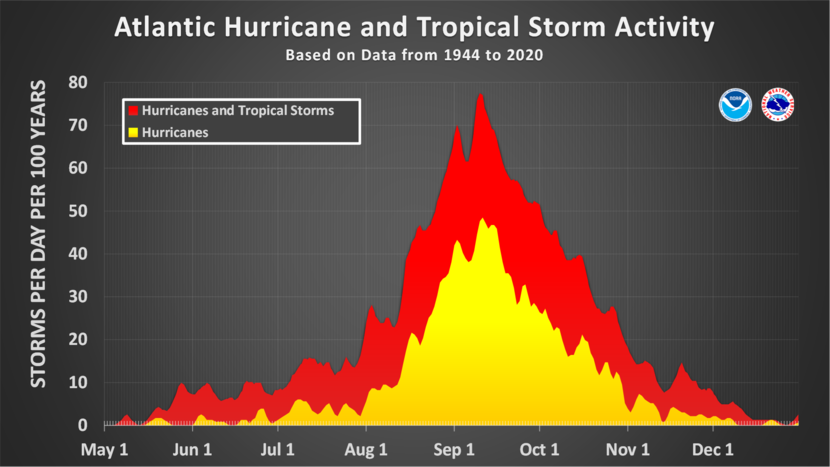

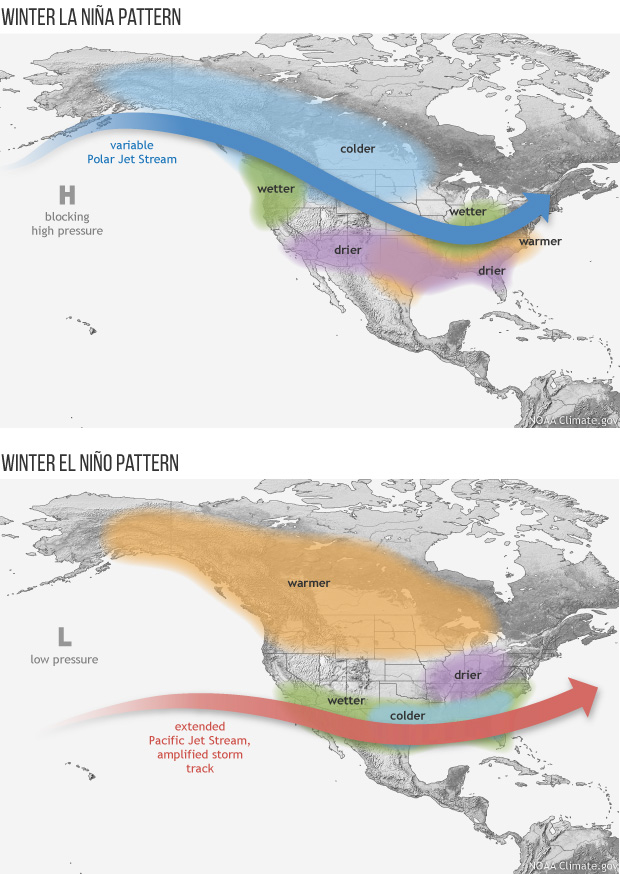

In my last blog post in early August, I noted how quiet the Atlantic tropical season has been so far this year. In fact, the period from early July through this week has been one of the quietest on record, with no named storms since the short-lived Tropical Storm Colin formed along the South Carolina coast and dissipated less than 24 hours later on July 3 in eastern North Carolina. The last time we had so few named storms was 40 years ago, so while it is not unprecedented, it is certainly unusual. And we are definitely later than the average date for the first hurricane of the year. By comparison, in 1992, a strong El Niño year, Hurricane Andrew (an “A” storm, so the first of the year) had formed and taken its devastating track through southern Florida and Louisiana by this date.

