Long-time followers of this blog know that I’ve been researching, writing, and educating on the topic of landscape mulches for over 20 years. So whenever an article comes out in a newspaper or online that directly refutes our current understanding of mulch science, on-line and real-life colleagues quickly call it to my attention. Many times I choose to ignore the article, but when it’s from a highly regarded source with wide readership I feel the need to step in. Before I discuss the problematic statements, I want to explain part of my process in determining whether an expert is really an expert.

Here are two questions I ask:

- Is an expert regarded as an expert in the area of interest by other academic experts?

- Is there published research provided that supports statements that don’t agree with the current body of knowledge?

If the answer to both questions is no, then the source cannot be considered reliable.

To the writer’s credit, she seeks out academic sources for her information. Her source has stellar credentials in researching and educating about compost, but has no publications on mulching or mulch materials (Question #1 = no). And there are source quotes and author statements throughout the article that are not supported with evidence (Question #2 = no).

I’ve identified the misleading or erroneous statements and quotes below with my rebuttals. I have included linked references at the end that address these points in more detail. And we have dozens of posts on mulches in this blog’s archives.

1. “In a forest…there is no big heap, just a layer of an inch or two or three, breaking down and returning to the system.”

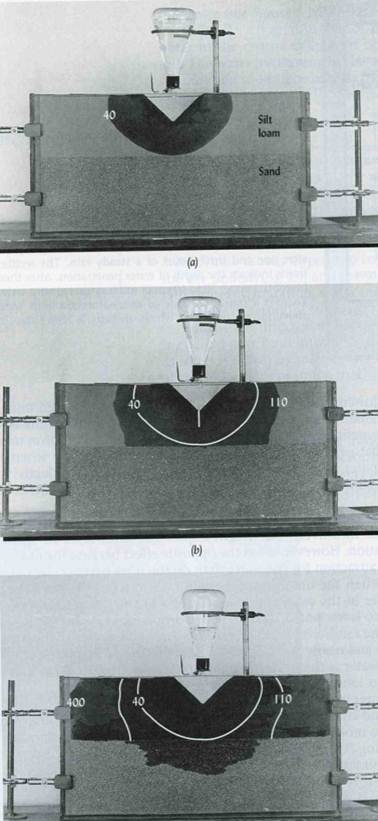

Observations of relatively undisturbed forest floors reveal deep layers of woody debris, leaves and needles, and other materials falling from the canopy. Research has shown that a minimum of 3 inches of a coarse textured mulch are needed to restrict sunlight from reaching the soil and prevent weed seed germination. Any less than this will enhance, not prevent, weed growth. Deep layers of wood chips have been repeatedly shown to suppress weeds and enhance the health of desirable plants.

2. “The process releases humates…described as ‘black, gooey liquid’…”

Humates, defined as recalcitrant materials that resist further decomposition, don’t exist in natural landscapes. The only place you find humates are in the lab, where analysis of organic material with an alkaline reagent (pH = 12) produces humus as a byproduct. And on garden center shelves, where heavily marketed humic acids, fulvic acids, and humates are located.

3. “The only difference in mulches, as long as you use organic materials, is the rate at which they decompose”

This needs clarification. Rapidly decomposing mulches release high levels of nutrients in a short period of time; slowly decomposing materials release low levels of nutrients over longer periods of time. Compost falls into the first category, and readily available nutrients from any source can lead to nutrient toxicity in soils and imbalances in plants.

4. “In formal beds…fine- to medium-textured material”

For best oxygen and water movement, mulches should be coarse and chunky. Sawdust and compost, for example, are too finely textured to allow for gas transfer and water movement, plus weeds easily establish on top of compost.

