The holiday season creeps earlier and earlier each year, at least here in the US. Decorations, trinkets, and more start filling store shelves before summer is even over. But some holiday traditions can’t be rushed, like live holiday plants. Many of these picky plants have to be bought and cared for closer to the holidays, else they likely won’t look so festive once the holiday finally arrives. Since the origins of many of the holiday traditions are pagan and druid in nature, it stands to reason that plants are a major theme for the holidays. I’ve written before about the origins of using the plant parasite mistletoe as a holiday decoration and invitation for lip locking. And also about how what most people call a Christmas cactus is actually a Thanksgiving cactus and they are actually two different things (and there’s also a Spring/Easter cactus as well. We have amaryllis, paperwhites, cyclamen, Norfolk Island pines, pine-shaped rosemary plants, and more that make up our usual holiday decor. But none are so vibrant and indicative of the holiday as the poinsettia. So let’s talk a little about the history and lore of this plant and also about how day length affects its colorful holiday display. Just in case you want to try saving one from year to year.

What is a poinsettia, anyway? It doesn’t really look like other plants.

This plant is a standout in the mostly weed-filled and much-maligned spurge family Euphorbiaceae. This family includes lots of different plants that take on a variety of forms. It does include many weeds, but also many houseplants that have much more of a cactus form than poinsettia. Relatives you might find as houseplants include a cactus-like plant with leaves on its margins (mainly just called Euphorbia), a plant called crown of thorns and a sticklike plant called pencil cactus. It is a weird family. Most of them do have a sap that can cause dermatitis in the skin or a stomach ache if ingested. But poinsettia has earned an incorrect reputation as being poisonous and a plant to steer clear of if you have kids or pets. Sure, ingestion might cause a tummy ache and associated symptoms, but the amount of poinsettia one would have to eat to actually have life-threatening symptoms is astronomical.

While we enjoy poinsettias for their bright colors, it would be incorrect to say that poinsettias have large, colorful blooms. The colors that we see are called bracts — brightly colored leaves. These bracts change color much the same way leaves change color in the fall: They lose their green chlorophyll to expose the color beneath. This happens when the flowers, those ugly little yellowish lumps in the middle of the bract, mature.

While the classic red poinsettia (pronounced poin-SEH-tee-uh, not poin-SEH-tuh, by the way) lends itself to the classic colors of Christmas, it might be hard to figure out how this weed from Mexico found its way to the top of the list of traditional holiday plants. After all, it is a much more recent addition to the holiday decoration arsenal than the evergreens borrowed from ancient pagan rituals. And while we most often think of red poinsettias, there are hundreds and thousands of different cultivars and colors – and we’ve even taken to spraying them with dye and glitter (shudder).

Poinsettias are famous for having a difficult blooming process. The plants are considered short day plants, thought the more accurate description would be a long night plant. This means that in order to set blooms, the plant needs a few weeks where it receives at least 12, and preferably 16, hours of uninterrupted darkness each night. This creates physiological and chemical cues that allow for development of floral structures, which in turn result in development of the colorful bracts. Even a few seconds of light in the middle of the night can stop, interrupt, or delay the process. This often makes saving poinsettias from year to year difficult, and can even make it difficult for commercial growers to provide darkness in our ever (artificially) brighter night sky.

How did a weed get associated with Christmas?

The poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima) is a native plant (and can grow as a fairly large shrub or tree) in Mexico. The original name used for the plant, prior to Americanization, was cuetlaxochitl. I’ve seen them in several places around the world, including one as big as a tree in Kigali, Rwanda (other Euphorbia, like the pencil cactus also grow there). A local Mexican legend from the 14th century explains that a young girl on her way to Christmas Eve mass was upset that she had no gift for the baby Jesus and picked a handful of weeds on her way to church. As she placed the humble bundle of weeds on the altar, they erupted into brilliant red, and all those around exclaimed that it was a Christmas miracle.

Aside from the miracle legend associated with the flower, there are other connections between the plant and the holidays. The traditional red of the poinsettia is cited by many as a representation of a blood sacrifice and the shape of the flower as the Star of Bethlehem. Before poinsettias became a worldwide symbol of the holidays, Franciscan friars included the vivid plants in Christmas celebrations in the 17th century. In Mexico, the plant is also known as Flor de Nochebuena, or Holy Night (Christmas Eve) Flower.

