Nothing is more frustrating to a gardener than watching a newly installed tree or shrub slowly die. In performing “post mortem” analyses on failed landscape plantings, I’ve identified four common errors that can be easily avoided:

- inadequate root preparation

- improper soil preparation

- planting below grade

- inadequate aftercare

This blog entry will be dedicated to the first point – but before I do so, we need to understand how nursery plant production has changed over the last several decades.

A brief history of propagation

Many years ago the only way to obtain young trees and shrubs was as bare-root plants. Plants were field grown, then dug up during dormancy for storage and shipping. Bare-root trees and shrubs are usually only available during a narrow window of time, but in general these plants are healthy and structurally sound. Most importantly for our discussion, growers can see the woody root system of bare-root plants and cull those that are not well formed.

The development of containerized production methods meant that plants could be grown and sold year around. When plants are grown in a production greenhouse, they are generally started in small liner pots and gradually moved through a succession of increasingly larger pots. Ideally this is done before roots become potbound, or the roots are corrected when “potted up” (moved to a larger container). What we found, unfortunately, in a study of nursery plant quality, is that root systems are often ignored in an effort to produce large quantities of plants quickly and cheaply. It is not considered to be cost effective to examine and correct root flaws during potting up, so the entire root mass is moved into the new container. Structural root flaws are not self-correcting and will become more severe the longer they are ignored.

Based on our study, as well as evidence collected by numerous researchers and arborists, it is apparent that poor root quality is a significant problem in containerized and balled-and-burlapped trees and shrubs, at least in this part of the country. Therefore, we need to correct root flaws before installing woody plants into the landscape.

A quick intro to correcting poor root systems

Balled-and-burlapped plants have a clay rootball; despite its appearance, it is fairly easy to remove the clay simply by removing the burlap and twine and soaking the entire rootball in water. You can facilitate the process using your fingers to work out the clay, or use a gentle stream of water (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Once the clay is removed the root system can be evaluated. If you find woody roots that are circling, girdling, or in general not growing horizontally and away from the trunk (Figure 2), they should be pruned (Figure 3). You want to develop an evenly distributed structural root system.

Figures 2 and 3 – before and after

The pictures in this post are from my own Cercis tree, which I planted in April of 2004. This is not a great time for planting, since Seattle has notoriously dry summers. Nevertheless, that’s when I planted and as you can see from Figure 3, I had to remove close to 70% of the root system. I mudded it in well (which eliminated the need for staking), mulched, and kept the root zone well rooted. It sat for about 3 months and did nothing (Figure 4), except of course the flowers died quickly!. In July it leafed out (Figure 5), and 3 years later had doubled in size (Figure 6). It is now close to 15 feet tall and is in excellent health. Given its initial root system, it’s doubtful it would have done this well without intervention.

Figure 4 – April 04 Figure 5 – July 04 Figure 6 – July 07

(I have performed radical surgery on hundreds of tree and shrub root systems and have only lost one small shrub, whose root system is in Figures 7-8. Kind of tough to prune something as fatally flawed as this.)

Figures 7 and 8 say so much more than I can.

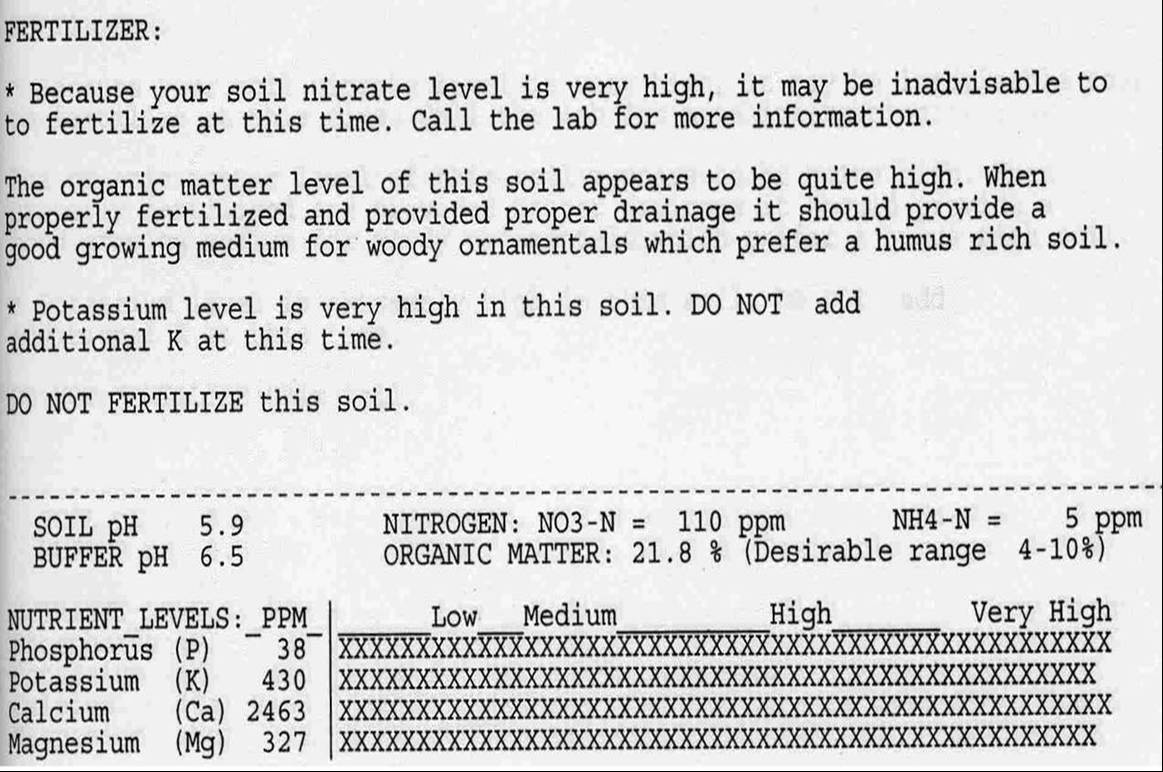

Figure 1. Note the high level of organic material in this soil, which contributes to the nutrient overload.

Figure 1. Note the high level of organic material in this soil, which contributes to the nutrient overload.