Much as I am itching to continue the current discussion on cultivars of native plants, I’ve got to wait until next week (my seminar schedule has me hammered – doing my third one this week tomorrow). So instead I thought I’d throw out some suggestions for those nonscientists who blog and/or write about all things planted.

First of all, I do enjoy reading blogs, articles and books by nonscientists who venture into plant and soil sciences. But there are common errors that both interrupt the flow and – fairly or unfairly – can cause me to question the writer’s grasp of the subject matter. Here are some of them in no particular order:

Nomenclature:

1) Common names are not capitalized unless they contain a proper noun. (This is a general taxonomic rule for plants – and sorry, I didn’t write the rules!)

2) Scientific names are always italicized or underlined; the first letter of the genus is capitalized, the species name is usually not. (Also, they’re not “Latin names” – many scientific names actually come from Greek roots.)

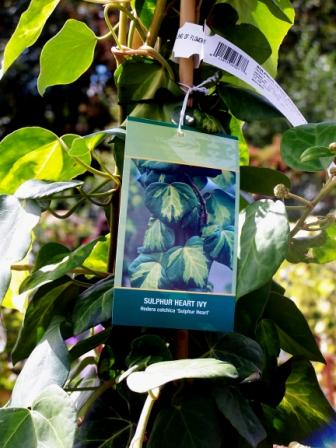

3) While we’re on scientific names and in a nod to our discussion of cultivars, let’s address that one too. When a scientific name is followed by a cultivar name, the cultivar name is either preceded by cv., or is set off in single quotes. The cultivar name is capitalized. So this is how the weeping blue atlas cedar would appear: Cedrus atlantica ‘Glauca Pendula’ or Cedrus atlantica cv. Glauca Pendula.

4) Plant family names always end in -aceae, which literally means “family.” When someone writes “the Asteraceae family” they are being redundant. (This always reminds me of a scene from Mickey Blue Eyes, where the characters are discussing a restaurant called “The La Trattoria” – which, of course, translates to “the the restaurant.”)

Scientific information:

1) The word “data” is a plural noun (datum is the singular form). Therefore, “data” must take plural verbs.

2) “Proving” that a product or practice works. The philosophy behind the scientific method states that one can never definitively “prove” anything. Thus, we can have results that support a hypothesis, or we can disprove it. (Yes, marketers do this, but garden writers shouldn’t.)

Terminology:

1) “Pesticide” is a generic word that means “pest killer”. Herbicides kill plants, fungicides kill fungi, and so on. Many nonscientists incorrectly think that pesticide means the same thing as insecticide. It does not.

2) Flowers and fruits are reproductive structures of angiosperms (the flowering plants). Conifers do not have flowers, nor do they have fruits; their seeds are born on cones. Many scientists, as well as nonscientists, incorrectly label the cones of Ginkgo and Taxus (yew) as fruits.

I’m sure my GP colleagues can come up with some other ones, and maybe you can as well. Comment away!