The cooler weather that many parts of the eastern United States are experiencing this week is causing many gardeners to think about what this fall will be like. In fact, many farmers in Georgia are already planting fall crops, and I am sure that many gardeners are also busy with their own fall planting if they live in the Northern Hemisphere mid-latitudes. In this blog post we will discuss seasonal forecasts and how you can use them to plan and plant your garden.

What kinds of long-range forecasts are available?

In weather and climate, there are two basic types of forecasts. The first is a deterministic forecast, which gives an outlook that describes the specific weather that is expected to occur at a discrete time in the future. Deterministic forecasts are commonly used for weather forecasts for the next few days and are based on computer model predictions that are grounded in the physical equations of motion, thermodynamics and other properties of the atmosphere. Generally, deterministic forecasts are most useful within a few days after the forecast is made. As you go farther out in time, they become less accurate due to lack of updated weather observations and drifts in the models due to the chaotic nature of the atmosphere. In general, a deterministic forecast is not very accurate more than a week ahead of when it is made. They are better than they used to be, and the accuracy of a 7-day forecast now is as good as a 5-day forecast was a couple of decades ago, but we will likely never have a perfect deterministic forecast more than ten days out.

Longer-term forecasts are usually given as probabilistic forecasts. In other words, the forecast will give a likelihood of occurrence of general weather conditions such as wetter or drier and colder or warmer than normal. For meteorologists, “normal” is a 30-year average of temperature and precipitation at a location and is currently based on the 1991-2020 period (they are updated every ten years due to the amount of work it takes to produce a clean dataset). Most probabilistic forecasts are based on multiple model results that start from slightly different conditions and are built with different methods of creating rain and clouds, moving temperature and humidity around, and start with different surface conditions. The more the models agree, the higher the probability of occurrence of a particular type of weather.