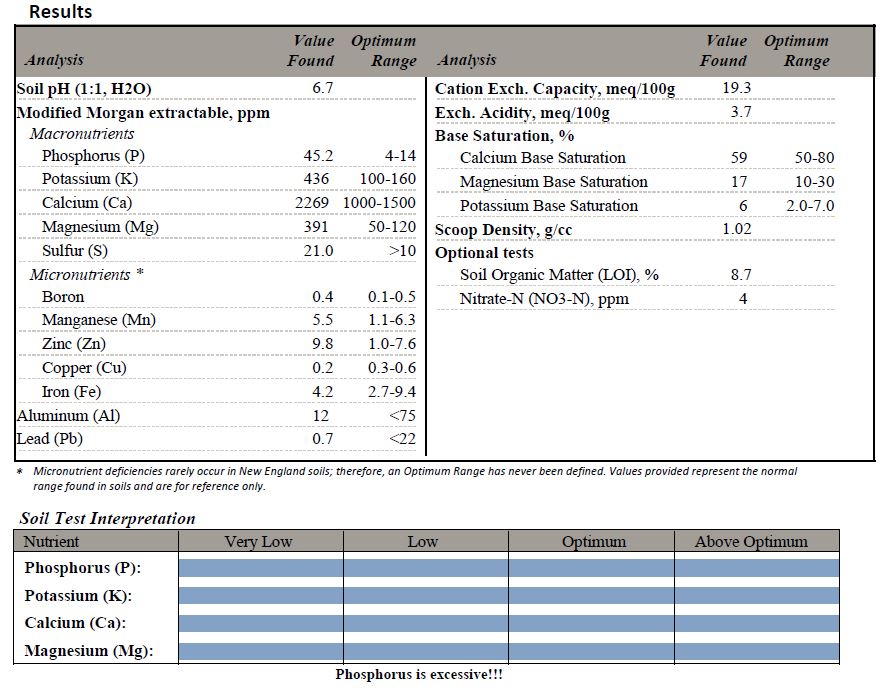

5. “If a bed needs compost, spread an inch before mulching”

This statement needs clarification. The only way you know whether compost is needed is to have the results of a soil test showing an overall low level of nutrients. Then a layer of compost could be added before chips are applied.

6. “Save…the chunks fresh out of the arborist’s chipper for pathways…Or at least pile them up to mellow before you use them.”

You don’t need to compost your arborist chips. They provide a burst of nutrients during the first month, when leaves are rapidly decomposed. Using older chips is fine, of course, but why waste that early nutrient boost to your soils?

7. “If supplemental fertilizer isn’t applied when your piling on coarse, fresh, carbon-rich wood chips…it can cause some drawdown in soil nitrogen.”

Fertilizer should NEVER be applied unless there is a demonstrated nutrient deficiency, and wood chip mulches do not cause a drawdown in soil nitrogen. This myth has been dispelled by years of research showing no change to soil nitrogen covered with wood chips.

8. “Generally, mulch is applied in ornamental beds at a depth of one to three inches”

See point #1. This is not a science-based recommendation.

9. On volcano mulching: “In addition to promoting bark decay, it causes the tree’s roots to grow up into the mulch layer, rather than down into the soil…the tree may eventually die, and even topple.”

This classic correlation-elevated-to-causation is getting tiresome. There is NO published evidence, anywhere, that proper mulches (i.e., coarse arborist chips) are going to injure bark. They do not cause bark decay. Furthermore, tree roots grow where they have water, nutrients, and oxygen. This might be in the mulch layer. Growing deep into the soil is unlikely (not enough oxygen) unless the soil is excessively sandy or otherwise well drained. Any toppling of trees can be directly correlated with poor planting techniques that prevent roots from contacting and establishing in the site soil.

From an earlier Garden Professors post

10. “Keep the mulch at least several inches away from tree and shrub trunks.”

Why? Does this happen in nature? No. Per point #9, a natural woody mulch is not going to hurt trunks.

11. “And don’t invite rot by smothering the crowns of perennials”

A good arborist chip mulch is not going to “smother” anything. Perennials are quite capable of growing through several inches of woody mulch, which also protects the crowns from freezing temperatures.

If we are going to encourage gardeners to use nature as a guide (see point #1), then points 4-11 are, well, pointless.

Literature

Chalker-Scott, L., and A.J. Downer. 2018. Garden myth busting for Extension educators: reviewing the literature on landscape trees. Journal of the NACAA 11(2).

Lehmann, J., Kleber, M. The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 528, 60–68 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16069