As someone who has had a foot in Horticulture and a foot in Forestry throughout most of my career, people often ask me to compare the two disciplines. One of the truisms that applies in both cases is, “When all else fails, blame the nursery.” I’ve seen this following seedling die-offs in industrial forest plantations and I’ve seen it many, many times after street tree or landscape planting failures. In fact, if you believe some people, tree nurseries are responsible for every plague and pestilence to ever afflict mankind. Are some tree failures related to things that happened in the nursery? Of course. But there are lots of things that can go wrong between a nursery and a tree’s final destination; and even more things that can go wrong after it’s planted.

I know a lot of people don’t believe this, but nursery growers want their trees to survive and grow well after they leave their care. Growing trees is like making cars and any other business. You need satisfied customers if you expect to have repeat business. The best growers are always looking at their production practices for ways to improve their product. Last week I visited Korson’s tree farm in central Michigan. Korson’s grows Christmas trees and B & B landscape conifers. Rex Korson, the owner, has been concerned over the impact of root loss during transplanting of landscape trees. So much so, in fact, that he is conducting his own trial on root pruning.

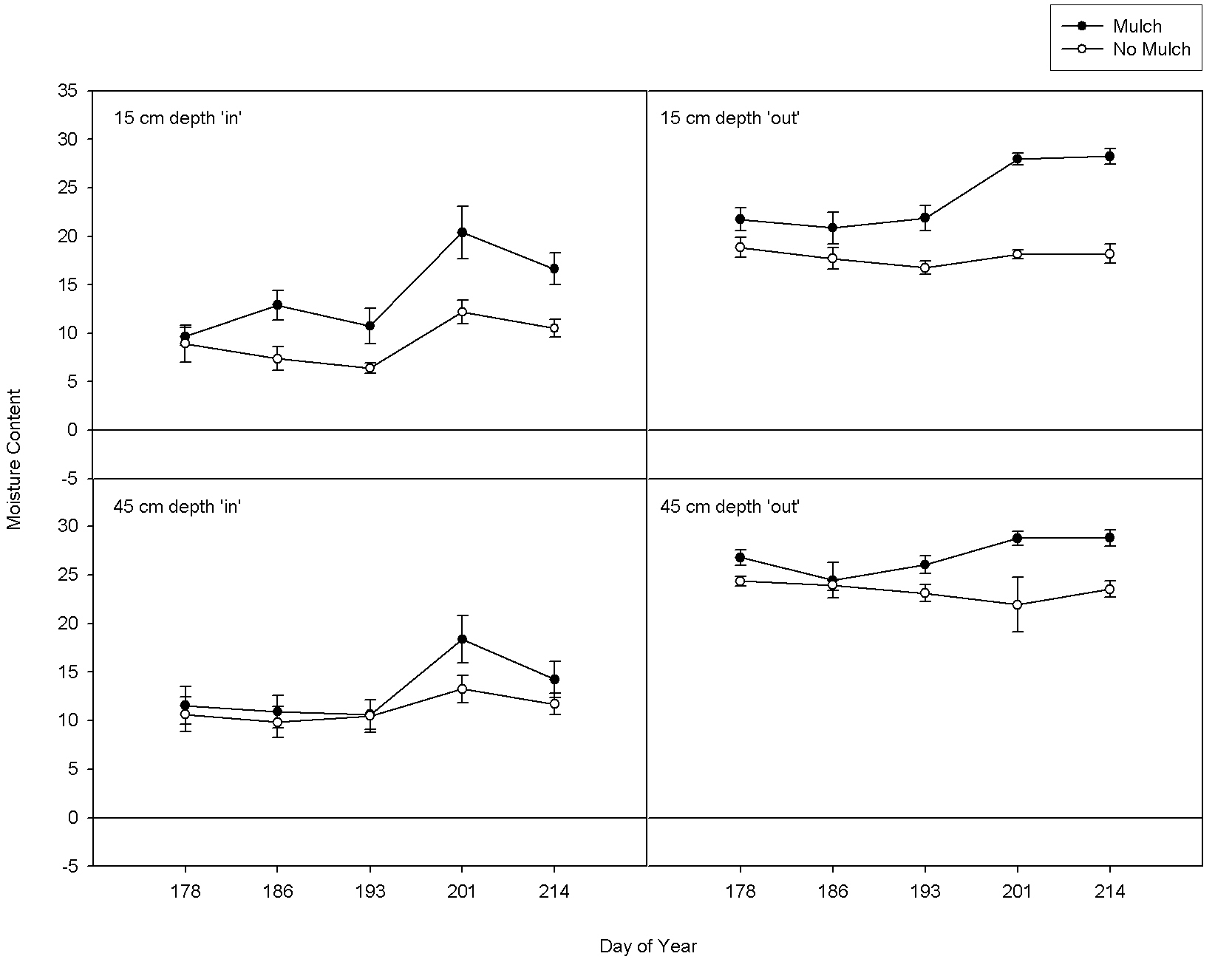

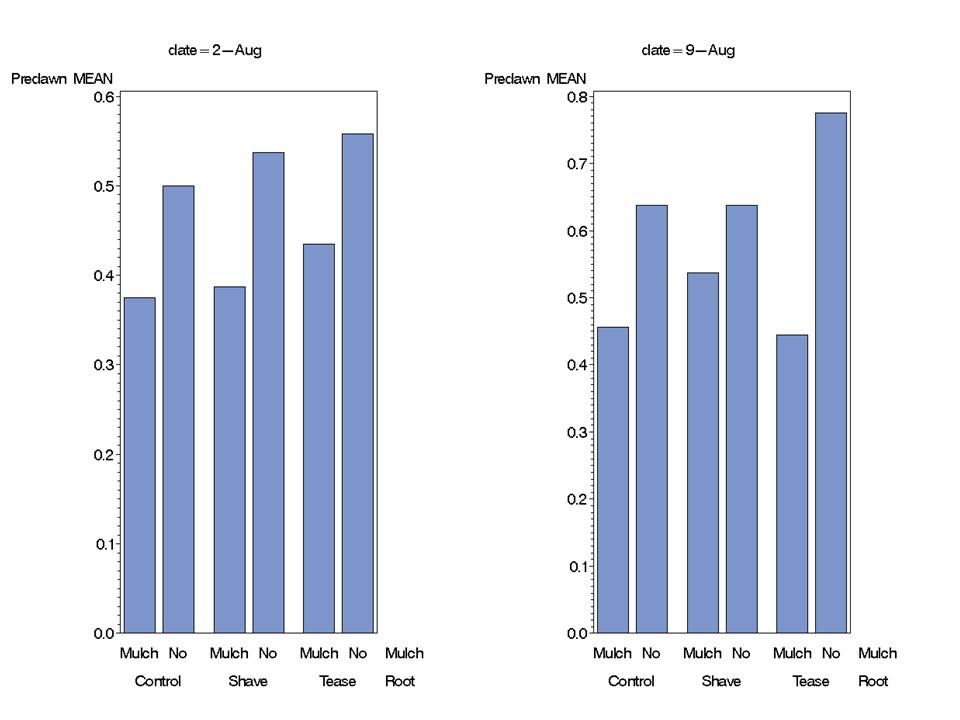