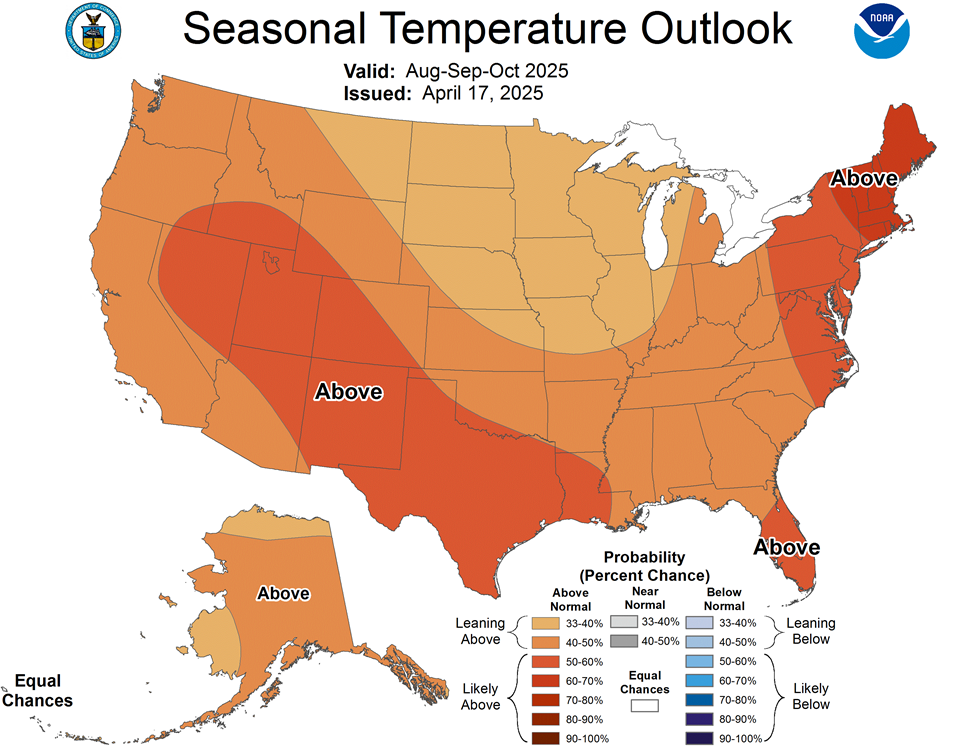

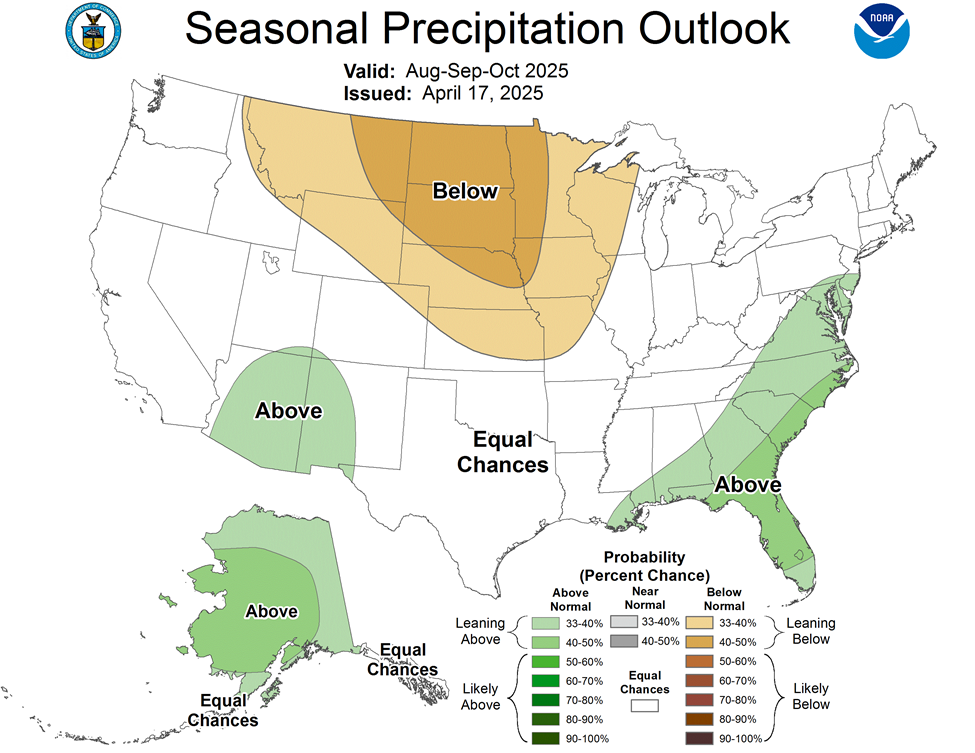

How to interpret the NOAA monthly and season forecast maps

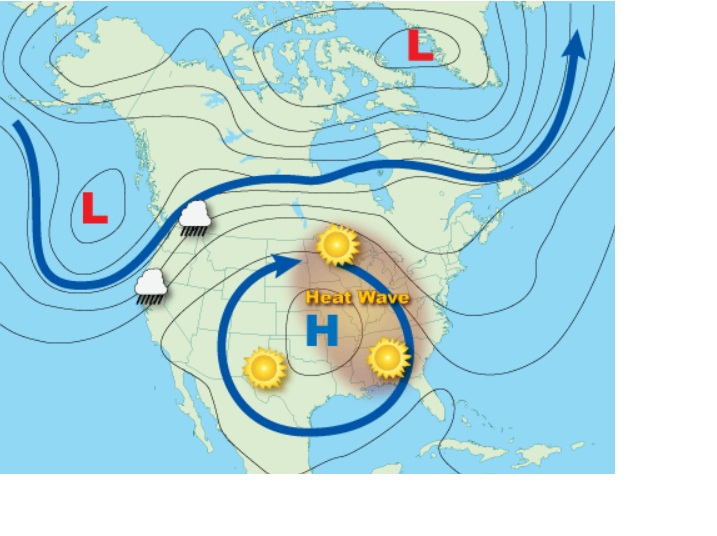

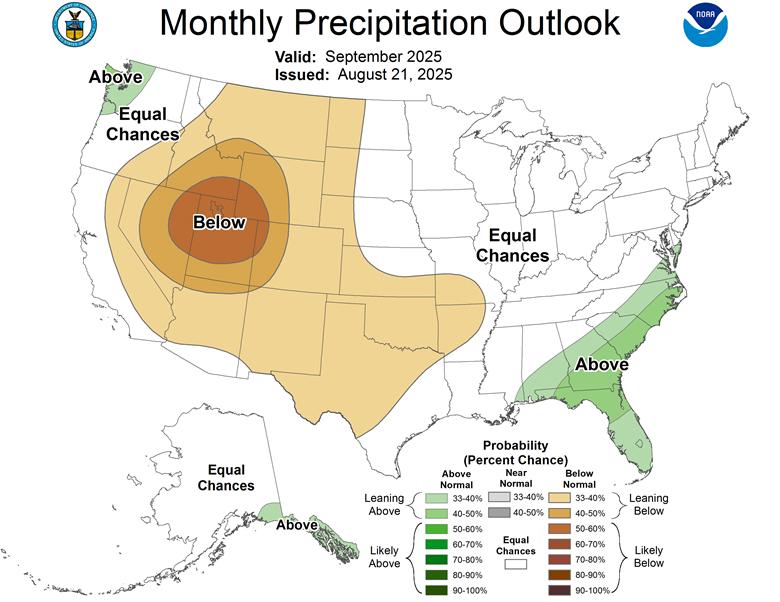

In the NOAA map for September 2025 above, for example, there is a dark brown area centered on the Great Salt Lake in the western United States. This is an area that has a strong probability of being drier than normal in the month of September based on the available model output. The fact that it is dark brown does not mean it will necessarily be much drier than normal, but that we have a strong likelihood that it will in the lowest third of years in terms of how many inches of precipitation it is likely to experience. These forecasts start from even odds of having near normal precipitation (34%), above normal precipitation (33%) and below normal precipitation (33%). If the climate forecast models indicate mostly dry conditions at a point, then the percentages shift to something more like 34% near normal, 50% below normal, and 16% above normal precipitation. Because there is so much uncertainty in the atmosphere, you never know with total accuracy which category the season will fall into, you just have some confidence of which way it is likely to fall. Since this is the average for an entire month or season, there can be periods within that time span that are significantly different weather that what the probabilities suggest are the most likely to occur. Here is a list of what the seasonal forecast maps do NOT tell us.

