Over the last couple of months I started a series on raised bed gardens, focusing on materials and preparation. In this final installment, I’ll focus on maintenance activities to avoid in your raised bed systems and remind you of three things you should always do.

Terrible traditions

We’ll start with some practices that damage soil structure and function (GP John Porter discussed this in much detail a few years ago). Tilling, once the mainstay of soil preparation for crops, is increasingly found to cause more damage than good. Grinding the soil into a material with the texture of coffee grounds might look pretty, but it’s devoid of the ped structure that allows water and gas to move through easily. It also increases microbial activity by bringing up microbial spores, which release carbon dioxide to the atmosphere as they digest whatever organic material is there. And tilling will increase the likelihood of erosion and compaction.

This is the opposite of what gardeners should want: an optimal soil has natural structure which might look messy but allows for good drainage. It’s also more resistant to compaction and erosion, especially when it’s protected with mulch (more on this later).

Speaking of drainage, don’t be tempted to add gravel or some other coarse material at the bottom of the bed. The change in soil texture creates a perched water table, which makes for a soggy planting bed and optimal conditions for soil-borne diseases.

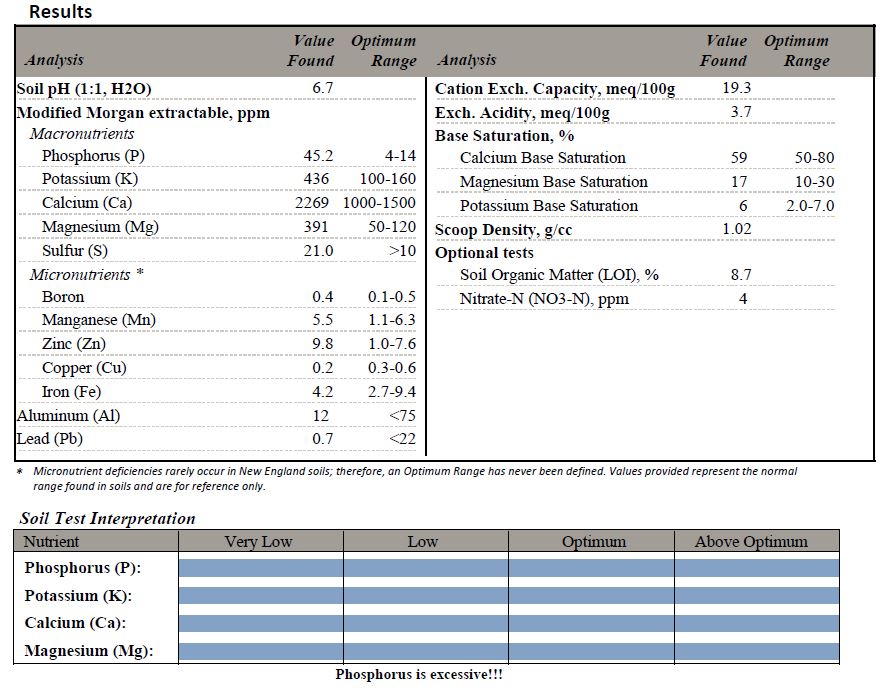

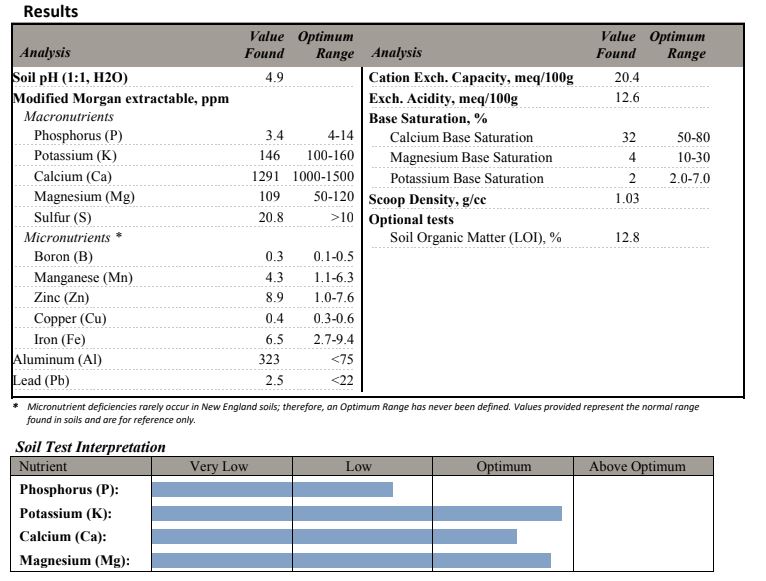

While we’re talking about unnecessary or harmful additions to your raised beds, let’s not forget the annual addition of compost or other rich organic material. This is a holdover from old agricultural practices and is not warranted unless you have an organic material deficiency. Without a soil test, you don’t have a clue about what your soil has or what it needs. The problems associated with routine amendments are discussed in this peer-reviewed fact sheet, and are exacerbated by the tillage that is often the means to incorporate compost. Likewise, don’t add fertilizers and pesticides unless you have conclusively identified nutrient deficiencies or pest issues.

The last tradition I’d like to see shelved is growing cover crops. This practice originated in the management of agricultural fields, which were otherwise left bare after harvest. Outside of producing some kale or other winter vegetables, what’s the point of planting a cover crop in your garden, when you can protect the soil in other ways? Cover crops require water and nutrients, which eventually will need to be pulled or incorporated. You are forcing your soil system to continue to support plant growth and be subjected to disturbance with the planting and harvesting of the cover crop. Why not let the soil rest over the winter with a nice blanket of mulch? Give it a chance to regenerate its nutrient load while being protected from unnecessary disturbance.

