Too easy! Yes, Friday’s evil grin photo was on a head of cabbage (taken on location for this week’s podcast to be posted tomorrow. So yes, Robin, this is YOUR cabbage!).

I especially liked the more “creative” answers – you guys are fun!

We typically think of mulching landscape beds as a good thing. And it usually is; helping to conserve soil moisture, reducing soil temperatures and contributing to soil organic matter. Recently, however, I received an e-mail from a local landscaper that reported severe damage to annuals and perennials in a landscape bed immediately after applying hardwood mulch. The problem, sometimes referred to as ‘sour mulch’ or ‘toxic mulch’, occurs when mulch is left is large piles and undergoes anaerobic conditions. This results in the production of acids and other compounds that can volatilize when the mulch is placed in beds, especially during hot weather. These vapors can quickly damage annuals and other sensitive plants. Mulch in this condition is often characterized by a ‘sour’ smell. If you suspect your mulch has gone sour, spread it out before use to allow toxins to dissipate and water thoroughly either before or immediately after application. The University of Arkansas Extension has a nice fact sheet in the subject “Plant injury from ‘sour’ wood mulch.http://www.uaex.edu/Other_Areas/publications/PDF/FSA-6138.pdf

Fried Gerber daisy

Sedums are usually pretty tough…

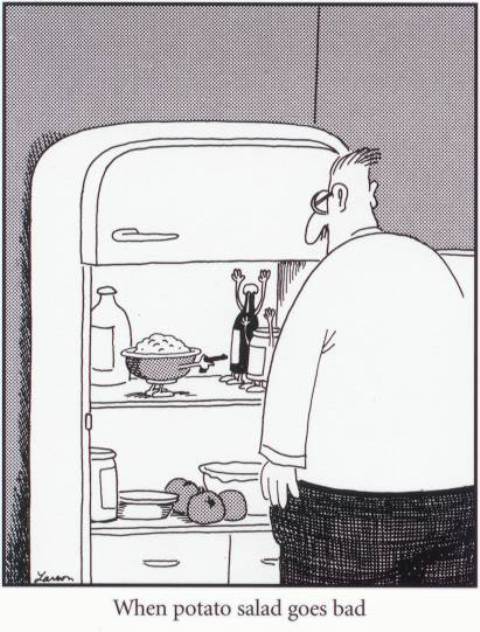

And, yes, I did steal the title of this post from one of my all-time favorite ‘Far Sides’…

Is this title too extreme? I’ll leave that up to you.

Most of you are aware of the frog controversy that surrounds Round-up. A few years ago a professor from Pittsburgh showed that this chemical can kill aquatic creatures if it gets into a pond. Particularly tadpoles. Not that Round-up is intended to be used around water, but still, it is a concern and I don’t want to minimize it. Nor do I want people to forget that other supposedly safer products have their own set of dangers.

This past Sunday I was in the back yard pulling weeds (there is the possibility that my post last week led to this fate…but I’m not going to examine that here). One of the places where I pulled weeds was under the deck at the back of our house. This area is covered with rock mulch and hasn’t been weeded all year. I started out pulling the large weeds, which took about 15 minutes, and then I started pulling the smaller weeds. After another 15 minutes I realized there was no way that I was going to be able to pull all of the small weeds in what I considered a reasonable time. So I went to the garage where I found a bottle of 20% acetic acid – that super strong weed killing vinegar spray that I’ve mentioned before. I knew the stuff was too strong and not a great choice — I had been planning to take it in to school and use it for some experiments there, but I figured what the heck, it ought to do some damage to the little weeds, even if it doesn’t completely wipe them out. So I started spraying.

The first things I noticed were things that I’ve had to cope with before when using this trigger-spray bottle. The spray misted onto my hand and hit a small cut making further spraying uncomfortable – but I pressed on (At this point you should all be screaming at me PUT SOME DAMN GLOVES ON – You’re right this was a stupid move on my part) and the smell was almost overwhelming. But I expected these things, so I figured I’d finish. Then, out of the corner of my eye I saw something coming from an area that I’d just sprayed — moving across the gravel and approaching fast. It was a small toad, no doubt there to eat slugs. He was hopping all over the place with no apparent direction. Random leaps here and there. I picked him up – and noticed that his eyes were glazed. I called for my wife to bring a bowl of water – which she did. I washed him off, but he had already stopped moving. A few minutes later it was no better – just random twitches and nothing else. His eyes seemed covered by a fine film – almost like cataracts. I put him in a cool moist shady spot hoping that he might get better, but I didn’t have the heart to check on him. The vinegar did him in.