Deterministic versus probabilistic forecasts

If you are planning an outdoor event like a garden wedding months ahead, a deterministic forecast is what you would probably want to know. Do we need to rent a tent? Should we expect hot or cold weather when we purchase a dress? Unfortunately, this is not possible a long time ahead and so you need to use previous or average weather conditions on that date to decide what kind of weather is most likely to occur and be aware that you could be wrong. There are a few commercial forecasting sites that provide specific deterministic forecasts up to 90 days ahead. I asked a friend who works for one of these companies why they do it when research shows that there is no skill involved, and he told me they do it for “entertainment value.” In other words, it is not real information, it is just click-bait. The same thing happens with wild hurricane forecasts on social media that show a single deterministic forecast of a huge storm hitting somewhere like Tampa, conveniently not showing the 99 models with no such storm present. Don’t believe them, they are harvesting clicks, not providing useful information.

The Farmers’ Almanac and the Old Farmer’s Almanac

Every year, including this one, publishers release almanacs each fall which claim to show what the weather will be like for 1 to 3-day periods for the winter and next year. Their winter outlook maps get a lot of press about what to expect weatherwise for the next few months (I won’t post any links in this post but you can search online if you are really curious). If you read them carefully, you can see they are quasi-deterministic since they reference storms or heat waves occurring at specific areas over just a few days, although they are usually written in broad enough language that they can be interpreted in several ways. Many people use these for planning their gardens, and they do contain useful information about climatological conditions, average frost dates, and sunrise and sunset information. But scientists have shown that they are only about 50% accurate, which amounts to pure chance. They base their forecasts on secret formulas that cannot be scientifically studied or verified so we have no way to know what they are really using to determine what those forecasts will be. So if you buy one this year, I challenge you to keep track of what they forecast and what weather actually occurred at your house and see if they did any better than chance in 2026. Let the buyer beware and use them for “entertainment value” only.

What can we expect this fall?

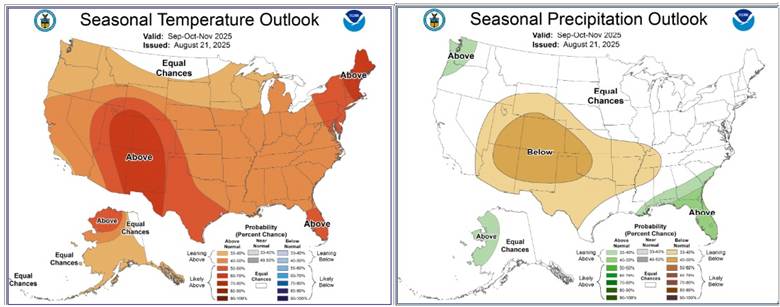

Based on NOAA’s probabilistic forecast, we can expect the temperature across most of the United States to be warmer than normal, with some areas more likely to be warm than others. This is likely due to the continuing greenhouse warming that is occurring, making every year (on average) warmer than the previous one, although there is a lot of variation within that trend from one year to the next. Precipitation in the Southeast for the September through November period is leaning towards wetter than normal conditions, and that is probably related mostly to the second half of the Atlantic hurricane season, which could bring heavy rain to parts of the Southeast during fall even though parts of it will certainly be missed. The southwestern United States centered on the Four Corners area is expected to be drier than normal in an area that is already quite dry climatologically.

For the December through February period, the forecast is showing a pattern of climate conditions that is consistent with the La Nina that is expected to occur as we head into winter, with warmer and drier conditions in the southern US and wetter and cooler conditions in the northern US. If you live in a different part of the world, you can find images of the expected La Nina conditions here. Choose plants according to the climate conditions you expect and be prepared to manage them for those conditions, so that if you are in the South, you may have to water more frequently because of the drier than average conditions.

Seasonal outlook maps can provide clues to the kind of temperature and rainfall conditions you are likely to experience in your neighborhood over 3-month periods, although they will not give you specific details about when the first frost might occur or how many heavy rain events you can expect to see. But knowledge of the likely pattern of conditions you can expect will allow you to plan what kind of plants to put in the ground and how you are likely to have to take care of them as they grow.

Just an additional note: If you like to track the fall colors, check out this interactive fall foliage map at https://www.explorefall.com/, now including Alaska. It’s a great resource for planning weekend trips to areas you think will be experiencing beautiful fall foliage.