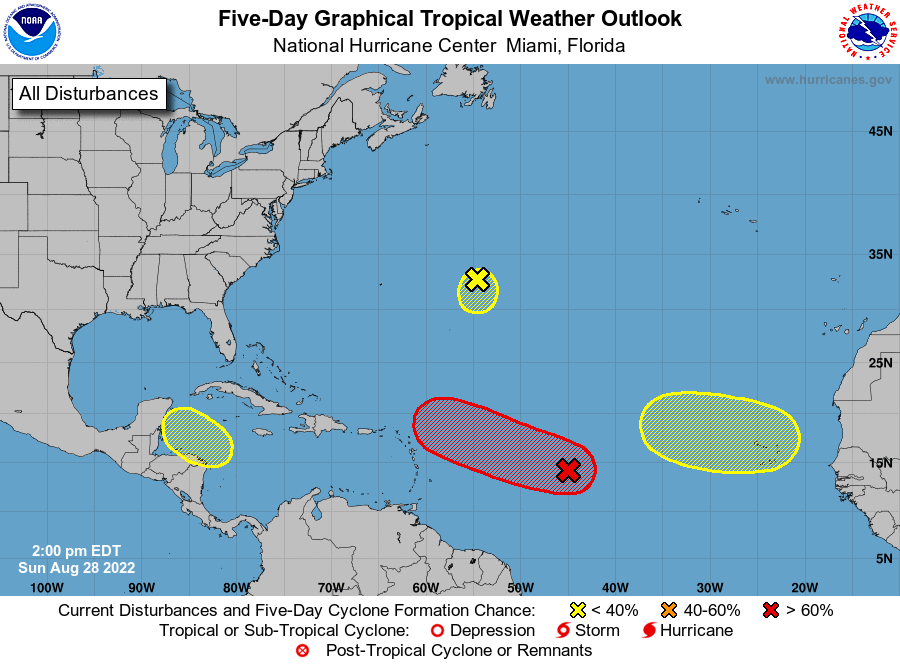

All of that is about to change, and hurricane forecasters are relieved after predicting a season of above-normal activity based on warm ocean temperatures and the current strong La Niña. They could still be correct. The National Hurricane Center’s 5-day map (as of 8-28-2022) is now showing four areas of potential development, with one area that has a 50% chance of development into a tropical depression within the next 5 days. Just in time for the peak of the season, according to the timeline we discussed earlier this month.

Why have the tropics been so quiet?

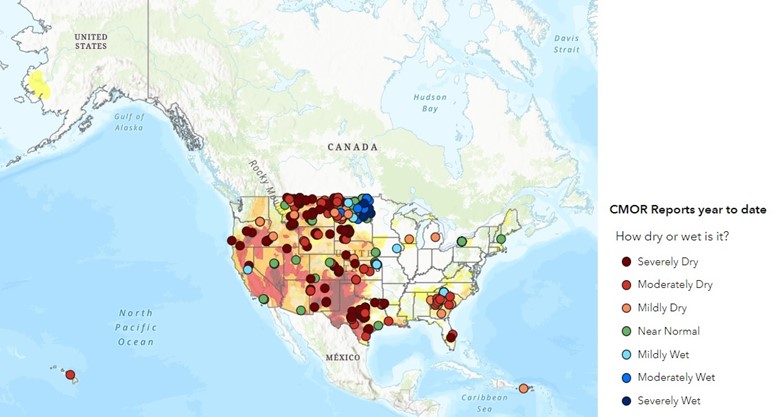

What caused the very quiet period in July and August? Hurricane climatologists point to several factors: the continuing clouds of dust that have blown off Africa and across the Atlantic Ocean towards the west, dry air moving in from Europe, which is experiencing its worst drought in 500 years, and the lack of strong waves moving off of Africa to act as seeds for tropical storm development. But the presence of warm sea surface temperatures and the lack of a strong jet stream (which is consistent with the presence of the La Niña) were expected to contribute to a stronger season than we have seen so far. If we can’t understand why this season has been so quiet so far, it means we still have a lot to learn about hurricane climatology and behavior.

The second half of the 2022 season is likely to be a lot more active than the first half, although forecasters have dropped the predicted number of storms from the early forecast due to the past two quiet months. If you live in an area affected by Atlantic hurricanes, you should be prepared for a more active pattern—don’t let the last two months fool you! If you live in another part of the world that is affected by tropical storms, you should also understand their climatology and likely impacts on where you are as well.

