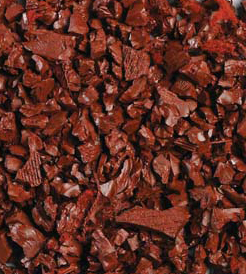

I’ve been receiving a lot of questions about rubber mulch lately. For those of you not familiar with the product, it consists of shredded tires that can be dyed and used on ornamental landscapes or under playground equipment. In fact, the Obamas had this material installed underneath their children’s play structure at the White House. It seems an ideal way to recycle the 290 million scrap tires we generate annually.

But is it?

It’s not effective: One of the main reasons we use mulch is to suppress weeds. Research has demonstrated that organic mulches such as wood chips, straw, and fiber mats control weeds better than rubber mulch.

It burns: You’ve heard stories about piles of scrap tires catching fire and burning for weeks. Well, those same flammable compounds are in rubber mulch, too. When compared to other mulch types, rubber mulch is the most difficult to extinguish once ignited. In fact, some parks and playgrounds no longer use rubber mulch or rubberized surfaces because vandals have figured out that rubber fires cause a LOT of damage.

It breaks down: Although sales literature would have you believe otherwise, rubber is broken down by microbes like any other organic product. Specialized bacterial and fungal species can use rubber as their sole food source. In the degradation process, chemicals in the tires can leach into the surrounding soil or water.

It’s toxic: Research has shown that rubber leachate from car tires can kill entire aquatic communities of algae, zooplankton, snails, and fish. While part of this toxicity may be from the heavy metals (like chromium and zinc) found in tires, it’s also from the chemicals used in making tires. These include 2-mercaptobenzothiazole and polyaromatic hydrocarbons, both known to be hazardous to human and environmental health.

It’s not fun to be around: When rubber mulch gets hot, it stinks. And it can burn your feet. Yuck.

The EPA’s website says this about scrap tires: “Illegal tire dumping pollutes ravines, woods, deserts, and empty lots. For these reasons, most states have passed scrap tire regulations requiring proper management.” So if we have legal tire dumping (in the form of rubber mulch), does that mean it doesn’t pollute anymore?

(You can read a longer discussion on rubber mulches here.)

Don’t have a photo of the Magnolia-eating creeper, but I do have this nice truck-eating ivy.

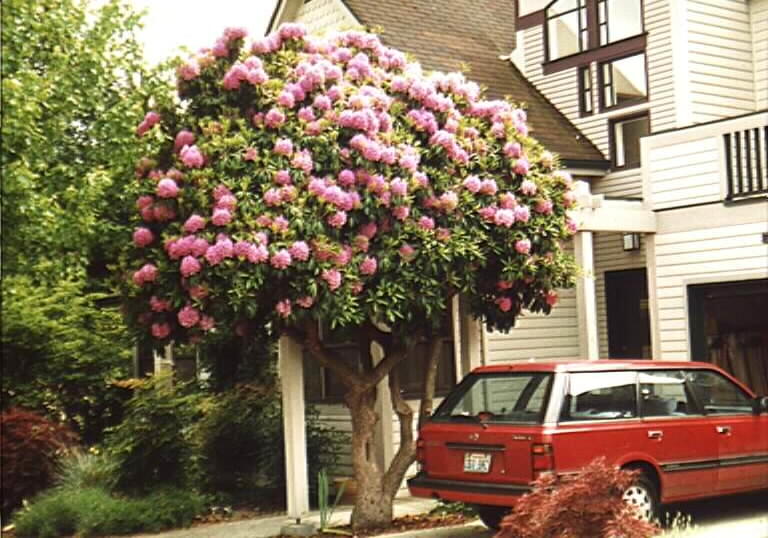

Don’t have a photo of the Magnolia-eating creeper, but I do have this nice truck-eating ivy. Sidewalk-eating Japanese maple – not an invasive, but easily outgrows its “expected” space

Sidewalk-eating Japanese maple – not an invasive, but easily outgrows its “expected” space