Like many people we spent the past couple days digging out from the massive snowstorm that swept across a large swath of the country. This was definitely a made-for-TV-weather event as national and local TV weatherfolks took up their positions and gave us breathless live-remotes of the “Blizzard of 2011”.

40 mph wind + 1 little crack = a barn full of snow.

Almost as predictable as video footage of snow-ploughs on the streets and locals snow-blowing sidewalks; climate change skeptics are using the recent round of winter weather as proof that global warming is a hoax and that there’s really nothing to worry about except the economics of ‘cap and trade’. Just google “climate change skeptics blizzard” and you’ll get the idea.

Bob and Quincy were unfazed by the sub-zero wind-chills.

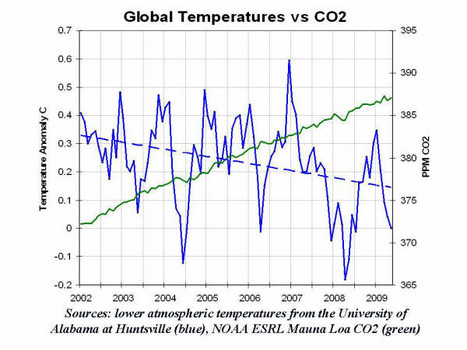

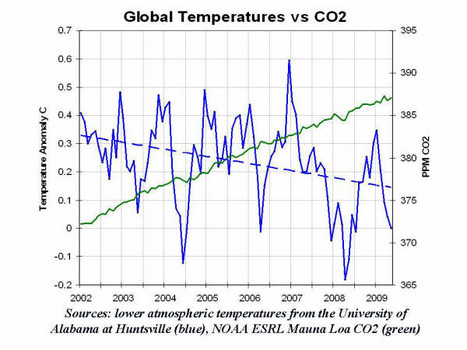

The problem, of course, is that climate patterns don’t move in a strictly linear trajectory and looking at one extreme event doesn’t prove anything one way or the other. Even looking a few years time sequence may not present the full picture. Deroy Murdock used the illustration below to argue in the National Review Online that there is no link between rising CO2 and increasing temperatures.

