The hot weather that stimulated the last blog is still with us! Keep up the mulch and occasional watering to help shade trees. Today I want to cover a topic that seems like a garden myth but actually has considerable science behind it. Bicarbonate! The miracle cure for all garden pests? No. My wife came across an article in her news feed about a ‘garden guru’ who touted baking soda as a miracle cure for powdery mildew and other “blight” diseases. In this blog I will review the efficacy of the bicarbonate anion in disease control.

Bicarbonate as a disease control agent is not a new concept. Many studies going back a few decades documented the efficacy of this molecule in controlling foliar diseases of plants. Most studies are on powdery mildew of many crops and ornamental plants as well. Bicarbonate is typically available with three cations: ammonium, sodium and potassium. Most of the studies and efficacy are with the potassium salt of bicarbonate (not baking soda which is the sodium salt). All the salts are more or less efficacious against powdery mildew and a few other fungi like apple scab.

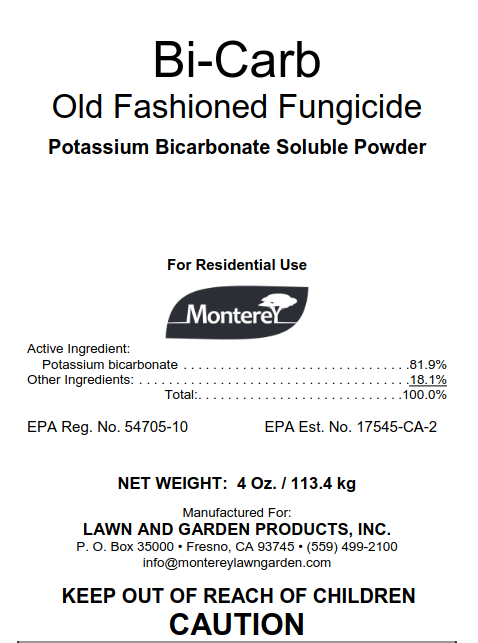

The mechanism of action of bicarbonate control of fungi is not clear, however Monterey Chemical that manufactures a Bicarb. product (Bi Carb Old Fashioned Fungicide) indicates on its label that the mechanism is the disruption of the potassium ion balance in the fungus cell, causing the cell walls to collapse

One frustrating thing with internet-based articles by garden “gurus” is that everything is some kind of “garden hack” Like we are getting something done on the sly or with common household materials. Using chemistry to control diseases is using pesticides. Companies test and approve these materials based on efficacy data as shown in the references at the end of this article. The benefit of using a registered product is that there are instructions that indicate how to spray, what the target organism is and the environmental conditions under which the product will work. Much of this is never mentioned in the “hack” articles.

Bicarbonate anion is an effective control of powdery mildew often as good as commercial fungicides with very different chemistries and methods of action. There does not appear to be resistance to bicarbonate. It is a contact fungicide (not systemic), the material must contact the fungus in order for it to work. In order to get good contact usually a wetting agent such as an ultrafine oil is combined with the tank spray solution to increase control.

It is best if bicarbonate is applied early in the disease cycle. Powdery mildew organisms are obligate biotrophic fungi. This means that the mildew fungus must grow in living plant cells. So when the mildew is killed the living plant cell is also killed. Powdery mildew is a disease of the epidermal tissues of plants so cell death is superficial but if late stage mildew is control by bicarbonates there can be phytotoxicity (plant damage) as most of the epidermal cells of leaves and flowers will collapse and die.

Powdery mildew fungi are in the Ascoymcete group of fungi and most have two spore stages. The first infections are caused by ascospores (sexual spores) that are released in the springtime. The primary infections develop and then asexual spores develop on plant surfaces that we recognize as powdery mildew. Stopping the primary infection by applying control early in the season will slow powdery mildew down on sensitive plants. Since many powdery mildews have broad host ranges they form on weeds an other plants and can move into protected plants later in the season. Frequent sprays will be required if conditions for the fungi are optimal and the spores are present. Bicarbonates do not have long-term protective effects since they work only when the solutions contact living fungus.

References

Zivand, O. and A. Hagiladi. 1993. Controlling powdery mildew in Euonymus with polymer coatings and bicarbonate solutions. HortSceince 28:134-126

Moyer, C., & Peres, N. A. (2008, December). Evaluation of biofungicides for control of powdery mildew of gerbera daisy. In Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 121: 389-394.

Holb, I.J. and S. Kunz. 2016. Integrated Control of Apple Scab and Powdery Mildew in an Organic Apple Orchard by Combining Potassium Carbonates with Wettable Sulfur, Pruning, and Cultivar Susceptibility. Plant Disease, 100(9), 1894-1905

El-Nogoumy, B. A., Salem, M. A., El-Kot, G. A., Hamden, S., Sehsah, M. D., Makhlouf, A. H., & Nehela, Y. 2022. Evaluation of the Impacts of Potassium Bicarbonate, Moringa oleifera Seed Extract, and Bacillus subtilis on Sugar Beet Powdery Mildew. Plants, 11(23), 3258.

Türkkan, M., Erper, İ., Eser, Ü., & Baltacı, A. 2018. Evaluation of inhibitory effect of some bicarbonate salts and fungicides against hazelnut powdery mildew. Gesunde Pflanzen, 70(1), 39-44.