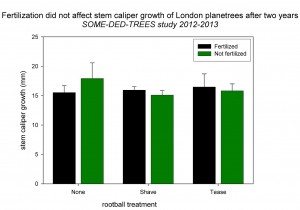

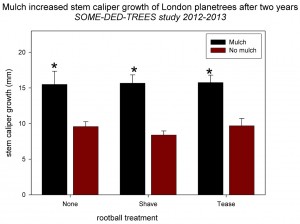

Linda and I are in Sacramento this week for the National eXtension Conference. I will be presenting later in the week on the work that we have done on the SOME-DED-TREES project. More on that in later posts. In the meantime, here are some photos from the State Capitol Park here in Sacramento. If you are ever in the area, I encourage you to check it out since the Park also doubles as an arboretum. The combination of mild winter temperatures and irrigation allows for as wide an array of trees as you are likely to see on one location. Many, but not all, of the trees have tags with common and scientific names. There are also numbered tags for a “Tree tour”. I have searched several sources for the tour map and came up empty. Judging by the condition of the tags and the number of missing tags, it looks like a forgotten project. If anyone has any insights, let me know. Or if you know an Eagle Scout in the Sacramento area, re-tagging and mapping would make a great project.

Palm tree tagged on the State Capitol Park Tree Tour

Italian stone pine Pinus pinea

Bark pattern (looked to be some type of Cuppressus but tag was missing

Lots of nice coast redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens)

Giant sequoia (Sequioadendron giganteum) as a street tree? These actually looked like they were doing well and then hit the wall. Note the fading top.

The park also includes a small rose garden and cactus garden.

You can hedge almost anything if you’re determined, even azaleas…

Just for Linda: Topiary at the hotel across the street.

Just for Linda: Topiary at the hotel across the street.