Herbicide issues seem to be dominating my life these days. Over the past several weeks reports have surfaced around the Midwest of landscape conifers – primarily spruces and pines – that have developed rapid and severe die-back. While there are a host of insect pests and pathogens that can cause die-back in conifers, the recent cases are noteworthy in the speed with which trees expressed symptoms.

Photos: Andy and Carol Duvall

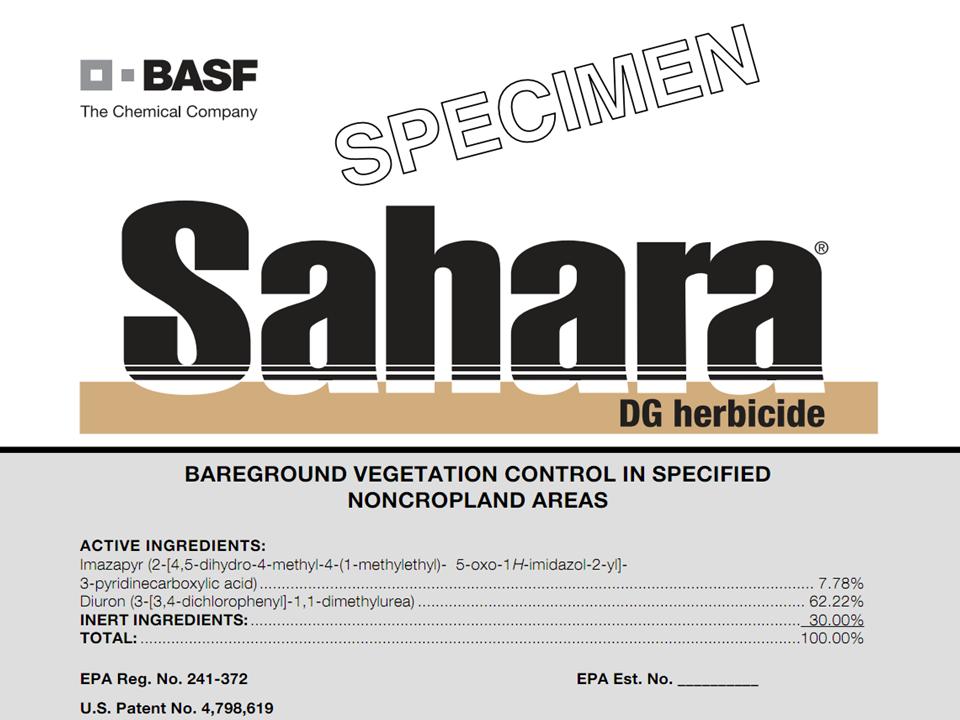

In many cases that have been reported the common thread appears to be the use of Imprelis, a turf herbicide developed and marketed by Dupont. Imprelis (active ingredient: aminocyclopyrachlor) is a synthetic auxin designed to control broadleaved weeds in turf. Ostensibly, one of the advantages of Imprelis is that has root activity in addition to foliar activity. It appears, however, that it may have too much root activity and the internet is abuzz with photos and posts of Imprelis-damaged conifers. http://bestlawn.info/northern/imprelis-and-dupont-trouble-t4608.html

http://www.buckandsons.com/blog/tag/dupont-herbicide-imprelis/

So what’s going on? Well there are lots of blurbs coming out and lots of things being reported second and third-hand. I suspect a few things we ‘know’ about Imprelis right now will turn out not to be the case in a few months. Dupont has tried to shift blame to the applicators, suggesting that their rates may have been off, they applied when there was potential for drift, or that the material was mixed with other herbicides. http://www.ksuturf.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/DuPont-Letter-to-Turf-Professionals-061511.jpg

Given that reports of damage showing similar symptoms have come from Kansas, Iowa, Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio it seems unlikely that everyone is mis-applying the product. I suspect one of a couple things may be going on. Dupont may have underestimated the lateral extent of tree roots, especially for conifers that often have shallow, extensive root systems. It’s also possible that Norway spruce and white pine are more sensitive to this product than whatever Dupont tested it on.

In the meantime stay tuned. In case people haven’t figured it out for themselves, Dupont now recommends that applicators not use Imprelis near spruces or pines (see letter linked above). Landscapers or lawn service operators that have applied Imprelis should keep in touch with their state Department of Agriculture and their professional turf and landscape association. Might be good to fasten your seatbelts, this could be a bumpy ride…