In my household, the weather is a common subject of conversation. That is only partly because I am married to a meteorologist. In fact, I have noticed that I can talk to almost anyone about the weather, and I suspect you can too. Weather is most captivating when something interesting is occurring, like liquid falling from the sky. When I give talks to master gardener groups, they are almost always consumed with how the weather is affecting their gardens. I get more questions about drought from these groups than almost any other topic, but rainfall, past or future, is also a frequent subject.

Today we will look at different types of precipitation, how they are formed, and how they affect garden plants. This is especially important as we move from summer, when rain is the most plentiful hydrometeor, into fall, when freezing rain, sleet, and snow become more frequent. Of course, this depends on where you are, and some Northern Hemisphere southern areas will experience almost no snow while for northern regions, it is the majority of what is observed.

What types of precipitation are there?

When I started writing my post, I looked online to see how many different types of precipitation were listed. I found that there is quite a variety in the number of types listed, ranging from two to seven varieties. I am going to lump them into two basic categories: liquid and frozen. But there are subcategories within these two basic buckets, especially in frozen precipitation, which includes snow, sleet, ice pellets or graupel, freezing rain, and hail. We will see how they are related to each other and yet distinct.

What is rain?

Rain is essentially liquid water that is falling from the sky and hitting the surface. If the air is dry enough, rain that develops in clouds evaporates before it gets to the ground, and that is called virga. Raindrops can form in tropical clouds through a liquid process that involves the collision and coalescence of small water droplets into larger drops that get heavy enough that they cannot remain suspended in the air and fall to the ground. But you might be surprised to know that most liquid rain starts as snow high up in the clouds, where the temperature higher up in the atmosphere is below freezing. We’ve addressed some characteristics of rain and how they affect gardens in previous posts here and here.

Clouds (except those in the deep tropics) are made up of a mix of supercooled water droplets and ice crystals that float around together, but it is easier for the ice crystals to grow by sucking up water vapor than for the water droplets to grow, so the ice crystals usually dominate the process of producing precipitation and snowflakes are the result. As these snowflakes fall towards the ground, they fall into warmer air near the surface and melt into the liquid water drops that make us wet. A light rain with small water droplets may be just a drizzle, but a thunderstorm with a cloud that is 10 miles deep could have water droplets as large as 0.34 inches, although I have heard unconfirmed stories about raindrops more than half an inch across in the heaviest rain events.

What types of frozen precipitation are there?

When precipitation freezes, it can take different forms depending on the temperature of the air that it falls through. If the air that the original snowflake falls through is below freezing through the entire depth of the atmosphere, then it remains as snow all the way to the ground. The shape of the snowflake depends on the combination of temperature and humidity that is present where the snowflake forms. They can take on an amazing variety of shapes beyond the typical dendrite that we usually associate with snow. The dendrites we often see falling in winter are ideal for blanketing the ground with a carpet of white, and their shapes make them able to trap a lot of air in the snow cover, providing insulation for the soil that keeps the temperature there relatively warm by protecting it from the cold and dry air the snow is falling through. In other words, it acts as a mulch to protect the ground and the plants there.

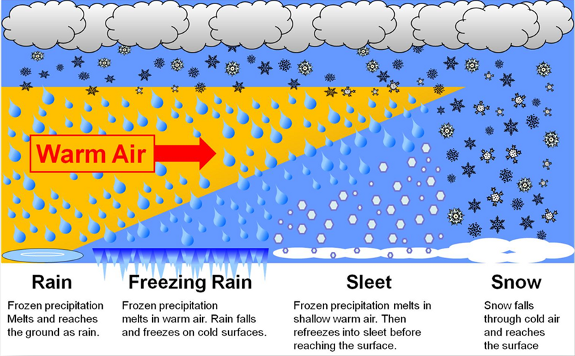

If the snowflakes from aloft fall through air that is above freezing, they transform from snowflakes to other kinds of precipitation, as shown in the diagram below. If the warm layer is deep, all of the snow changes back to liquid raindrops. If the air is above freezing but the surface is below freezing, then freezing rain occurs. The water sticks to trees, wires, and buildings, adding to their weight and collapsing them if the accumulations are thick enough. If the warm layer is relatively deep, but the air above the surface is below freezing, the water droplets may refreeze, leading to sleet or clear ice pellets. If the layer is thinner, the snowflakes may develop a coating of liquid water that surrounds the snow crystals from supercooled water in the clouds, encasing them in ice, leading to snow pellets or graupel, which are opaque instead of clear like sleet.

Hail is another variety of frozen precipitation that forms in summer thunderstorms, which can be as much as 10 miles high. In those storms, snowflakes can circulate vertically inside the storms due to strong updrafts, gathering a new coating of ice each time they move upward through the clouds, growing larger each time they cycle up and down. The largest hailstone ever measured was 8.0 inches in diameter and weighed 1.9375 pounds. It was discovered in Vivian, South Dakota on July 23, 2010. You will often find layers of clear and cloudy ice in hailstones as they travel up and down through the thunderstorms. Hail that is much smaller, as little as 0.25 inches, can cause damage to plants and crops as the hailstones shred leaves and cause damage to fruits and vegetables, leaving them unsightly and vulnerable to mold and pests.

How do different types of precipitation affect garden plants?

The most damaging types of precipitation for gardens are those that add weight to plants or cause impact damage when they hit something. Heavy snow and freezing rain can cause tree limbs to break due to increased weight, which trees cannot withstand, especially when they are still leaf-covered in fall or when they are not well maintained and have weak points in their structure. Garden plants can also be flattened or otherwise damaged by the heavy ice or snow cover. Previous advice in the Garden Professors by Linda indicates if the snow is really heavy, it should be removed from the plants before it can do damage, although lighter amounts can remain. On the other hand, snow cover on the ground can be a benefit to your garden if it incorporates enough air to serve as an insulating layer between the plants near the ground and the colder and drier air above it.

Hail, especially heavier stones, can cause significant damage to leaves and can defoliate gardens or farm fields completely in just a few minutes if the hail is intense enough. Even small hail can destroy tender plants, fruit, and flowers or at least damage the skin or leaves enough to decrease their value as crops due to cosmetic blemishes and places where diseases or insects can enter the plants. Gardens should be assessed for hail damage soon after a storm occurs, since the damage can be harder to spot over time.

How else can precipitation help gardeners with their gardens?

A previous post on GP noted that observing your garden after a heavy rain can be helpful in determining what the drainage patterns are and what might need to be addressed. While you might not be able to do much work in your garden right after a heavy rain event, it provides an excellent time to make future plans to make your garden more weather-proof.

Rain and snow, along with the other varieties of precipitation we experience, provide valuable moisture to our gardens as well as protection to plants in winter, but can also produce damage that can harm our garden plants. Enjoy the rain (or snow) when it comes, but be aware of the negative impacts it can have on your garden, too.