Some resources for following hurricane weather

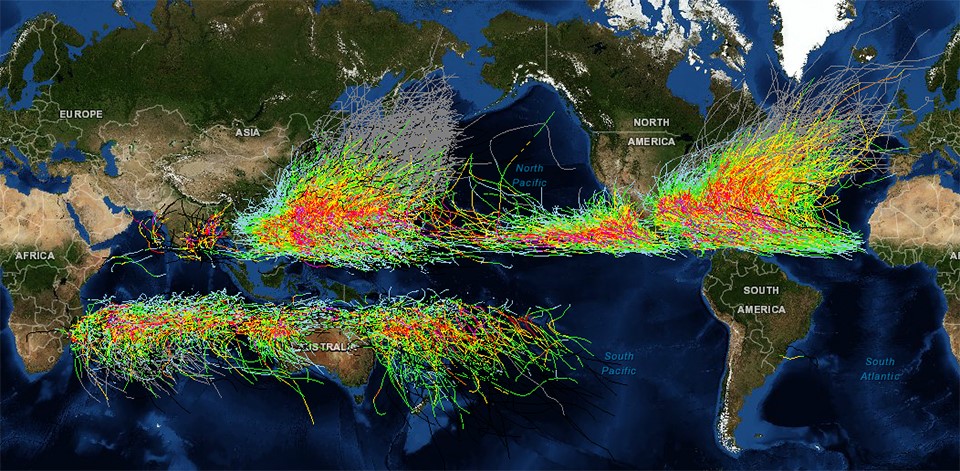

For those of you who are fascinated by tropical storms and hurricanes, even if you don’t live in an area that is prone to them, there are a few resources that you can use to track potential storms and follow them as they develop and move through areas that could be severely impacted by them. The first site I use is the National Hurricane Center, the source of official forecasts and outlooks for the season as well as specific storms as they form. Their website has a lot of information about past storms as well as educational resources on tropical systems. You can also find a lot of maps and climatological information at Mike’s Weather Page if you just need a quick look at maps and other images related to tropical weather in the Atlantic and Pacific Basins.

On social media, I follow Bryan Norcross and Brian McNoldy on Facebook and Twitter; they may be on other social media as well. Bryan Norcross is the television meteorologist who was working in Miami at the time of Hurricane Andrew; it has been fascinating this week to follow his timeline of Andrew from tiny disturbance to monster storm as it hit Miami and then Louisiana over the past week back in 1992, thirty years ago. Brian McNoldy is a senior hurricane researcher who works at the University of Miami and has done some interesting climatological work on past hurricanes as well as provides insight on the current season. There are also plenty of great local resources for local impacts if you live in a hurricane-prone area.

How to visualize the wind

If you are interested in looking at the wind patterns associated with storms, both tropical and extra-tropical, then there are three sources of fascinating maps that allow you to visualize the flow of air across the United States or the world:

United States current surface winds Hint.fm/wind. This site has a current map of the surface winds across the continental United States showing the wind speed and direction in motion. It is based on a near-real-time computer simulation to provide seamless coverage across the country.

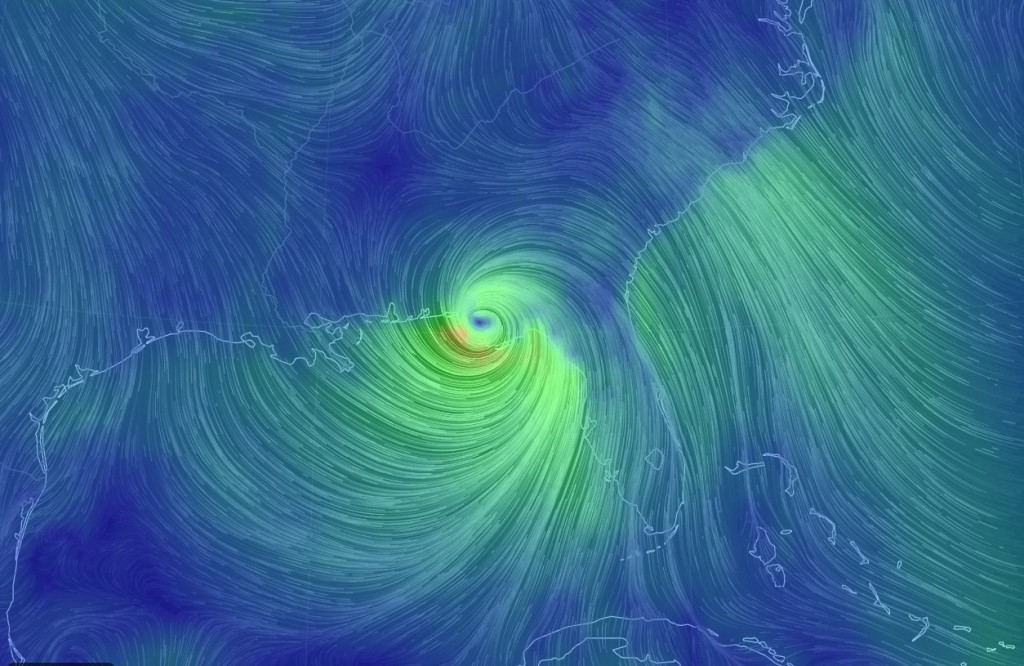

Global earth interactive wind map https://earth.nullschool.net/. This interactive map allows you to look at current winds anywhere on the earth by dragging and zooming on the globe. You can use the menu on the lower left to pick higher levels in the atmosphere; this will allow you to look at jet streams aloft as well as surface winds.

Windy global current and forecast winds https://www.windy.com/. This site provides global current and forecast winds as well as other weather information that will allow you to view the weather and plan for future weather conditions at home or away.

These sites provide you with information about both wind speed and direction. That can be very useful for gardeners who are spraying or need wind information to track where the air hitting their gardens has come from. Wind drift of agricultural chemicals also causes damage to crops and outdoor workers. Exposure to chemicals such as weed killers can affect gardens adversely, and it can be important to know where those chemicals are coming from. If you don’t have access to local wind observations, these maps can provide you with useful information.