Everyone has their favorite season. Mine is spring, because of the pop of early flowers, the hundreds of shades of green that appear as bushes and trees leaf out, and the warmer temperatures that come with the march towards summer. Winter is my least favorite because of the lack of color after the deciduous trees drop their leaves, leaving stark black branches against white clouds or snow. I admit I don’t like the cold either! Most of us talk about the seasons a lot, but what are they really? Today’s topic is how seasons are defined and how that relates to gardening.

Definitions of seasons

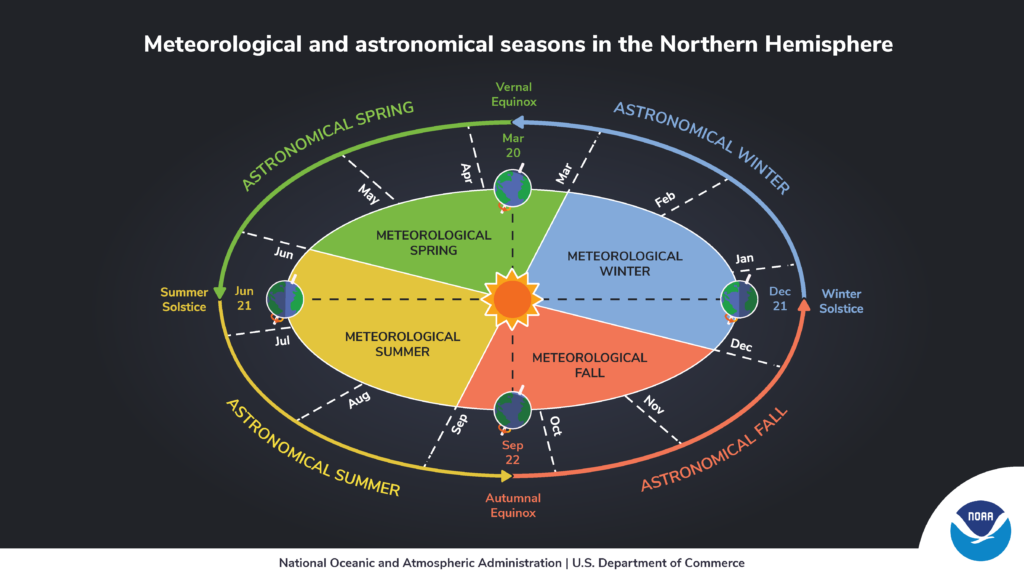

Seasons can be defined in several ways. The most common definition of a season is the astronomical season. This is related to the movement of the earth around the sun. Since the earth’s axis of rotation is tilted by 23.5 degrees relative to the plane of the earth’s orbit, the amount of sunlight anywhere on earth receives changes depending on whether the pole is tilted towards the sun or away from it. In the Northern Hemisphere, summer begins at the summer solstice, when the North Pole is pointed most directly at the sun. This is when the sun appears highest in the sky at noon, usually around June 21. The winter solstice occurs when the earth is halfway around the sun six months later and the North Pole is pointed most directly away from the sun. This means less energy is reaching that hemisphere, resulting in fewer hours of daylight and less incoming sunlight, resulting in cooler temperatures. Between the two solstices are the vernal (spring) and autumnal (fall) equinoxes, the dates on which the lengths of day and night are basically equal. They fall on roughly March 21 and September 21. As the earth progresses on its orbit around the sun, we cycle through these geometric changes, resulting in the variations of incoming energy that drive the rise and fall of average temperature over the year.

Climatologists and meteorologists define the seasons by date instead of by geometry. Northern Hemisphere winter is considered December, January, and February, spring as March through May, summer as June through August, and fall as September through November. In part, these calendar months were chosen for ease in calculating averages for monthly and seasonal climate reports in the days before calculators were available and all averages were calculated by hand. But it turns out that the calendar months are a better measure of when the warmest and coolest three-month periods occur (climatological summer and winter) than astronomical seasons are. So the seasons change for climatologists several weeks before the astronomical change of the seasons occurs. If you want to learn a lot more about different ways to define seasons climatologically, then I recommend Brian Brettschneider’s detailed article on Defining the Seasons.