I kill insects and other critters all the time and I’m no vegetarian — so why should I whine about this little guy? Because it’s always a shame when a life is lost without a purpose. This guy was helping me out underneath that deck and I killed him because I made a stupid decision by using a pesticide which I knew was a bad choice. If I’d used Round-up (which I have accidentally sprayed a small amount of on adult toads without apparent effect)– or better yet taken the time to pull the weeds by hand I would have avoided this whole situation and I could have done a better job killing the weeds too.

Okay, so it’s actually Thursday morning. We’re doing a "staycation" this week and my farm work to-do list dwarfs my usual work week. Not exactly relaxing. One of the daily duties is dragging the hose around trying to keep some favorite plants alive. We’re in a drought, though not near of the awful and epic proportions of some parts of the country. When our Floriculture Forum was held at the Dallas Arboretum this spring, horticulturist Jimmy Turner welcomed us to "Gardening Hell." Huh? Everything was lovely, verdant, and smothered in tulips. But that was February. Bless all your gardening hearts out there (and everywhere else that is so damned dry).

I do get to drag the hose right past one of my favorite garden additions of the last few years. Bulbine frutescens is a South African native that thrives in dry, dry, dry. USDA Zone 9 or thereabouts on the ol’ hardiness scale. We’ve planted it in our tiny scree garden, where several succulents get to spend the warm season stretching their roots before getting scooped back into a pot to overwinter in a chilly greenhouse. (And pardon if Bulbine is as common as mud in your part of the world/continent, it’s just not that well known in the eastern part of the U.S.)

Bulbine frutescens ‘Hallmark’. Looks a bit like my hair this morning. Yes, it would benefit from some deadheading (the plant, that is).

Bulbine foliage looks a lot like the "grassy" species of aloe, and the juice from the leaves is supposed to have some of the same properties when applied to burns and scrapes. It has a fairly neat habit, but within the mound of foliage forms lots of rhizomatous clumps. These are perfect for dividing and sharing (despite the genus name, no bulbs are involved). It flowers non-stop, even throughout most of the winter in the 50 F greenhouse. Our plant is the orange cultivar ‘Hallmark’. The straight species has yellow flowers and can reseed a bit; but I’ve never seen a seedling.

Lovely flowers. No extra water needed – yay!

I’m getting my feet under me with podcasting – it’s becoming more fun and less scary. The theme for this one is “Garden Concoctions,” so the Plants in the News and Myth Busting segments are along those lines.

My interview this week is with Maurice Skagen, owner and designer of Soos Creek Botanical Gardens. This 23 acre plant collection has been carefully cultivated over the last 30 years and just recently opened to the public.

A volunteer visits with Maurice

Soos Creek draws visitors of all ages

The pond

The long borders

Clematis canopy over trees

Demonstration vegetable garden

Please let me know what you think of the podcast; you can email me directly or post a comment on the blog. Suggestions for future podcasts are most welcome!

A recent NYT post reports that adding fish meal to lead-contaminated soils will cause the lead to bind to phosphate found in fish bones. As the article explains, this chemical reaction results in the formation of pyromorphite, “a crystalline mineral that will not harm anyone even if consumed.”

Given my concerns about excessive phosphate loading in urban soils, I contacted Dr. Rich Koenig, an urban soil scientist and chair of WSU’s Crop and Soil Science department. I wondered, at least, if the article should have directed people to have a soil test done first to determine how much phosphate was already in the soil before adding more.

Dr. Koenig was likewise concerned that the application rate of fish meal was probably far higher than what plants would require, thus increasing the risk of phosphorus leaching and runoff. He also referred my question to Dr. Jim Harsh, a soil chemist in his department familiar with the process described in the article.

And as Dr. Harsh pointed out, it’s important to make lead less susceptible to uptake by people and other animals exposed to contaminated soils. However, he’s unconvinced that phosphate is the best choice; in fact, research by Dr. Sally Brown (cited in the NYT article) and others (including Dr. Harsh) have found that compost containing iron is also able to bind and immobilize lead. The advantage of high iron compost is that iron will not leach into nearby waterways, nor cause the same kinds of plant toxicity problems, as phosphate can.

Thanks to both Dr. Koenig and Dr. Harsh for their quick and informative responses on this topic.