeans (or just “beans” if you’re from around these parts). The soybeans contribute nitrogen to the soil, which helps in the production system because corn is a heavy nitrogen feeder. This is especially true if the roots are left behind or if the legume is incorporated like a cover crop.

Given that crops uptake nutrients in different ratios and that some input nutrients into the soil, by planting the same crop year-after-year in the same spot you can end up with nutrient imbalances, especially in raised beds or small plot areas. Using cover crops and incorporating them into the soil is another facet of crop rotation that can build soil organic matter and address nutrient issues. Fertility can also be adjusted with fertilizer and compost, but using rotation will help with overall management.

Rotating in root crops like carrots, radishes, and turnips can also allow for some good soil aeration, especially in no or low till garden situations.

There’s also research that shows that different plants exude different compounds, like sugars, etc. that attract and feed different microorganisms and rotations which help increase the diversity of the microbiome in the soil. This will not only improve the soil ecology in your garden, but a healthy microbiome can compete with some disease-causing microorganisms to reduce the likelihood of soil-borne disease. Most of us have been told that eating cultured yogurt increases good microbes in the gut and can reduce the likelihood of some illnesses- its kind of like that, but for plants.

How to rotate crops (especially in small gardens)

While crop rotation might not solve all the world’s problems or your garden insect issues, there are still definite benefits to the practice if you can manage it. For some people garden space is too limited. How do you rotate crops when all you grow is a few tomatoes in the corner of a flower bed? Other than putting them somewhere else every year, there isn’t much you can do.

If you have a large garden and especially if you have one that’s a larger tilled-up spot (don’t get me started on tillage), you should definitely be implementing rotation. While I typically garden in raised beds, that usually makes it easy. Crop rotation usually occurs by plant family, so plant families rotate to a new bed each year (more on plant families in a bit).

In general, a crop rotation plan should mean that plants from the same family aren’t grown in the same place in the garden for at least four years if possible. If I plant tomatoes in “Bed A” in my garden this year, then I shouldn’t plant them in “Bed A” again for at least four years if possible. If you’re not growing in beds, then should rotate by rows or by areas of the garden.

Is this practical for every gardener? No. So I say do what you can. If you have a small space and only grow a few things and want to rotate crops, you can do so by time rotation – growing different crops each year. Or adding some container gardening to the mix and rotating crops into containers in different years. As a side note, using containers can be an effective way to rotate crops because you don’t necessarily need to rotate the plants if you can rotate (replace) the soil from year to year (or at least replace the top layers).

Crop rotation can also aid in succession planting. For example, I don’t follow my beans with corn, I follow them with garlic, which is also a heavy nitrogen feeder and works right into the garden schedule to be planted in October after the beans are done. I’ll often do lettuce or leafy greens in a bed in early spring, then thin them out to plant in tomatoes or peppers when the time comes. Incorporating intercropping where you plant different sized plants around each other, like my lettuce and tomatoes, can also be an effective addition to crop rotation.

For a good crop rotation, you’ll want to plan. This would involve sketching/mapping out your garden or at least labeling different beds or spaces. Then creating a chart for each space where you list what crops will be grown there for the next several years will help you plan out to make sure you are giving ample time for the rotation process.

Keeping it in the family

Family members share lots of things and plant families are no different. Not only do some crops look similar but they can often share the same diseases. Keeping families in mind planning crop rotations is one of the easiest methods to keep track of which crops to include in a rotation. For small gardens it might make sense to keep members of the family together. For example if I only have four beds, I would want all the family members together so that I can have a true four year rotation. In larger gardens, realizing that crops are in the same family will help plan out for rotation of multiple crops.

Also keep in mind that some crops will overwinter (depending on where you are) so a fall crop might also be a spring crop in the same bed the following year. Some crops are also biennial depending on your local climate. For example unless you live in an area with winters cold enough to kill them, swiss chard, onions, and other crops will survive the winter and grow the following spring. I typically leave most perennial vegetables like asparagus and rhubarb, as well as perennial herbs like oregano and chives, out of rotations and put them in their own specific place in the garden (or elsewhere) since they don’t need to be replanted every year.

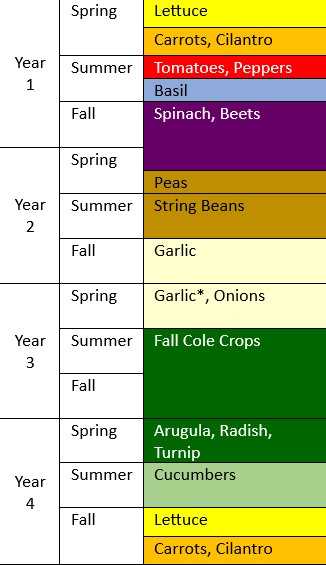

I’ve put together a list of common annual crops by family, as well as an example crop rotation plan for single garden bed/area. As an example, if I had four raised beds I would use this plan for each bed, starting in a different year for each bed so that I grow all the same crops each year, just in different beds.

In conclusion…

Crop rotation isn’t an end-all, be-all garden practice. If you can institute some sort of rotation in your garden you’ll likely see long-term rewards. However, if it isn’t possible or seems like too much work just remember don’t plant things in the same place year after year if you can help it. Any rotation, even if it is hit or miss, will be beneficial.

Sources

Benincasa, P., Tosti, G., Guiducci, M., Farneselli, M., & Tei, F. (2017). Crop rotation as a system approach for soil fertility management in vegetables. Advances in research on fertilization management of vegetable crops, 115-148.

Sasse, J., Martinoia, E., & Northen, T. (2018). Feed your friends: do plant exudates shape the root microbiome?. Trends in plant science, 23(1), 25-41.

Wright, P. J., Falloon, R. E., & Hedderley, D. (2017). A long-term vegetable crop rotation study to determine effects on soil microbial communities and soilborne diseases of potato and onion. New Zealand Journal of Crop and Horticultural Science, 45(1), 29-54.

Yasalonis, A. (2019) A must do in gardening: Vegetable crop rotation (UF/IFAS Extension). UF/IFAS Extension (blog)