Defining seasons by phenology

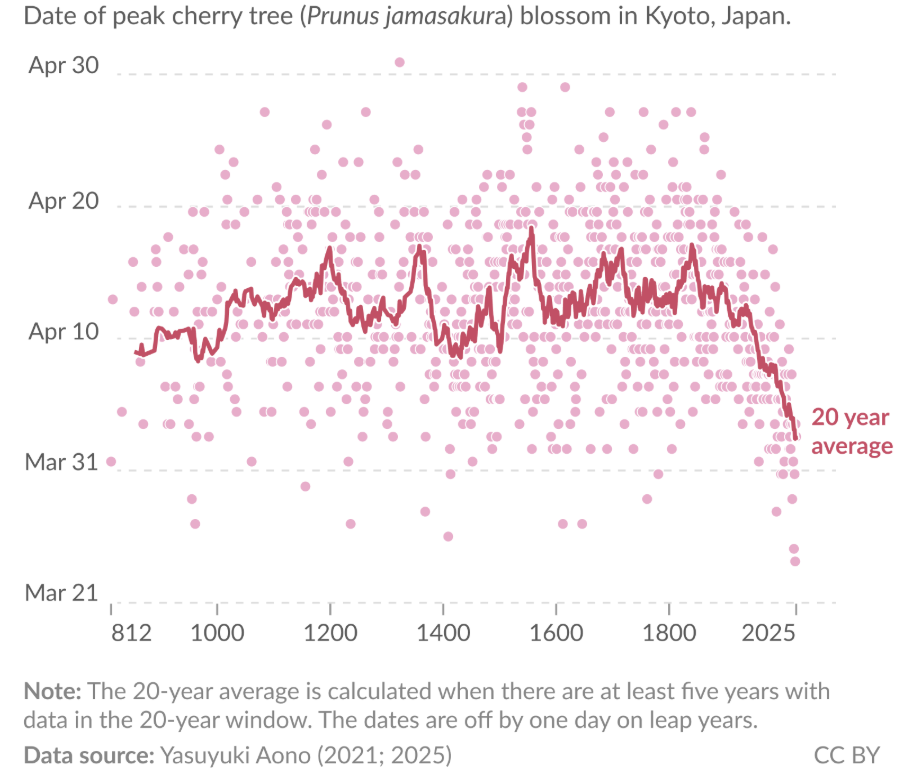

In addition to astronomical and climatological seasons, there are other ways of defining the seasons as well. One method of measuring the start of a season is through the use of phenology, the study of when a particular environmental event is observed to occur. This could be the first leaf on a honeysuckle bush, the first cherry blossom, or the first date a northern lake is frozen over in winter. Gardeners’ observations are critical in marking the change of seasons using phenology because they carefully watch the plants and animals in their local landscapes over time. The National Phenological Network in the United States is a citizen science effort underway for many years that catalogs the changing seasons by monitoring and recording a variety of phenological events as reported by gardeners and others. Many other countries have similar phenological societies that catalog the first blooms of different trees and flowers as well as changes in rivers and lakes or the appearance of migratory birds like robins for the first time each spring. Maybe some of you contribute to this effort in your own community or country. Some countries like Japan have kept records of first cherry blossoms on particular species of trees for hundreds of years and have seen how this has changed over time. This allows us to see long-term trends in climate based on based on how changes in temperature and precipitation are affecting the way plants grow.

A new phenological index: the Late Bloom Index

While many phenological studies keep track of “first” occurrences like the first cherry blossom or the first leaf on a particular type of tree, the National Phenological Network has recently introduced a new index called the “Late Bloom Index”. This index records the last occurrence in a year of a phenological event such as the last time a bloom is observed on a particular plant species. Keeping track of both the first and last bloom of a plant species gives us a deeper understanding of a plant’s life cycle as well as allowing us to track climate variations through phenology.