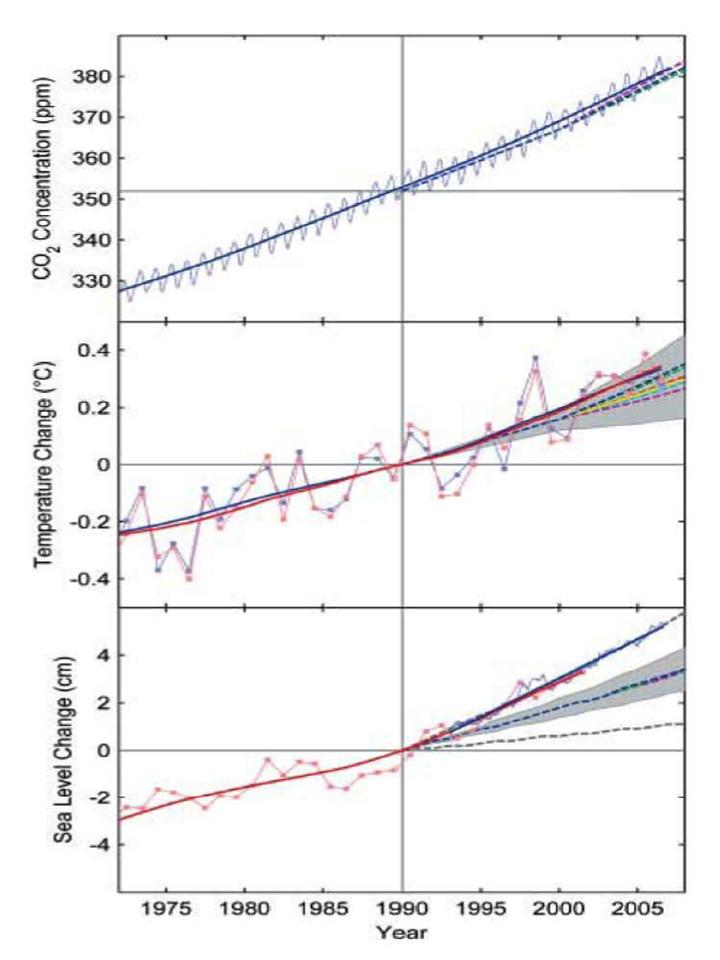

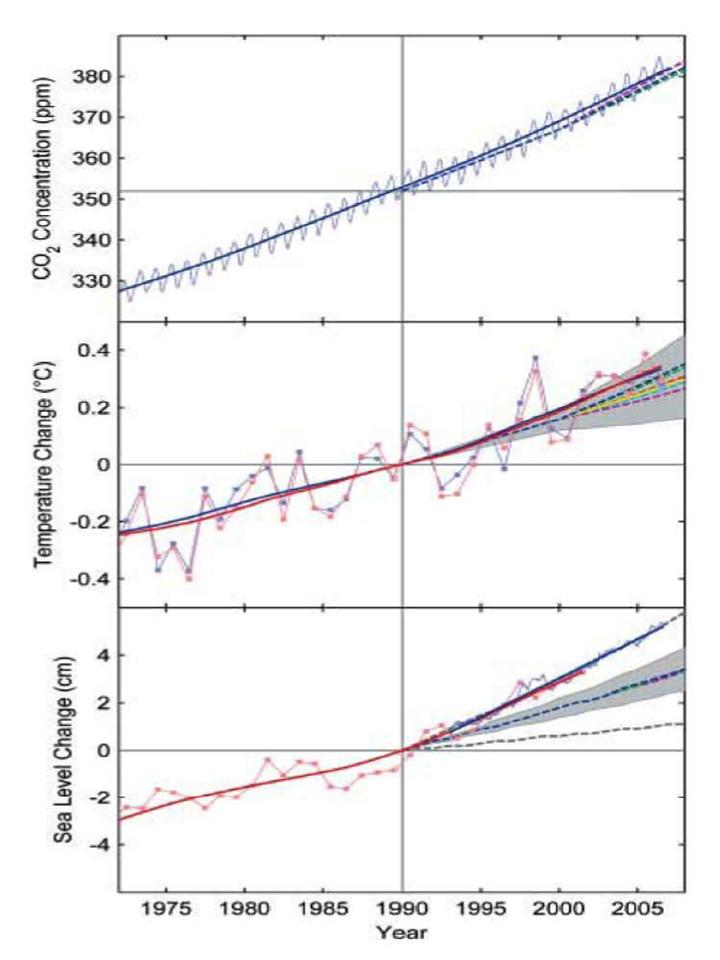

But looking at a broader timescale tells a different story. While there are year to year fluctuations a clearer association between rising CO2 and global temperature begins to emerge.

The figure above was taken from an article by Stamhoff et al. 2007, “Recent Climate Observations Compared to Projections” (Science 316 (4): 709). The dashed lines represent the ranges predicted by a major climate model starting in 1990 – the solid line represents what actually happened. As shown in the figure, climate models have been fairly accurate overall and, if anything, have been conservative in predicting climate change; especially with regard to changes in sea level.

So where am I going with this? There are certainly enough climate change debate/Al Gore bashing blogs out there to go around and I don’t want to devolve entirely into that debate, but the simplistic ‘exception proves the rule’ mentality of the skeptics gets a little tiresome. I remember hearing my first talk on global warming at a forest biology conference in the mid-1980’s. The main point that stuck with me then was that increasing global CO2 would not necessarily result in warming every year but that we would see an increase in the frequency and severity of extreme climatic events; droughts, hurricanes, floods, and yes, even blizzards. Even some of the earliest discussions on climate change in the early 1980’s (e.g., Manabe and Stoufer 1980) recognized complex feedbacks in the global climate system that would result in some regions getting wetter while others suffered drought. So while the skeptics may use this weeks’ blizzard as evidence against climate change, increasing frequency of severe weather actually argues for it.

A few other climate facts to ponder:

-Global CO2 is increasing and continues to increase (see top panel in figure above).

– Globally, 12 of the 13 warmest years on record have occurred since 1995.

-Intensity of hurricanes and cyclones is increasing (Webster et al., 2005). While Fox and Friends were happily using the Blizzard of 2011 to debunk climate change; did they notice the most powerful cyclone on record was slamming into Australia?

-Frequency and severity of droughts is increasing worldwide (Burke and Brown, 2006).

-Glaciers are disappearing. If you want to go to Glacier National Park and actually see a glacier, you need to hurry. In 1850 there were 150 glaciers in the park. Today there are 25 and they will likely be gone in 10 years.