Today I was sent a link to a posting on “droopy leaves.” Essentially, it suggests that droopy leaves are a means to conserve water on hot days and that watering these plants causes more problems than it solves because the roots don’t get enough oxygen. A link to the science of transpiration is provided. The advice is to wait until the evening and if the plants perk back up, then they didn’t need water after all.

This is one of those maddening articles that has enough science in it to make it sound reasonable, but is ultimately incorrect in its assumptions and advice. It’s worth looking at the topic in a little more detail.

Some plants are adept at conserving water in hot weather. Their leaves tend to be small, thick, with a heavy layer of waxes protecting the surface. Leaves can also move to limit their sun exposure and thus reduce the heat load. But wilting is not a method of conserving water. Instead, it’s a sign that water loss (evapotranspiration through the leaves) exceeds water uptake from the roots. And if you ignore wilt, you do so at your own peril. Once terminal wilt is reached, it’s all over for that part of the plant.

Wilt. Sorry it’s a fuzzy photo.

Large, thin leaves, common in many of ornamental, annual and vegetable species, do not conserve water. Tomatoes, zucchini and black-eyed susans, the plants specifically mentioned in this article, are not water conservers. Chronic wilting of these and other can eventually cause leaf tip and margin necrosis (or tissue death). It also reduces growth, so that your yield of tomatoes, zucchini and black-eyed susans will be decreased.

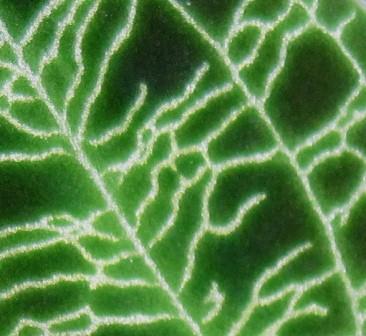

Leaf tip and marginal necrosis from chronic drought stress

Leaf tip and marginal necrosis from chronic drought stress

So yes, do water your plants if they are wilting in the midday heat! Use mulches to conserve water! (You’ll notice in the photograph on the linked site that the plants are in bare soil.) Fine root systems are generally near the soil surface, and keeping these hydrated keeps them alive. You won’t see an instantaneous response to watering if plants are already wilting, but they will recover – much better than if you don’t water them at all.