Three tips

Two of these tips have been discussed many times in this forum, so I’ll direct you to longer discussions of soil testing and mulching. Mulching is not just important for protecting the soil bed after the growing season, but should be used on actively producing beds. A deep, coarse organic mulch will promote water and air movement, moderate soil temperatures, reduce weeds, and provide a slow feed of nutrients throughout the season. You’ll have to wait until your seeds are up to apply it, of course, but try to avoid bare soil as much as possible.

Soil testing is really crucial for any garden, but perhaps most important in vegetable gardens where harvesting may decrease key nutrients over time. It will also guide you in identifying potential heavy metal problems. The money you will save in not buying unnecessary fertilizers and other amendments will pay for many soil tests.

Sometimes you will need to add material to your existing beds if you are not using a natural soil. Soilless media (deceptively marketed as “potting soil” though no soil is to be found) will decompose and settle over time, leaving you with a sunken soil system. You will need to add more of the same sort of media to the beds, making sure you mix it in thoroughly to prevent a perched water table. (This is why you might consider using a natural soil and avoiding this annual chore – because a natural soil will not subside over time.)

Trying to figure out how to subscribe to your blog…. and hope this works, because I love it! — from a librarian/gardener in Ithaca NY

Good question! We used to have an RSS feed button, but now we have a subscription box. Go to the bottom of the left hand menu and you’ll see it there.

The RSS feed is still there: http://gardenprofessors.com/feed/

I can’t open this, but I will believe you!

The orange bag of planting medium you pictured in your article reminded me of a product I used while living in the Sacramento Area . What is the name of this supplement and who makes it?

Sorry, I cropped the brand name out on purpose. My main point was to show that “potting soil” has no soil in it.

It is a great idea to have raised beds for small plants. Especially, when the natural soil in your home don’t support plants. Soil less media is new and I am yet to try. It sounds easy as per your experience but I am going to have tough time. Bit of a lazy gardener.

What do you think of coconut coir ?, I have been using it in my raised garden beds mixed with potting soil and fertilizer.

There has been quite a bit of research on using coconut coir as part of a potting mix, and I personally use it in my carnivorous plant container rather than peat moss. Other than that, I haven’t used it as our native soil is a perfect mediun to use and doesn’t have to be replaced.