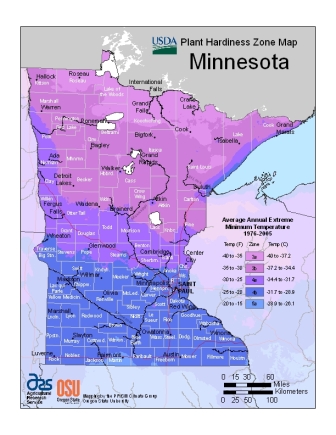

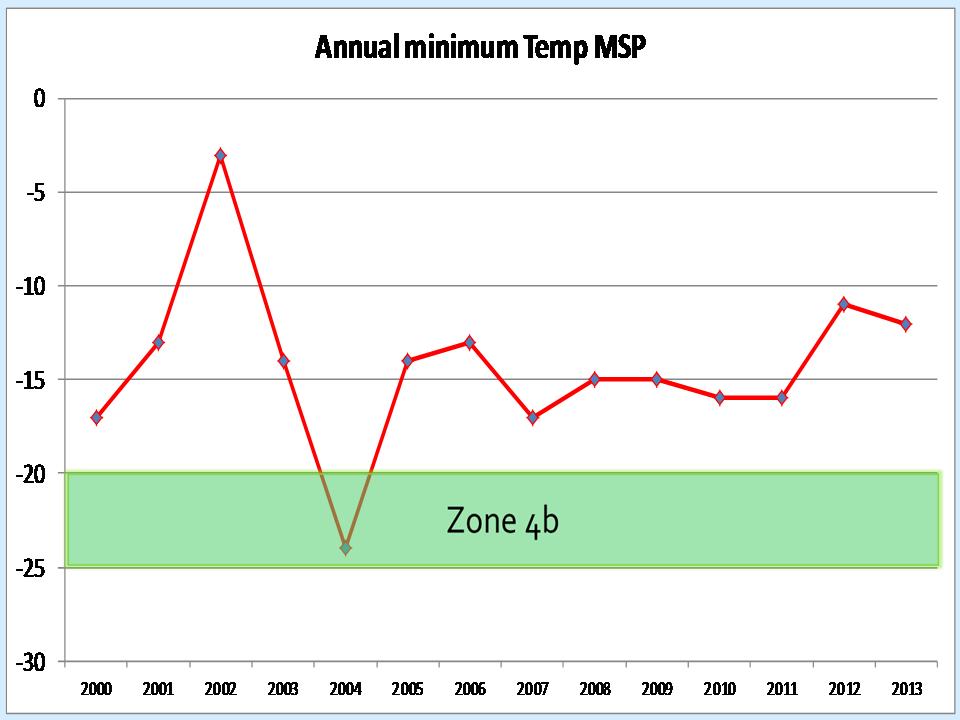

Practically the first thing a budding gardener (at least in the US) learns is their USDA winter hardiness zone. Based on average winter low temperatures, hardiness zones have many flaws but are still a very useful tool in figuring out what plants can and cannot survive your particular winters.

Right after learning about winter hardiness zones, we generally hear about microclimates – the idea that small precise locations within our garden may be, sometimes significantly, warmer or colder (or wetter or drier) than the surrounding climatic norms. The most pronounced producer of microclimates in most people’s gardens is their house – the sunny southern and western walls in particular can be markedly warmer than the rest of your yard. If you have hills, you also get frost pockets in low lying areas and warm south-facing hill sides.

But just how much warmer ARE your microclimates? I used to live in a drafty, poorly insulated nearly 100 year old house which had VERY warm microclimates all around it because all the heat my furnace put out was rapidly leaking out into the outside world. Great for growing plants that normally wouldn’t take my winters, but oh, the heating bills! A modern, well insulated house leaks a lot less heat out into the garden. Over time in a garden, you can learn by trial and error just how far you can push growing tender plants in warm microclimates by planting things and watching them die or survive. But there is an easier and faster way to figure out your microclimates. Collect some actual data, getting firm numbers of how warm and cold different parts of your yard are.

I’m heading into the first winter in a new garden, and getting ready to deploy a handful of cheap mechanical min-max thermometers. I’m placing one out in the open, the others against the south wall of a shed and other places I think should prove to be warm microclimates. Out they go, and after particularly cold weather – or just in the spring – I can check the different minimum temperatures they’ve recorded. A few degrees differences isn’t worth worrying about, but get to 10 degree differences, and you are talking a whole winter hardiness zone warmer.

In addition to comparing different locations in my garden, I also like to compare the actual temperatures I’m recording with those from local official weather stations (to do that, just go to www.weather.gov, enter your zip code, and then click “3 day history” on the right side of the screen). The zone map is created based on readings from weather stations like these, and if your particular yard is consistently showing temps warmer or colder than the local official readings (provided, of course, your thermometers are accurate), you should adjust your winter hardiness zone accordingly.

Finally, a min-max thermometer is a great way to test various winter protection methods. Tender plants can be insulated with a thick layer of leaves or (my favorite) cut conifer branches or even styrofoam boxes. How well do these protections work in your garden? Tuck a thermometer in with the plant before you cover it and then, come spring, check the minimum temperature it recorded against what you saw in the open air. Again, a difference of 10 degrees Fahrenheit corresponds to a whole winter hardiness zone warmer, giving you real actionable information about what you might be able to over-winter with the help of different sorts of insulation.

It is worth reiterating that minimum winter temperature is only one of a myriad of factors that go into winter hardiness, moisture, duration of cold, health of plants, and even summer heat matter as well, but winter lows are important, and it can be easily and precisely measured. So why not get some numbers on it so you can have a better idea of just what tender plants you can get away with in your various microclimates? A few thermometers is a lot cheaper than putting out a bunch of rare perennials and having them freeze out on you.