For those that are not familiar, root pruning of B & B trees is usually done a couple years before harvest by using a tree spade to severe tree roots. The spade used for pruning is slightly smaller than the one used for harvest, so that new roots stimulated by pruning are harvested with the root ball. Does it work? I did a root pruning trial a few years back to see if it could improve survival of fall-planted oaks and had mixed results. For Rex’s trees, however, the initial results were pretty impressive. In the first photo below are root systems of Norway spruce trees dug with a 30” tree spade. The second photo shows the root systems of trees dug with the 30” spade that had been root-pruned last October with a 24” tree spade. The response in one-year’s time was dramatic. At this point there no out-planting data but, other factors being equal, increasing the amount of roots harvested with the tree should increase transplant success.

I should hasten to point out that Rex is not alone. I work with many other growers in the state that are constantly tinkering with this or that in their production systems; sometimes on their own, sometimes with university specialists or extension educators. I’m not so Pollyanna to think that everything is always rosy in the nursery world but most growers, especially the better ones, are aware of the issues out there and are working to build a better tree.

Spruce dug with 30″ spade without root pruning

Norway spruce root-pruned in Oct 2011 with a 24″ spade and dug Oct 2012 with a 30″ spade.

Close up of new fine roots

Tree spade mounted on excavator for root pruning. With this system an operator can root prune 8 trees in 5 minutes.

</d