While the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) continues to expand in the upper Midwest (see http://www.emeraldashborer.info/files/MultiState_EABpos.pdf for a current infestation map), EAB is old news here in Michigan, especially in the southeastern part of the state. Efforts to restore urban and community forest canopy lost to EAB will continue, however, for the foreseeable future. In 2003 we established an Ash Alternative Arboretum MSU Tollgate Education Center in Novi, MI – which is near ‘Ground Zero’ for the EAB infestation in North America.

The planting offers some insights into selecting alternative landscape trees to replace ashes. A couple of elm cultivars, in particular, have emerged as shining stars in the demonstration planting that includes five specimens of 37 different species and varieties. All trees were planted as 1½”-2” bareroot liners by Tollgate volunteers. Tollgate farm manager Roy Prentice has overseen the maintenance of the planting.

Accolade elm (Ulmus japonica × wilsoniana ‘Morton’) Compared to most of the other selections planted in the arboretum at Tollgate, Accolade elm looks like a man among boys. Growth of these trees has been outstanding – the trunks of the trees have grown fast enough that they have split off their plastic rabbit guards (see photo). Like Triumph elm, Accolade elm has dark green glossy leaves and develops into a large tree. Although elms are often thought of ‘ugly ducklings’, both Triumph and Accolade are quickly developing well-formed vase-like crowns.

Triumph elm (Ulmus ‘Morton Glossy’) has also done very well at the Tollgate planting. This elm develops a vase-like crown with age and has dark green, glossy leaves. A large tree to 55’.

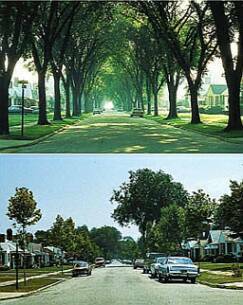

The elms are part of series of elm cultivars that have been developed with high tolerance of Dutch elm disease. Most of the new elms are hybrid crosses with Asian and European elm species, though selections of American elm that are tolerant of Dutch elm disease are also available in the nursery trade. The irony in all of this, of course, is that native American elms were devastated by another introduced exotic pest, Dutch elm disease. As elm trees were rapidly lost during the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s, ash trees became a popular replacement due to their ease of transplanting, growth rate, broad site tolerance and pest resistance (yet another irony). Now we’re promoting elms to replace ashes.

Street scene before and after Dutch Elm Disease. Photo: theprincetonelm.com

The moral of the Dutch Elm Disease and Emerald Ash Borer stories is that it’s critical to avoid over-reliance on one species or even one genus – even a native one. In Michigan some of our urban and community forests are over 50% maple. As global trade increases and the potential for destructive pests to hitch-hike around the world rises, the best hedge against catastrophic tree loss is to plant a broad and diverse array of adapted trees.