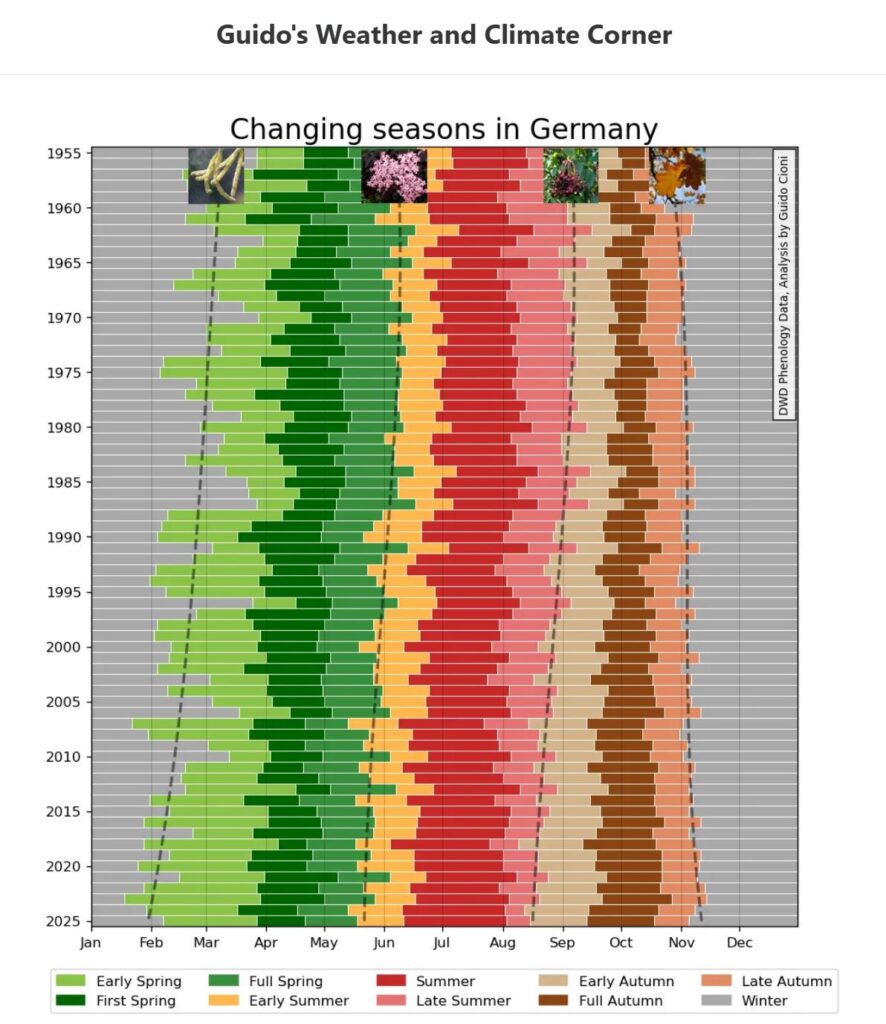

The seasons are changing

Use of phenological data has allowed us to study changes in climate in a new way. A recent study of seasons defined by the phenology of different native plants that bloom at different points in the year has shown that the seasons as defined by these plants have changed in Germany (Guido Cioni). According to their research, spring, summer, and autumn (as defined by phenology) are all starting earlier in the calendar year than they did in the past. This might sound odd, but if you think about how plants grow, it makes more sense. Once plants begin their life cycle of producing leaves, blossoms, and fruit, they progress through that life cycle on a regular schedule that is controlled by the climate that plant is growing in as well as by their genes. If spring starts earlier due to the warming climate, then the plant will grow and propagate on its own regular schedule and will finish its life cycle earlier than when the climate was cooler. This has some unfortunate consequences for insects, birds, and other animals that depend on the fruit of particular plants, since they may occur earlier in the year than in the past and that may not match the needs of those animals for migration or preparing for hibernation.

The seasons of your garden

If you don’t already keep a journal of what you are observing in your garden, I encourage you to start. That is a great place to keep track of how your plants (and insects and birds and wildlife) are changing over the year. If you live in the same place for long enough, you will have a historical record of how your local climate is changing and a source of enjoyment at how weather and climate may be impacting your garden’s growth from one year to the next. You may even wish to provide your observations to the NPN using their Nature’s Notebook program. That will allow you to compare your own observations to other gardeners around the country and the world. You can be a scientist as well as a gardener!