From ditchweed to international holiday superstar

The poinsettia really didn’t come into its current fame until it was introduced to the United States in 1825, at the hands of a politician. It just so happened that the first U.S. minister to Mexico (this was before we had ambassadors) was an amateur botanist. He brought the plant back to his private hothouses in South Carolina, and then shared it with friends (including renowned botanist John Bartram) who introduced the plant to the nursery trade. It filled an empty spot in the nursery calendar, so nurseries were quick to embrace the plant.

The plant quickly was renamed Poinsettia (it was originally sold under its botanical name) in honor of the man who brought it to the country — Joel Roberts Poinsett. His contribution to the plant’s history and the nursery business in the U.S. was honored by Congress, which has declared Dec. 12 National Poinsettia Day. A date which, oddly, commemorates the date of Minister Poinsett’s death.

Aside from his botanical triumph and service as minister to Mexico, Poinsett was also an “agent” to Chile and Argentina, a state representative, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives and secretary of war. Most people would be surprised to learn that the man who brought you the poinsettia also oversaw the removal of Cherokees from North Carolina to Indian Territory in 1838 and the military during the second Seminole War. But he was also involved in the Columbian Institute for the Promotion of Arts and Sciences and a co-founder of the National Institute for the Promotion of the Sciences and Useful Arts.

This national institute, composed of politicians, promoted the use of the Smithson bequest to form a national museum. While they were defeated in their efforts, the institute went on to become part of the result of the Smithson bequest — the Smithsonian Institution.

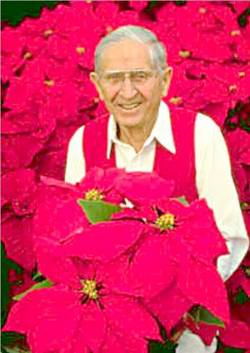

The poinsettia didn’t become common holiday fair for the general masses until Paul Ecke Sr., a German immigrant living in California started growing them on a large scale. Ecke and family were also responsible for breeding poinsettias, turning them in to a weedy plant in to the more robust, bushy form we see today. While the Ecke family has moved a lot of production overseas, they are still responsible for 70% of the poinsettias sold in the US and nearly half of all poinsettias sold worldwide.

(1895-1991)

So, how can I save my poinsettia and get it to rebloom next year?

In theory, this is pretty simple, but as GP alum Holly Scoggins points out it can be difficult to keep these plants happy and healthy, let alone get them to rebloom so that the bracts will color up.

But if you do want to save your poinsettia from year to year, here’s how to do it:

- Keep your poinsettia in a bright but cool spot to keep it colorful longer. When the leaves start to yellow, or you are done with it for the season, slowly reduce watering until it loses all leaves (and colorful bracts, which will be last to go) and goes dormant.

- Store the plant in a cool (50-60 F), dry, and dark area. Keep the soil on the dry side, but water just enough to keep the stems from drying out.

- After the danger of frost has passed, or in April or May (if you don’t have frost), remove the plant from storage and repot. Use a good quality and light soil mix – poinsettias do not do well with heavy soils. And it turns out that since poinsettias are typically sold as disposable plants, the soil they come in is crap (even high end houseplants these days come in cheap, crappy soil). Practice root washing to remove all the old soil and pot up to a larger size if the plant seems root bound.

- Place the plant outside if possible after the danger of frost has passed, or grow in a bright, sunny window. Keep humid, well watered, and fertilized throughout the growing season.

- As the danger of frost approaches, move the plant indoors in a bright, sunny window (if it isn’t kept indoors). Ideal temperatures are 75F during the day and 60-65F during the night.

- In late September or early October, move the plant to an area that receives no light at night, even from outdoor street lights. The easiest way to provide exact light and dark needs would be in a dark room with lights on a timer. Provide no fewer than 12, and preferably 14-16 hours of uninterrupted darkness and 8-12 hours of light per day. Alternately, you can move the plant to a dark room or closet for its dark period.

- After flowers begin to form and bracts start to change color, move to a preferred place in the home for the holidays. Continue to keep the plant well watered, and regularly fertilized through the holiday season.

- Rinse and repeat, if desired.

Sources:

NMSU Extension – Poinsettias: Year after Year

Ambius – The long, strange tale of the poinsettia

UMN Extension – Growing and caring for poinsettias

Investors.com: Paul Ecke Sr: ‘Poinsettia King’ Cultivated a Holiday Tradition