One of the questions that arise in discussing native plants is the question of whether ornamental cultivars (e.g., ‘October golory’ red maple) can or should be considered ‘native’. In short, my answer is ‘No.’

Here’s my rationale on this. First, when we think about natives we need to put political boundaries out of minds and think about ecosystems. Political boundaries – a ‘Michigan native’ or ‘an Oregon native’ – are meaningless in a biological context. What’s important is what ecosystem the plant occurs in naturally. In addition to taking an ecological approach to defining natives we also need to consider its seed source or geographic origin. Why is it important to consider seed origin or ‘provenance’? Species that occur over broad geographic areas or even across relatively small areas with diverse environments can show tremendous amounts of intra-species variation. Sticking with red maple as an example, we know that red maples from the southern end of the range are different from the northern end of the range. How are they different? Lots of ways; growth rate, frost hardiness, drought tolerance, date of bud break and bud set. Provenances can even vary in insect and disease resistance.

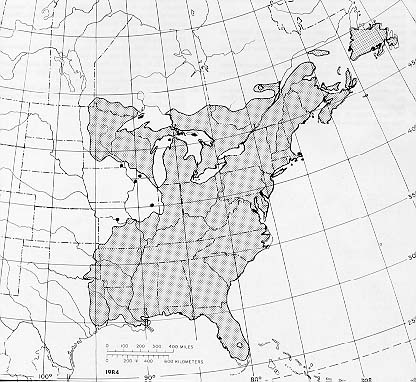

Native range of red maple

If we’re dealing with an ornamental cultivar, do we know the original seed source or provenance? Sometimes yes, sometimes no, sometimes maybe. Think for a minute how most ornamental cultivars come to be. Some are developed through intentional crosses in breeding programs. The breeder may or may not know the geographic origins of the plants with which they are working. Or they may produce interspecfic hybrids of species that would not cross in nature. Some cultivars are identified by chance selection; an alert plantsperson finds a tree with an interesting trait (great fall color) in the woods or at an arboretum. They collect scion wood, propagate the trees and try them out to see if they are true to type. If the original find was in a native woodlot and the plantsperson kept some records, we may know the seed source. If the tree was discovered in a secondary location, such as an arboretum, it may not be possible to know the origin.

So, if a breeder works with trees of known origin or a plantsperson develops a cultivar from a chance find in a known location AND the plants are planted back in a similar ecosystem in that geographic area, we can consider them native, right? As Lee Corso would say, “Not so fast, my friend.” We still need to consider that matter of propagation. Most tree and shrub cultivars are partly or entirely clonal. Cultivars that are produced from rooting cuttings; for example, many arborvitae, are entirely clonal. Cultivars that are produced by grafting, like most shade trees, are clonal from the graft union up. The absolute genetic uniformity that comes from clonal material is great for maintaining the ornamental trait of interest but does next to nothing to promote genetic diversity within the species. From my ultra-conservative, highly forestry-centric perspective, the only way to consider a plant truly native, it needs to be propagated from seed and planted in an ecosystem in the geographic region from which it evolved. Few, if any, cultivars can meet that test.